More Global Go-Betweens

The Peace Corps, as Dave Lavallee writes in “Global Go-Betweens” (QuadAngles, Summer 2017), is made up of “thousands, maybe millions of intensely personal, undeniably tangible” stories from individuals whose lives were changed by serving through the Corps. So many stories, in fact, that when Dave set out to capture a snapshot of our Rhody connection to the Peace Corps, he couldn’t fit them all in the print magazine. Here, then, are more of these incredible stories.

If you’d like to share your story, please use the comments section at the bottom of this post to tell us about your experience with the Peace Corps.

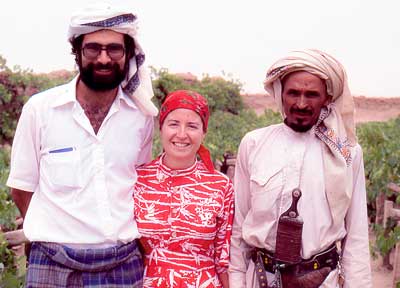

Yemen 1978

Anne and Ed Stulik, both class of 1976

You were newlyweds in 1978 when you joined the Peace Corps. Was it something you discussed as undergrads?

AS: We had always been interested in traveling and had considered other volunteer organizations. We were accepted by the Peace Corps four months after our marriage.

What inspired you to join?

AS: We wanted to fulfill President Kennedy’s wish for the Peace Corps to bridge understanding throughout the world.

ES: I received my B.S. in zoology from URI, but with an eye to the health field as a career. I looked into overseas volunteering as a way to get some hands-on experience and see if health care was something I wanted to do.

Did you serve in the same place in Yemen?

AS: The Peace Corps mandated that married couples serve together. Yemen is a patriarchal society and we fit right in being married. The single volunteers had a little more trouble getting accepted.

Please share some memories and challenges.

ES: We never felt in danger or threatened by Yemenis. The biggest threats to our health were MVAs and dysentery. The people were very hospitable—when traveling around the country on weekends off, the people would always insist that you stop, have tea and talk. They were very curious about us. A big challenge for me as a vaccinator was convincing the locals to have their tiny infants stuck with these big needles to immunize against disease. The concept of immunization was difficult to get across in Arabic, and the kids would usually get sick for a few days from the vaccine. A successful vaccine series was three sets. Only about 20 percent finished all three.

Did the Peace Corps influence your careers and family life?

AS: I was already an RN when I went into the Peace Corps, but due to my experience there as a midwife, I went on to graduate school and became an OB/GYN nurse practitioner, presently working at Women and Infants Hospital.

Ed’s Peace Corps experience working in the clinic and assisting in the OR confirmed his decision to become a physician and he applied to medical school on his return.

ES: It helped point me towards a career in medicine, but also gave me a better understanding of people, culture and the importance of respecting every individual.

Have you been back?

AS: Due to safety concerns, we have not been able to return to Yemen. We keep in touch with other volunteers, attend reunions and have access to Yemen’s newspaper.

Dominican Republic 1963

Rwanda 2017

Caroline Burns ’15

What inspired you to serve?

I wanted to find the best way to use my URI education while also doing things I’m passionate about, like traveling. Peace Corps just seemed like a fantastic mixture of those two things.

An advisor here was discussing why we should be serving overseas while there are so many people we could help in our own country. He quoted something to this effect: You must serve where the need is greatest and where you can make the most change. I think of this when I want to be back home where I’m comfortable and with my family. I know I’m in the right place doing the right thing. Serving others is about yourself just as much as it is about the people you are serving. While giving my time and knowledge to others, I become happy. Then, because I am happy and fulfilled, I can continue to serve others to the best of my ability. It’s a cycle.

What has been the best part of of your experience so far?

The people are my favorite part so far, Rwandans and Americans alike. All of the Rwandans I’ve met have been so kind. Many have taken me in like a family member. People go out of their way to make sure you are happy and okay. My new American friends are my support system. Without them, I wouldn’t have been able to transition to a life where nothing is familiar. They are my rock.

I am starting to love living in a different culture. Whenever I learn something new (which is every single day), I feel so fulfilled, so accomplished. Being out of the United States has become a non-issue—except for when I’m really hungry. I also feel like it is changing me as a person, in ways I can’t even identify yet. One thing is for sure: I feel as though I could do anything after doing this.

What has been the most difficult part of the experience?

It was the first month at my village without another American (or non-Rwandan) for miles. As soon as my advisor drove away, I could feel the tears welling up. It was shocking. I wasn’t afraid. It was a deep, deep feeling I didn’t really understand. During training, I was constantly with other Americans. I was barely homesick. When I got to my village and started living alone, it became so hard.

After a month or so, I became used to my village and its people. My language was better and I knew some people’s names. I had my favorite little stores to go to to buy eggs and toilet paper and other essentials.

What I learned from this was that it is okay to be alone. I learned that I won’t just wither and crumble up without talking to someone who’s familiar to me (though, in that first month, it felt like I would). Basically, I learned that I could overcome that loneliness and that it couldn’t control me. It was one of the hardest lessons I’ve learned in my life.

Will your Peace Corps experience have any effect on your nursing career?

I absolutely think so. I pursued the maternal child health program with the Peace Corps because it was the subject I most enjoyed in my URI courses. Being here has opened up so many doors of possibility: research nursing, HIV/AIDS prevention, travel nursing, malnutrition intervention. It will be hard to choose when I am home.

Did URI provide you with a foundation for Corps success?

Rigorous as it was, the URI Nursing program provided me with much needed knowledge on topics I am involved with every day here. I think I am more successful here because of how rigorous the program was.

One individual that inspired me to follow an international path was Ginette Ferszt. She was my professor for psychiatric nursing, and she also has a passion for travel. She has gone to many different places as a nurse—Iceland and Cambodia come to mind, though I’m sure she’s been many other places. She showed me that I didn’t have to put my nursing career on hold if I wanted to travel. Though she may not know it, she really inspired and encouraged me to join Peace Corps. I consider her not only a professor, but also a good friend.

Kenya 1974

Kate O’Malley ’73

Nursing major Kate O’Malley ’73 was sitting in her residence hall in 1972 watching the Olympic Games on a 9-inch, black-and-white TV when she saw the story of Kenyan gold medalist Kip Keino.

“I still remember it all very clearly—Kip Keino running through the hills barefoot,” O’Malley said. “I thought, ‘This would be an awesome place to go,’ and that ‘the Peace Corps goes to Kenya. I can join the Peace Corps and that’s how I can go.’”

The Peace Corps assigned her to a medical education group consisting of two pharmacists, two occupational therapists, a medical technician, four nurses and one doctor. After training for classroom teaching and basic language skills in Swahili, group members were posted to provincial medical education centers across the country. O’Malley went to the Western Province.

“When I arrived in Kakagega, I took over from a nurse from New York, and she said, ‘Of course, you have to hire Alfred as your house boy. This is his job, and his family depends on his salary. He will live in the servant’s quarters.’”

So, as a 23-year-old from a lower middle class family, she found it strange to hire a servant, but paid him $25 a month to help support his family and the local economy. He did her food shopping at the local market and other household duties like cooking.

She came to enjoy her work so much that she extended her contract and moved to Nairobi, where she worked for the Ministry of Health to change the national nursing curriculum. After that, she became a trainer for newly arriving Peace Corps Volunteers.

For a girl who went to school in the Blackstone Valley and worked on the assembly line at Hasbro when it made toys in Rhode Island, this was life-changing.

“The Peace Corps experience was how I could take my professional education and do something that demonstrated I was an adult,” O’Malley said. “I loved living in a foreign country, speaking a language unfamiliar to most and learning how to be a teacher.”

O’Malley completed her professional career in February 2017, retiring as a senior program officer for the California Healthcare Foundation, a philanthropy focused on care for safety net populations in California. In that role, she managed the foundation’s grants to promote appropriate care toward the end of life.

“When I was in Kenya, I worked in a rural health training program that prepared health care staff to deliver interdisciplinary, team-based care,” O’Malley said. “I learned interdisciplinary team care is efficient, effective and self-supporting.”

But even with all of her professional and academic achievements, she retains a very special skill from her Peace Corps days: “I can still speak Swahili.”

Micronesia 2015

Bob Hicks ’70

After serving as a school superintendent in Exeter-West Greenwich, South Kingstown and finally on Block Island, Bob Hicks ’70 was thinking about retirement.

“It was 2015, and I was panicking about what I was going to do next,” Hicks said. “Then I saw a story in The New York Times about the Peace Corps.”

Ten days after retiring, he was on a plane to Micronesia as part of the Peace Corps Response program, which sends experienced professionals to short-term, high-impact assignments around the world.

He finished his tour in June 2016 after working on school improvement programs for the Western Pacific nation, which is made of up several islands. One of his first adjustments was to what he called island time.

He recalled a graduation ceremony that was supposed to start at 9 a.m., but a mix-up with his boat transportation put him there about an hour later.

“Still, I was one of the first ones there,” he said. “At 11 a.m., the principal told us a couple of kindergarten children had yet to arrive, and so he was sending someone to get them. ‘It’s their graduation, so we will wait for them.’”

He worked with 60 school principals spread out over a dozen islands to prepare them for their schools’ accreditations. He also helped the Chuuk Department of Education develop improvement teams that would support the schools.

The principals were amazing, Hicks said, now referring to them as his newest best friends. And they were dedicated. When a typhoon approached the area, the governor shut down boat transportation.

“But they came to meet me (by boat) anyway,” Hicks said. “The principals told me, ‘We don’t care who the governor is; he can’t stop our training.’ The vast majority of principals were thrilled to work with us. They are very community focused because the school is the fundamental part of the community.”

The former superintendent had an eye-opening moment when he was showing videos about good American classroom practices.

“Are all American schools segregated?” one principal asked him. “I knew this to be true, but it forced me to confront it. This was an awkward moment.”

While Hicks learned from his trainees and they from him, he also learned how to prepare an entire tuna he bought right off a boat for his meals. On one journey, he saw a flying fish hovering along his boat for about 100 yards. He ate octopus and loved the suction cups.

Hicks also learned that dogs are treated differently in Micronesia, adding that they are never allowed to enter a house.

“When they live out their useful lives, they become dinner. I avoided eating dogs.”

There are also strict mores around interaction between men and women. “If men are seated in a room, women would enter only by crawling or doing a duck walk.”

“Going in the Peace Corps was lifelong goal, but you graduate, get married and get a job,” Hicks said. “My wife, Arlene, said to me, ‘This is your chance. I don’t want you to regret not doing this for the rest of your retirement.’”

“Everything I saw shows that this is the best ambassadorial program we have,” Hicks said. “If you want to promote a positive image of America, there is no better vehicle.”

Guatemala 1965

Paul Farragut ’63

Paul Farragut ’63, who, after completing his undergraduate work, went on to earn two master’s degrees from URI—one in resource economics and one in community planning—never joined the Peace Corps. But the support that Farragut and his fellow graduate students gave the program led to a congratulatory letter from the Peace Corps’ first director, Sargent Shriver.

Now a resident of Ellicott City, Md., Farragut said, “The 60s were an era when public service was viewed positively based on President Kennedy’s famous quote, ‘Ask not what your country can do for you, ask what you can do for your country.’”

That quote inspired the URI Graduate Student Association, including Farragut, to raise $1,000 to build a concrete-block school in Guatemala in partnership with the Peace Corps’ School-to-School program.

In his letter to Farragut dated June 24, 1965, Shriver wrote, “Yours is the first graduate group to undertake a School-to-School project, and I am sure that your public-spiritedness will be an outstanding example to other such groups throughout the United States.

“You are joining with the Peace Corps and an overseas country in a unique partnership. Together you will make it possible for a school to be built in a developing community. Your check will pay for the construction materials, the citizens of the host community will build the school, and the Peace Corps Volunteers will help provide on-the-job-assistance.”

Concluding his letter, Shriver extended his congratulations to the University’s Graduate Student Association.

Farragut also received letters from the school. One was translated by Peace Corps volunteer Lewis Johnson, who played a major role in bringing the school to completion, and it reads, in part: “In the name of the community, we give you our most sincerest appreciation since your contribution has been of vital importance for the realization of the work of the construction of the new school.”

Farragut went on to a 30-year career with the state of Maryland. He ended his working days as executive director of a nonprofit organization in Baltimore.

“We just wanted to help improve their lives,” Farragut said of his Peace Corps fundraising. “The Graduate Student Association was asked and we responded quickly.

We used association dues and we raised some money through socials. One thousand dollars was a lot of money in those days.”

The experience left a lasting impression: “I learned working in public service was a very positive thing to do,” he said. “A career in government can be very satisfying. I always worked with professional people who took pride in what they did.”

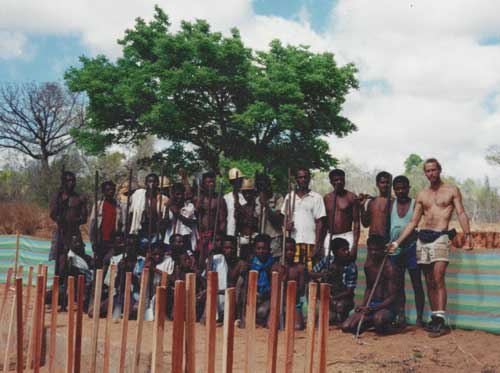

Madagascar 1994

Roland Marquis ’89

“I graduated from the University of Rhode Island in 1989 with a bachelor of science degree in natural resources with a focus on wildlife biology. At that time, wildlife biology was a ‘new’ concept in biological studies. I went right out and started working in various contract positions, involving bird surveys, soil sampling, wetland delineation, and pesticide testing as well as nuisance wildlife control. I also supplemented these jobs with seasonal work as a park ranger.

After nearly seven years, a full-time permanent position was still elusive, so I attempted to find another path. I applied for service in the Peace Corps. With my university degree, work experience and a functional ability to speak French, my application was accepted and I was chosen to be a volunteer in Madagascar.

My start date was August 1994 and Madagascar was very much an unknown country to me. I was assigned to the second group of volunteers in Madagascar and the first environmental forestry program in the country. The needs were great as population was increasing and food production on arable land was reduced, causing the local population to resort to unsustainable slash-and-burn agricultural practices in order to grow foods. This greatly impacted both the forests and wildlife.

I was assigned to a ‘large’ village of 150 people (of the Bara tribe) in the dry deciduous forests in the southwest. My role was to introduce the Peace Corps to rural populations and to assist a local World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) project in the adjacent forest area near my village. We also initiated small assistance projects to help our newfound community.

My work involved the delineation of forest areas for the creation of a national park. The area qualified for national park status based on unique primary forest structure, bird life, lemurs, and the fossa (cat-like carnivorous mammal) that lived there. The forest was under pressure from migrants from the south who used it as grazing land for goats. This was very damaging to the balanced forest structure.

I also worked on erosion berms upslope from the canal that fed the rice fields, helping contain the annual floods and associated siltation.

I am very proud of my service and my time in the developing world. I encounter returned Peace Corps volunteers in almost every segment of the population and the camaraderie is unmatched. I have traveled extensively and have instilled this love in my children. If Peace Corps is still active when I retire, I would consider going somewhere—anywhere. Connecting with others, wherever they may be, is truly a rewarding experience.”

Cameroon 2017

Frances Vazquez ’17

Maybe all the evidence you need to determine if Frances Vazquez will be able to thrive in the Peace Corps is her travel history. As a freshman, she accompanied a professor to Guatemala to assist in a water study centered around easy-to-use clay water filters for developing communities. She studied in Costa Rica during spring 2016 and went to Ghana for a J-term course. Oh, and last year, the Providence resident and Puerto Rico native traveled to Europe with her mother.

She will take her newly earned bachelor’s degree (May 2017) in environmental science and management, her three years of work helping faculty, staff and students at the University’s technology help desk, and all of that travel experience to Cameroon, where she will volunteer for the Peace Corps. She left right after commencement for three months of training before heading to the African nation.

“Even as a student at Classical High School, I thought differently than my friends,” Vazquez said. “They would be buying new clothes and shoes, but that never satisfied my soul,” said the former high school athlete who was required to go straight home after practices or games. I played sports and studied.”

As a Talent Development student at URI, her world expanded when she took an international politics class. An engineering major for two years, she switched to environmental science and learned from professors involved in environmental research and outreach projects around the world.

After her study-abroad semester in Costa Rica, she began thinking about entering the Peace Corps.

“My mother wanted me to go graduate school, but I thought, ‘Now is the perfect time to enter the Peace Corps. I have no bills and no commitments.”

She learned of her acceptance to the Peace Corps while working at the help desk. “I got an email, and I just started shouting.”

Vazquez isn’t sure about her career path after the Peace Corps, but she loves international development and education. “I love science and I have been an artist my whole life, so I would like to incorporate art in science teaching,” Vazquez said. “I could use drawing and other visual aids to illustrate complex concepts.”

But that’s getting ahead of things. As she was closing up the help desk one evening, she looked around at the empty, quiet space in the basement of the Carothers Library and Learning Commons and began tearing up.

“This (URI) is my home,” she said. “I have been here five years, and I have so many great relationships, so many great friends. I really grew up here.”

Guyana 1964

Joseph Johnson III ’65

“What do I do now?” Joseph Johnson III ’65 asked himself in the fall semester of 1964. “I had been in school since 1949.

“Vietnam was on my mind, and the military was not a great option,” so the physical education major checked out the Peace Corps. “I met with Peace Corps recruiters right after Thanksgiving in 1964 and was accepted for a tour in Guyana, which had just become an independent country.”

He thought he would be teaching physical education to schoolchildren, but that didn’t work out. “But that was OK, because the Peace Corps teaches you to adapt and how to respond to different experiences. I taught reading, writing and mathematics to fourth graders,” said Johnson, who also became a construction worker during his service.

“The school in one of the little villages was made of bamboo and thatch, and during the rainy season, school could not be held,” Johnson said. So with lumber and cement supplied by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), Johnson, his fellow volunteers, and the villagers built a weather-proof structure.

“We were supposed to get a technical advisor, but one never came, so we took the boards, made forms and used them to make a concrete block structure,” he said. “So, I taught in the early part of the day, and then would go to work at 2 p.m. to help build the school. In two months, we finished a pretty good structure that had a strong roof and solid walls. That felt really good because we could hold school in the rainy season.”

But that wasn’t it for Johnson. When volunteers didn’t show up to help boys at a detention school and orphanage, he taught physical education there and developed some organized recreation. “I introduced volleyball with just a string for the net and a soccer ball,” Johnson said. “I brought some structure to it, kind of like an intramural set up. We also played an abbreviated form of cricket.”

He called his service an enormous challenge, especially because there was no electricity, no clean running water, and no immediate source of food. “Sometimes, I didn’t get to bathe for three months, but guess what, I am still here,” Johnson said.

He said there was a mental challenge, too, which was “how to introduce change without being the know-it-all, ugly American. Volunteers are faced with how much of the local culture does one want to embrace while trying to be true to one’s own value system. Learning how to bend is critical.”

He stayed in touch with his fellow volunteers and earned a Peace Corps scholarship to attend Springfield College for his master’s degree. He taught grade-school children for a short period, but then earned another master’s degree in special education. That led him to spend most of his career as a special educator in the Norwood, Mass. school district.

He said the Peace Corps inspired him in many ways and the experience has stayed with him over the decades. “I so firmly believe that the globe is small enough that we are all truly neighbors,” said the 70-year-old retired teacher. “It’s incumbent that we get our neighbors—that we appreciate them and understand them.”

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus