The NSF Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF) provides students a stipend and wide latitude to undertake an independent research project. This is essential to their training for becoming independent innovators.

Dean of URI’s College of Arts and Sciences Brenton DeBoef calls the GRF a “golden ticket” reserved for America’s top students. Each year, a few fellows select URI. They receive tuition and a stipend for five years with three years paid by NSF and two paid by the institution.

Professor, Chemistry

“It’s a game changer for the research group they join because they’re funded on their own and it gives them independence, and it unlocks the ability for future awards,” DeBoef says.

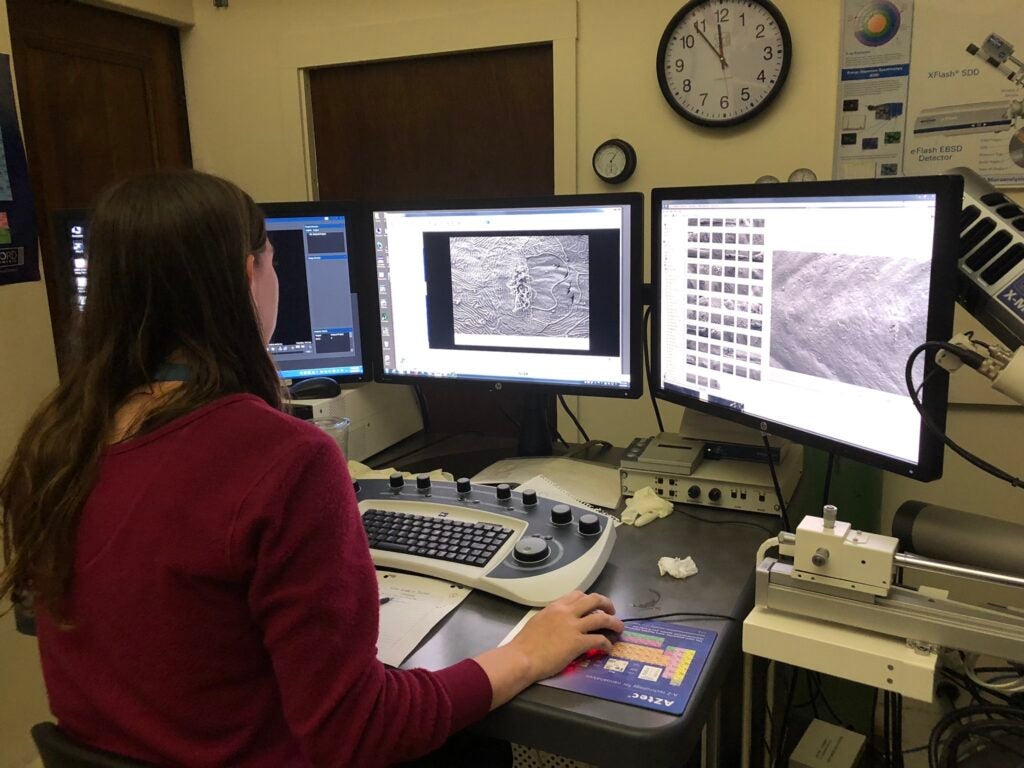

Aubree Jones ’23, a biological and environmental sciences doctoral student, applied for the fellowship as a URI master’s student. Awarded a GRF in 2018, she started research on a fish sensory system called the lateral line, which detects nearby water flows and vibrations.

One connection led to another, and NSF awarded her more money under the Non-Academic Research Internships for Graduate Students (INTERN) program to work with the Geological Survey Eastern Ecological Science Center. The funding supported Jones’ collaborators to rear brook trout at different temperatures at the Silvio O. Conte Anadromous Fish Laboratory for her dissertation research.

Working with researchers at the Massachusetts lab, Jones found that warmer water temperatures sped up the development of the lateral lines. With water temperatures rising due to climate change, the finding indicates that the trout might grow out of sync with the surrounding environment and mature faster than food becomes available. That could mean disaster for everyone from recreational anglers to commercial fishermen, to say nothing of the larger environmental impact.

Then there’s the tiny lateral line receptors in the fish – remarkably like those in a human ear but they can regenerate, whereas human receptors cannot. Jones studied how these receptors develop and regenerate under different conditions, which provides the framework for other researchers to leverage and treat human hearing loss.

The scientific community would define much of her work as “basic” research, rather than “applied” but Jones says her research is critically important.

“Basic research represents building blocks,” she explains. “Underneath each of those studies that get sufficient accolades there’s hundreds, if not higher orders of magnitude more, of basic research that needed to be done.”

Today, Jones teaches biological sciences at Wellesley College, where she mentors students and encourages them to apply for research funding just like she did. And, who knows, some might even apply to URI.