Woolly Tale

A pioneering student recalls a work-study job like no other: Getting a live ram game-day ready.

By Nicole Maranhas

Margaret (Hogan) Burns ’64, M.S. ’66, doesn’t remember exactly when late Professor Bancroft Henderson enlisted her for the job of grooming the ram mascot before University football games—if it was her senior year as an undergraduate or during her two years as a research assistant—but she still remembers her duties well. Burns has been caring for sheep since the age of 10, when her parents bought her a pet lamb before the family moved from Fall River, Mass., to a dairy farm in Tiverton, R.I. She instantly took to farm life, enrolling at URI as an animal science major in what was then the College of Agriculture. “I was the only girl in all my classes,” recalls Burns, whose years of experience preparing sheep for 4-H Club shows made her an ideal candidate for ensuring the beloved mascot—an actual sheep in those days—was game-day ready.

Margaret (Hogan) Burns ’64, M.S. ’66, doesn’t remember exactly when late Professor Bancroft Henderson enlisted her for the job of grooming the ram mascot before University football games—if it was her senior year as an undergraduate or during her two years as a research assistant—but she still remembers her duties well. Burns has been caring for sheep since the age of 10, when her parents bought her a pet lamb before the family moved from Fall River, Mass., to a dairy farm in Tiverton, R.I. She instantly took to farm life, enrolling at URI as an animal science major in what was then the College of Agriculture. “I was the only girl in all my classes,” recalls Burns, whose years of experience preparing sheep for 4-H Club shows made her an ideal candidate for ensuring the beloved mascot—an actual sheep in those days—was game-day ready.

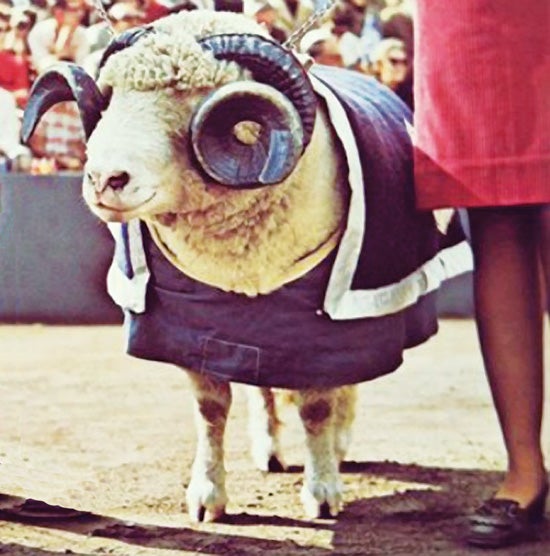

As with the athletes, preparation for the mascot began in the preseason. The first order of business was choosing the perfect ram from the University’s flock of horned Dorset sheep. “He needed to look exactly like the campus statue, big and blocky with curls to his horns,” says Burns.

Next, the mascot had to be trained. “Rams, compared to ewes, can be very dangerous. It was important to halter-train the ram so he could be taken to the football games.” (A new ram was trained every two or three years, says Burns; after a few years, the trained ram could start to become surly or difficult to handle.) Shearing was also key: “You had to make sure you sheared the ram at the right time so that it would grow back an inch of wool before the season,” says Burns.

When football season was underway, each grooming session typically took about a day. “Before a game, I would wash and trim him, then card him up [a process similar to combing] until his fibers became smooth,” she says. Once Rhody was picture-perfect, Burns would cover him with a blanket to keep him clean until game time.

URI discontinued the tradition of having a live ram at football games in 1974, not too long after Burns earned her master’s in biochemistry and statistics, writing her animal nutrition thesis on digestion trials done with the URI sheep flock. “I had wanted to become a veterinarian,” she says, “but very few females were accepted into vet school back then.” She instead spent much of her career as a research scientist at the University of Connecticut, where her work included researching snake venoms at the College of Pharmacy. (With a laugh, she recalls the “ramnapping” rivalry that waged between URI and UConn for years.) Still, she never lost her affinity for sheep; she was a 4-H Club leader for more than 30 years and currently keeps a flock of about 80 at her home in North Carolina. “Sheep aren’t dumb like people always think,” she says. “They’re very smart, and they have a super memory.” •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus