I am writing this article while having the absolute pleasure of co-teaching one of the University of Rhode Island’s (URI) January-Term (J-Term) field schools along with two of our most talented educators, Professor Rod Mather, marine historical archaeologist, College of Arts & Sciences, and Diving Safety Officer Anya Hanson, director of URI’s diving research and safety program.

We have eight terrific students with us who are all acquiring proficiencies as certified research divers and exploring sunken wrecks and anchors dating back to the battles between the English and Spanish for control of British Honduras (now, Belize) in the 18th and 19th centuries. My role has been to focus attention on how humans alter and pollute this precious marine environment, particularly highlighting the impact of plastics pollution (as well as URI’s focused efforts to address this massive issue through our Plastics: Land to Sea Initiative).

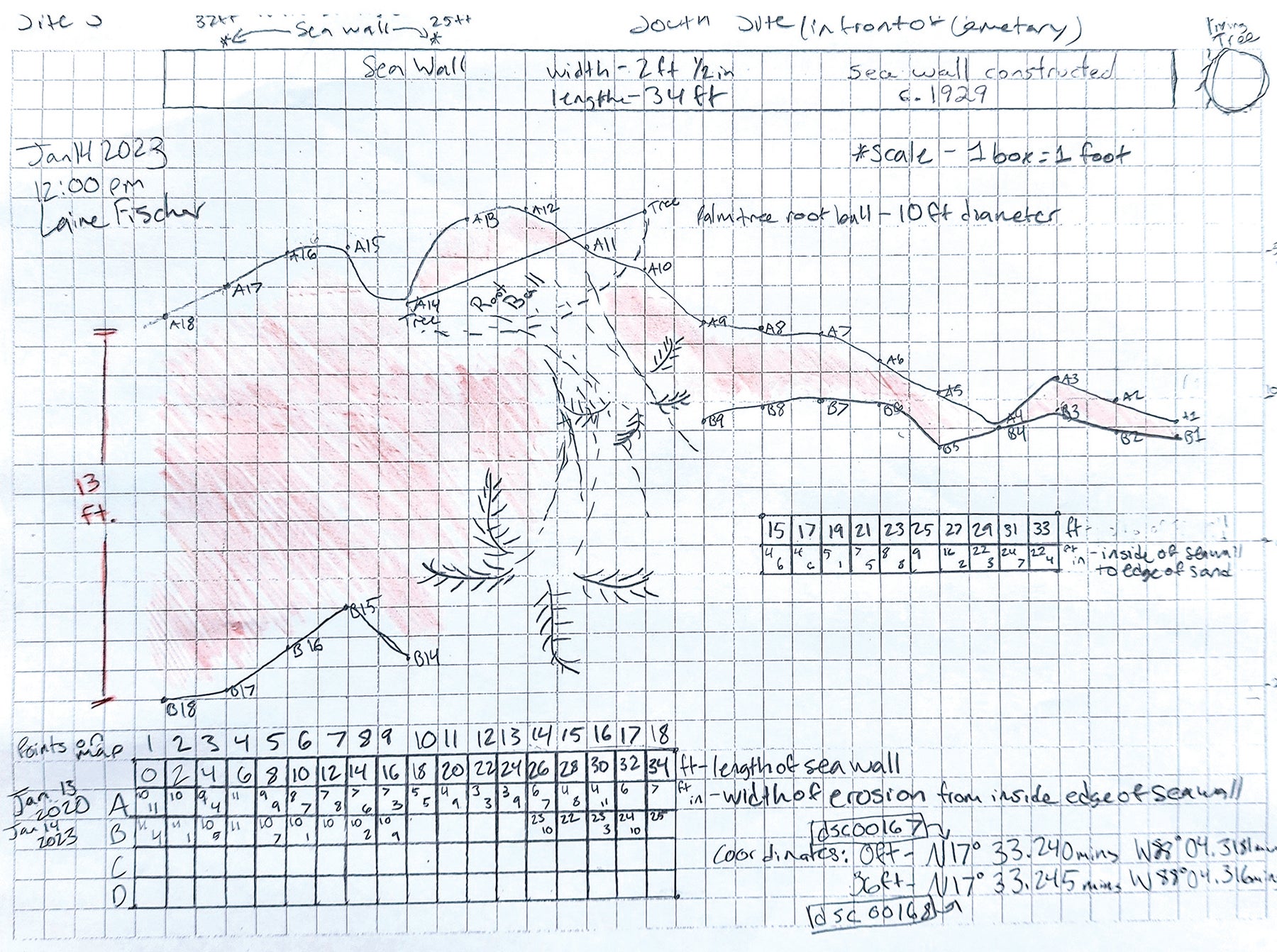

As part of this educational module within the course, we have led the students in mapping the extent of coastal erosion around the island (compared to our prior survey of the same locations three years ago with another J-Term class) in picking up nearly 200 pounds of plastic litter from the beaches of St. George’s Caye and searching for and counting manmade refuse on our many dives. We have read relevant articles together and have engaged in nightly discussions on the fate and transport of plastics, on their impacts on both marine fauna, the food web, and potentially human health.

Our conversations also incorporate the socio-economic drivers of plastics pollution that are more visibly obvious in countries like Belize. We focused on the hard work of educating communities and encouraging cultural change, and on the varied multi-disciplinary research and important projects that URI scientists are leading in response to this global crisis. One afternoon, three of our students led me down a pathway to show me a discovery — a massive garbage dump hidden in the coconut trees and mangroves alongside the water’s edge in the bay. This poorly hidden site was being actively used by the only vacation resort on the island. Hidden from the sight of their well-heeled resort guests, the staff throw refuse there every day.

“Our students learned how to SCUBA dive on sensitive archaeological sites and within fragile ecological areas, and the basics of professional work as research divers.”Peter J. Snyder

There were large and well-used burn pits right on the beach within the intertidal zone. The plant life around the dump looked sick or dying, and there were none of the juvenile fish that we would expect to see swimming under the protective root systems of the mangrove trees. The discovery lead to a long conversation about why government regulations are difficult to enforce on this remote island, the costs and logistics of proper trash disposal, and the more pressing concerns for local inhabitants. This was an eye opener for all of us, and for me it highlighted why URI’s field schools – and the chance for students to engage in foreign travel and experiential learning – are so singularly important to our mission as a research university.

The sea wall, constructed in 1931, was high enough to protect the soil from erosion. At this time the wall is largely underwater most of the day.

Throughout this trip, buzzing in the back of my mind had been a television show that I watched on our flight to Belize, namely, an episode of the television series “Anthony Bourdain: No Reservations.” Bourdain was an acclaimed chef, a keen observer of the human condition, and a natural educator. The episode that I watched on our flight here delved into the history, cuisine, and culture of Nicaragua (Season 7, Episode 3, March, 2011) and provided a glimpse into his deep anguish about how humans can treat both each other and our environment. He documented the lives of the poorest members of Nicaraguan society, “los churecos” (meaning, people of the garbage dump, in the capital city of Managua).

While filming the roughly 300 families who live in the dump and eek out the most meager of livings searching the ever-growing mountains of waste for items to both and to eat, he observed a young girl who was roughly the same age of his own daughter. There, on camera, Bourdain nearly lost his composure and openly mourned this human tragedy. He revealed his deep compassion, anger, and personal regret at living a life that is separate and removed from such inequity (Anthony Bourdain Nicaragua Clip – YouTube).

Two days after watching this in-flight program, I sat on a beach close to where we were lodged on this island and I privately cried when my first new measurements of our coastal erosion mapping showed a loss of nearly four feet of land in just three years, as well as dramatically more plastic waste on these same beaches (much of it washed ashore from Belize City and from many other places throughout the Caribbean and Central America) compared to our observations just a few years ago.

To quote Anthony Bourdain: “Travel isn’t always pretty. It isn’t always comfortable. Sometimes it hurts, it even breaks your heart. But that’s okay. The journey changes you; it should change you. It leaves marks on your memory, on your consciousness, on your heart and on your body. You take something with you. Hopefully, you leave something good behind.”

Our students learned how to SCUBA dive on sensitive archaeological sites and within fragile ecological areas, and the basics of professional work as research divers. They learned much about the local history and marine environment of this country, and became fast friends with each other and the wonderful local staff of the Ecomar biological station on this island. They were also passionately engaged in balancing the natural beauty around us with their increasing awareness of the very real and present threats to the long-term health of this special place because of global warming, coastal erosion, and human contamination.

Our students learned how to SCUBA dive on sensitive archaeological sites and within fragile ecological areas, and the basics of professional work as research divers. They learned much about the local history and marine environment of this country, and became fast friends with each other and the wonderful local staff of the Ecomar biological station on this island. They were also passionately engaged in balancing the natural beauty around us with their increasing awareness of the very real and present threats to the long-term health of this special place because of global warming, coastal erosion, and human contamination.

They discussed the history and marketing of plastics, the roles of international treaties and current U.N. negotiations on plastic waste, needed improvements in maritime laws, and the role of economics and education on moderating these destructive forces. I overheard several of our students talking together about how they can take steps at home to reduce their use of plastic products, how washing and drying synthetic clothing releases many hundreds of millions of nanoplastics (per household) into our wastewater each year, and how they and their friends should resist the fast-fashion marketing that is directed squarely at their age group.

As Anthony Bourdain noted for himself, those 10 days of travel changed our students. This experience will indeed leave marks on their consciousness and on their hearts. And, they left something good behind — slightly cleaner beaches.

– Written by Peter J. Snyder, Ph.D. Former Vice President for Research and Economic Development, Professor of Biomedical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Professor of Art and Art History, University of Rhode Island