More than 47,000 people, 9,700 ships and 127 planes spent months cleaning up oil released during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Yet, four years later the tools to fight offshore oil spills remain remarkably rudimentary. Now a team of University of Rhode Island engineering professors is demonstrating novel approaches that could change the way we battle oil spills.

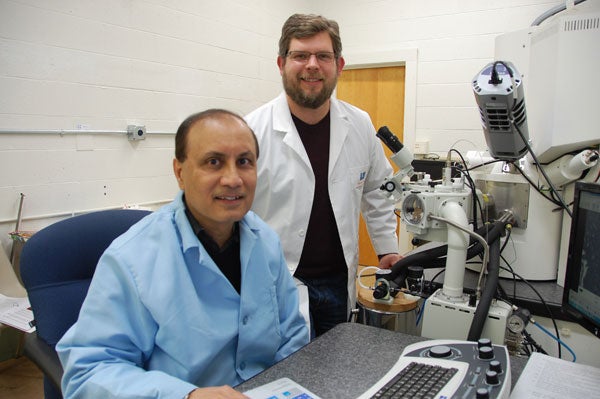

Led by chemical engineering Professors Arijit Bose and Geoffrey Bothun, the approach relies on nanoparticles each about a hundred times thinner than a strand of human hair. To study how these tiny particles can clean up oil, the professors have received $995,775 from the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative established in wake of the Deepwater Horizon disaster. Since their funding arrived in 2011, Bose, Bothun and their collaborators have published their results and small-scale pilot projects are now being explored to evaluate the potential for commercialization.

“On the downside the Deepwater Horizon spill happened,” Bothun says. “On the upside it motivated a lot of engineers and scientists to come up with new ways to fight oil spills.”

At URI, Bothun and Bose are taking complementary approaches to stop oil from forming globs that threaten wildlife and wash up on beaches. To emulsify the oil (break it into small droplets) and make it attractive to oil-eating microorganisms, Bothun has turned to silica and Bose to carbon black.

To investigate the ideas, the professors formed an interdisciplinary team that crosses departments and universities. URI civil and environmental engineering Assistant Professor Vinka Oyanedel-Craver is working with Bothun. Chemistry Assistant Professor Mindy Levine and Metcalf Institute Executive Director Sunshine Menezes are partnering with Bose. Researchers at Brown University and the University of Florida at Gainesville, along with students from URI and other institutions, round out the team.

Bothun’s research seeks to turn off-the-shelf products into oil spill cleaners. Currently, responders often rely on chemical dispersants, which are effective but their safety is questioned. So Bothun and his team of students turned to nanoparticles of benign silica (sand) and FDA-approved surfactants, which force oil to emulsify.

Teaming up with researchers at the University of Maryland and Texas A&M International University, Bothun’s group found that some nanoparticles and surfactants work very well alone or in combination with traditional dispersants. The team hopes that when loaded with nutrients, the compounds stop oil from forming slicks on the surface of the ocean and attract microorganisms that eat oil.

Down the hall, Bose and his team want to turn carbon black into the go-to dispersant. Generally considered safe, the particles emulsify oil, absorb toxic polycyclic-aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), are widely available and are inexpensive.

Bose started researching the potential of carbon black to clean up oil while on sabbatical at Cabot Corp., one of the world’s largest producers of carbon black. In collaboration with researchers there and at Tulane University, Bose discovered carbon black is a powerful oil emulsifier.

“Nobody has used carbon black in this way,” Bose says. “It seemed like a good idea because it’s so widely available.”

The professors say both their approaches could be tweaked to assist with oil spills occurring in extremely cold water. That potential has taken on new urgency as oil companies express interest in drilling in the Arctic.

“The Gulf of Mexico spill that started this research was just one spill,” Bothun says. “Other spills are going to happen. Whether they’re close to us or not, we’re going to have to come up with ways to minimize the damage.”