Ambassadors of Global Health

Out of Africa

When Michaela Maynard ’07 was in fourth grade she wanted to become a pediatric oncologist.

When Michaela Maynard ’07 was in fourth grade she wanted to become a pediatric oncologist.

Although her focus has altered, she still wants to be a physician. A class in emerging infectious diseases and trips to Honduras made her aware of the inequality of health care and inspired her to work in the world’s most impoverished countries.

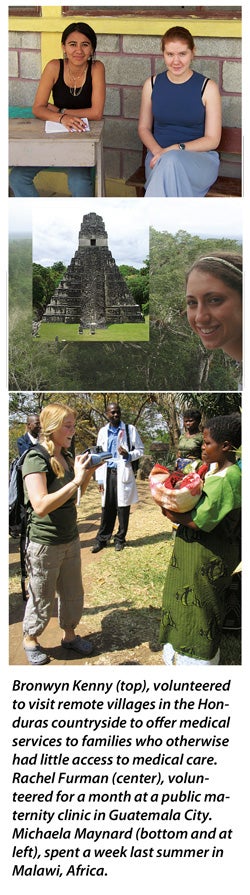

After graduating with a degree in Spanish and completing all of her pre-med courses, she spent a week last summer in Malawi, Africa. The trip, the top prize in an essay contest about health and the dignity of women sponsored by the United Nations Population Fund, confirmed her commitment.

Maynard visited a medical clinic, hospitals, and orphanages and learned about the fund’s work.

“I felt really helpless seeing rows of pregnant women sitting on the floor of a hospital room because there weren’t enough beds,” she says. “I couldn’t help but picture the high-tech neonatal intensive care unit at Women & Infants Hospital in Providence with incubators, closets full of vital medications, and plenty of room for all the mothers and babies.

“At the same time, I felt confident that these women were getting the best treatment available in Malawi and that their doctors, nurses, and midwifes were working tirelessly to ensure every woman’s health and dignity. I just wish that they could have more—more space, more money, more doctors, more access, and most importantly, more lives saved.

“Now that I’m home, all I can think about is how and when I’m going to return to Africa. In the meantime, I’ll work on ways to support the Malawians while I’m enrolled in George Washington University’s two-year master of public health program.”

Maynard expects to enter medical school by 2009.

—By Jan Wenzel ’87

A Change of Course

Sometime during her sophomore year, Bronwyn Kenny ’05 decided she wanted to become a doctor.

“Academically, my strong points were writing and humanities, but I had become more interested in the sciences,” she said.

Kenny spent the next three years studying biology and working for the URI Emergency Medical Services, where she earned her EMT certification and found she had a knack for patient care and teamwork. She became interested in infectious diseases through an honors course and a summer Lyme disease project, which convinced her to put off medical school for a year to continue her research.

A winter trip to Honduras last year reinforced her desire to become a doctor. Kenny joined a group of Rhode Islanders who volunteered to visit remote villages in the Honduras countryside to offer medical services to families who otherwise had little access to medical care.

“We had 50 people in our brigade, and every day we would hike to outlying villages and set up a clinic in a schoolroom,” Kenny explained. “People would bring in their families for physicals and medications. It was an eye-opening experience.”

Kenny found people in Santa Lucia (the nearest village) flourishing, but just a two-hour drive away she found poverty —little electricity, little access to clean water, and failing crops. There were very few intact families because the men were elsewhere picking bananas or coffee.

Kenny served as a pharmacy technician and, by the end of the project, had learned how to explain the directions for taking various medications in Spanish.

Motivated by her Honduras experience and her newfound confidence speaking Spanish, Kenny entered the St. Louis University Medical School this fall.

—By Todd McLeish

Good Health in Any Language

Rachel Furman ’07 always enjoyed learning languages. She learned Hebrew at home, took courses in Portuguese and French in high school, and fell in love with Spanish, which became her academic major at URI.

A growing interest in women’s health issues that she developed on a trip to Guatemala last January, coupled with an infectious disease honors course, convinced Furman to merge her passions and pursue a career in public health in Latin America.

“What was unsettling to me in Guatemala was the unequal distribution of health care,” explained Furman. “Those living in or near the capital could access health clinics, but those living in remote rural areas are likely to deliver their children without proper medical care.”

She volunteered for a month at a public maternity clinic in Guatemala City, taking vital signs, helping with prenatal exams, coaching women in labor, and offering them comfort during delivery.

“I didn’t have a medical background, but I am a quick learner,“ Furman said. “The clinic lacked a lot of resources—the beds were iron cots with few pillows —yet the doctors did a wonderful job.”

Guatemala wasn’t Furman’s first visit to Latin America. As a sophomore, she planned her own study abroad itinerary, beginning with an intensive language training experience in Buenos Aires, Argentina, followed by six weeks of classes in Valparaiso, Chile, at the Universidad la Catolica, and concluding with three weeks of backpacking around Peru.

Furman is taking a year out of school to find a job in public health before enrolling in medical school.

—By Todd McLeish

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus