Hot Food and Comfort at Ground Zero

From the QuadAngles Archives

Those We Lost: A tribute to the five URI alumni who lost their lives on September 11, 2001

Witnesses to History: Ten alumni who witnessed the events of September 11 share their stories

Taking care of 9/11’s first responders

When Brian Bresnahan graduated from URI in 1982 with a degree in political science and communications, he envisioned a life in politics. His uncle John had served in the Massachusetts state legislature for 25 years; another uncle, Joe, for 14. “I came from a political family,” he explains. So it was no surprise that, degrees in hand, Brian moved home and launched a campaign for a seat as a state representative: “Eleven candidates were vying for the retiring incumbent’s seat; I came up second. Sue Tucker, the winner, was certainly more qualified.”

With campaign bills to pay, a job with Airborne Freight in Boston came at the perfect time. It wasn’t long before a competitor noticed him; 14 months later, FedEx offered him a position. “There was a three month break between jobs, so I went to Europe to backpack.” He visited eight countries, often meeting up with family and friends along the way.

With campaign bills to pay, a job with Airborne Freight in Boston came at the perfect time. It wasn’t long before a competitor noticed him; 14 months later, FedEx offered him a position. “There was a three month break between jobs, so I went to Europe to backpack.” He visited eight countries, often meeting up with family and friends along the way.

Brian’s eight-year career with FedEx was a good one. He was eventually promoted to national accounts executive, a role that gave him the opportunity to take two top accounts, L.L. Bean and Digital, to the 1988 winter Olympics. It was a life-changing experience. “Taking those clients to the Olympic games and being at an international event watching U.S. athletes compete really solidified our business relationship. When my friend Dave picked me up at the airport, I told him I’d discovered what I want to do—start a company that creates events and experiences for corporations.

What he did first, though, was stay with FedEx, expanding its marketing programs with the Olympics, PGA, and other international sponsorships. By 1998, he was ready to go out on his own. He founded Intrepid Creative Events, a marketing and advertising agency in Atlanta that “specializes in creating blockbuster, proprietary, and original sales, marketing, and opportunities for brands, corporations, and individuals.” His first client: Coca-Cola. Today, the list includes a slew of equally familiar names: Smuckers, GTE, Uncle Ben’s, Johnson & Johnson, Lego, and U.S. Armed Forces Sports to name a handful.

By all accounts, Bresnahan excels at what he does, especially at experiential marketing. He explains experiential marketing as “creating a buzz, a marketing mix, a thunderstorm of activity around a brand to promote a company’s objectives and cause.”

For example, he orchestrated a partnership between Maxwell House® and Habitat for Humanity to “build 100 houses across the country in 100 weeks.” Maxwell House donated $2 million and supplied volunteers, bonding with Habitat staff and home-owners. “When clients moved into their new home, Maxwell House coffee was in the kitchen cupboard.”

Bresnahan recognizes the power of adding a philanthropic element to the mix, but he’s quick to add that it isn’t just about good marketing, “it’s about wanting to do the right thing for the right reason.”

And so, on September 8, 2001, Brian was in Boston, sponsoring a Susan G. Komen Race for the Cure fundraiser for a client, Uncle Ben’s®. The venue was part of a national mobile sampling tour to introduce the company’s new rice and noodle bowls with sales benefiting the Komen Foundation, a leader in breast cancer research.

Bresnahan had flown from Atlanta that morning to join his four-person team at the event: “It was a crystal clear day. I remember the Delta pilot coming on the speaker and saying, ‘Off to the left, ladies and gentlemen, is a beautiful view of Manhattan.’ I was sitting in the middle of a row, buckled in. I thought, ‘I‘m not getting up to look; I see this six times a year.‘”

From the Komen event, Bresnahan drove to Andover, Mass., to stay with his parents for the weekend. He had a business meeting scheduled for Monday, September 10, at Foxwoods negotiating an event for ice skater Brian Boitano with tickets to fly home the following day. “My Foxwoods contact had a personal emergency, so we rescheduled the meeting to Tuesday, the 11th. It gave me an extra day with my parents.”

He was in transit, listening to the radio, when an emergency announcement came on—something about a plane flying into the World Trade Center.

Auspicious Timing

Bresnahan’s one-hour meeting was condensed into five minutes. He got on the phone with his employees in Boston, “stay put.” Then, he called his client: “We’re four hours from New York City in a 42-foot mobile kitchen. We have 12 industrial microwave ovens, water, a generator, and a freezer trailer. We could help.” On the morning of September 12, Brian was given authorization with two conditions: “Make certain none of your employees gets hurt; two, this is not to be a marketing event for our company; this is only about helping.”

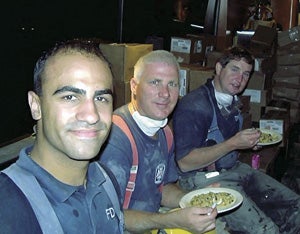

The next hurdle was getting permission to take the mobile kitchen to the first responders: “We were all on our phones—to Mayor Giuliani’s office, to FEMA headquarters—but we weren’t able to get through. So we drove to Shea Stadium.” Eventually, Bresnahan was able to convince a couple of cops to intervene: “We were escorted to 100 yards from where the Towers once stood. They were still smoldering. Within 20 minutes we had the generator powered up, the microwaves humming, and were handing out meals. There was a line 100-men deep waiting to get hot chicken and rice and beef and noodles.

“The scene outside was horrific. Buildings were burning, debris was falling, a thick layer of white ash covered everything, like a nuclear winter. Every time a siren went off [warning of possible building collapse], my staff would have to run toward the Hudson River, 100 yards away.”

Over the next 40 days, the kitchen-on-wheels would serve 60,000 free meals. Bresnahan’s admiration for his team is boundless: “We worked 18 to 20 hours a day, dashing back to the hotel to sleep for a few hours, timing it so we’d be working whenever the responders were on break.”

After nine days, Bresnahan flew home: “I had two young kids in Atlanta, my one-year-old son, Ben, and my six-year-old daughter, Meredith.” Two days later, he was back in New York. “I found myself going back and forth over the course of the 40 days my crew was there. One night I was giving a new relief person a little tour around the financial district. We walked by O’Hara’s Bar, off Liberty Street, and were greeted at the door by a steel worker with a menu in his hand, ‘table for two?‘ he asked. The place had been turned into a self-serve bar for steelworkers on break. We just stuck our heads in, but I took the menu. It’s one of the few artifacts I have. It’s a lunch menu dated September 10; they hadn’t had a chance to put out the September 11 menus.”

While Bresnahan and his team were hunkered down keeping the hot food coming, they had some surprise visitors: “Everybody was coming by the bus to lift people’s spirits: President Bush, Mayor Giuliani, Robert DeNiro. To be in the middle of the national movement to help those first responders was amazing.”

Fast forward to the one-year anniversary: “I was invited by some of the FDNY and NYPD to attend the memorial service. After a somber day of hearing the tributes to the deceased, I went back to O’Hara’s Bar with the police officers and firemen. They had this impromptu ceremony and started nailing their badges to the mahogany bar. A big burly fireman from Oklahoma came up to me and said ‘weren‘t you with us, feeding us out of that big orange bus?’ He pulled out a huge Bowie knife, cut my tie off my neck, and nailed it over the bar.

“On the way to my car, I passed Cokie Roberts of NPR interviewing people on the street, asking where they had been a year earlier. She turned to me, but I was not able to speak. We just felt so fortunate that we were in the right place at the right time with the right equipment to help.”

A Changed Perspective

Although Bresnahan rarely talks about it, those days in New York City changed him. “With an event like 9/11, your perspective changes. You start thinking about family, and leaving a legacy.”

A devoted dad who is active in his kids’ school life and sports activities (his daughter recently teased that he was “the only dad with a white board at home, like the teachers!”), it was a natural for Bresnahan to launch the Healthy Kids Across America Foundation last year. Dedicated to improving children’s nutrition, physical activity, and self-esteem, he has reached out to local and national figures (Michelle Obama is one) and has received enthusiastic support. For more information, go to healthykidsacrossamerica.org.

Bresnahan notes, “I’ve never been a small thinker. If you swing for singles, you get singles; if you swing for a home run you may get one—or at least a double.”

Martha Murphy ’80

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus