A Vaccine for Nicotine

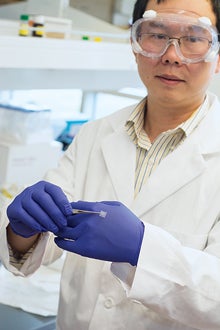

URI pharmacy researcher Xinyuan “Shawn” Chen is working on a vaccine that would inoculate people against nicotine’s addictive properties, coupled with a novel skin delivery system that could revolutionize the way all vaccines are delivered.

Right now, there are nicotine patches aimed at people trying to give up smoking, but they simply deliver a low dose of the potent drug to ease cravings. Chen is working on something very different: a vaccine that would trigger a user’s own immune system to block nicotine’s entry into the brain.

There are no approved nicotine vaccines on the market at present, partly because to be effective, the vaccine requires powerful adjuvants, substances that would be toxic if injected. That’s where the patch comes in. In a painless process, skin is pierced by a laser to form an array of micro-channels, then a small square of contact lens material filled with tiny dots of powder is placed on top. The clear patch, which is about the size of a thumbnail, can deliver 810 micrograms of medicine—as opposed to the 45 micrograms contained in a typical flu shot—and do it without triggering a painful reaction.

The patches would also travel and store well.

“Generally, vaccines are liquid, but powdered vaccines are more convenient and they have a longer shelf life,” Chen says.

The assistant professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences has a lab in URI’s three-year-old, $75-million College of Pharmacy building. He came here last year from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, bringing with him a $1.08-million career development grant from the National Institute of Drug Abuse and a $432,000 grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The technology will need several years before it’s ready for clinical tests and FDA approval, but Chen is already imagining a different world, with fewer smokers, and one with children who don’t fear the doctor’s office because the 30 or 40 vaccine injections the typical baby receives will be a thing of the past.

“We want to help those who are already addicted to nicotine, to help them quit smoking,” he says. “We also believe for other vaccines, that we could put multiple vaccines in one patch, thereby eliminating the need for multiple injections.”

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus