Renowned Paleontologist Leaves URI after Storied Career

written by Chris Barrett ’08

In 1991, David Fastovsky redrew our understanding of the dinosaur extinction.

David Fastovsky accepted the first professional job anyone ever offered to him while he was still writing his Ph.D. thesis in graduate school. Thirty-six years later, he’ll retire from the University of Rhode Island (URI) after a distinguished career that brought him international acclaim in paleontology.

“I wanted to be a paleontologist when I grew up, and URI let me be a paleontologist,” says Fastovsky, a geosciences professor.

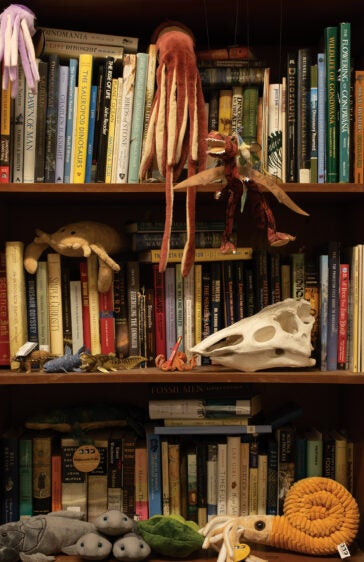

During his time at URI, Fastovsky discovered first-of-their time fossils, published the best-selling undergraduate dinosaur textbook, and edited scientific publications, among many other things – all while teaching tremendously popular courses.

Fastovsky combined his sedimentology expertise and love of dinosaurs to study the geology around fossils. That let him paint a picture of the Earth’s environments hundreds of millions of years ago. And in 1991, he redrew our understanding of the dinosaur extinction.

“We climbed volcanoes at night, visited the Komodo dragons, and crossed the Wallace Line several times.”

–Thomas Boving

At the time, conventional wisdom held that the non-avian dinosaurs that went extinct 66 million years ago experienced a gradual decline. Fastovsky and colleagues showed evidence that pointed to a more sudden death, startling even him. But he found support at URI, especially at the Graduate School of Oceanography.

“I really felt like I was comfortable; I had people to talk to about the work I was doing,” Fastovsky says of URI.

Most paleontologists eventually embraced Fastovsky’s findings. The Milwaukee Public Museum even created a diorama that features a wax likeness of him.

Fastovsky’s research didn’t stop. A 2004 Fulbright Scholarship sent him to Mexico, and he now conducts annual fieldwork there. One memorable Mexico trip brought him to Huizachal Canyon where 189-million-year-old volcanic ash deposits contain fossils.

On the other side of the world in Mongolia in 2011, he described a 70-million-year-old nest containing the fossilized remains of 15 baby Protoceratops andrewsi dinosaurs in a first-of-its-kind discovery.

Then in 2015, Fastovsky traveled to Europe on his second Fulbright Scholarship. He taught about mass extinctions at the University of Vienna and sifted through French deposits to look for clues to the dinosaur extinction.

“URI has been, in my experience, a really humane institution, the playing field has always been level and people try to do the right thing.”

–David Fastovsky

In between field work, Fastovsky wrote a book about, not surprisingly, dinosaurs. Turned into a textbook, it’s now in its fourth edition with talk of a fifth. He’s also served as science editor for three geosciences academic journals.

He also teaches. His first URI dinosaur course fit in a regular classroom. By his sixth year, administrators assigned him to Edwards Auditorium to accommodate 540 students. Fastovsky notes that he taught without teaching assistants and even once contended with a horse ridden into the building. The rider sought a woman whom he suspected was in the class, but eventually took his exit when no one rose to his calls. That specific young woman later told Fastovsky that she was indeed in the auditorium at the time, but she had no romantic interest in the rider.

Students also tell the professor the stereotypes that pop culture perpetuates about paleontologists and Fastovsky rectifies them. Unlike paleontologists in the movies, Fastovsky wears his shirt in the field – the sun is real danger – he does not carry a knife, he never battled a chamber of snakes, and he does not “dig” for fossils, but searches along the surface for exposed objects.

Fastovsky knows a thing or two about the sands that cloak fossils. URI geosciences Professor Thomas Boving recalls a trip to Indonesia with Fastovsky and his students.

“We climbed volcanoes at night, visited the Komodo dragons, and crossed the Wallace Line several times,” Boving says. “David not only impressed me and our students by his immense knowledge about all kinds of things geological and non-geological, but he also turned out to be a healer and shaman. If it weren’t for him, we would have lost several of our students to various illnesses–real or imagined–including occasional emotional breakdowns.”

Most recently, Fastovsky and his students faced the COVID-19 pandemic. When administrators called back his annual spring sedimentology class field trip to Arizona and Utah, he pivoted to online teaching. The professor is quick to say that URI is a compassionate university that created a safe environment during the pandemic.

“URI has been, in my experience, a really humane institution,” he says. “The playing field has always been level and people try to do the right thing.”

When he walks out the door of Woodward Hall in December, Fastovsky will not leave the institution entirely. He lives nearby–he bikes to work year-round–and plans to continue to partner with one of his students to publish a book about social justice as part of evolutionary biology, as well as work on that fifth edition of his textbook. Plus, there’s the occasional coffee breaks with his dear colleague, Professor Boving, and also responding to dinosaur listservs where some theories call for the patient, educated response of a professor.

But Fastovsky won’t just be thinking about dinosaurs. A local bicycle shop extended a part-time job offer, so Fastovsky did what he did last time someone offered him a job. He accepted.