Neurodegenerative diseases—which include Alzheimer’s disease, ALS (amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), Parkinson’s disease, and age-related dementia—have a devastating impact on the lives of millions and are some of the most complex and challenging conditions to understand and treat. The University of Rhode Island (URI) aims to tackle this crisis. By growing a strong biomedical sciences ecosystem, URI enhances our state’s attractiveness to biotechnology companies and startups, spurring job creation and economic development.

The George & Anne Ryan Institute for Neuroscience, established in 2013 by Tom Ryan ’75 Hon ’99 and his wife, Cathy, is home to an interdisciplinary group of nine core faculty, as well as a network of affiliated URI faculty, based throughout the Colleges of Pharmacy, Health Sciences, Environmental and Life Sciences, and Engineering. This dedicated team, led by co-executive directors and URI professors John Robinson and William Van Nostrand, investigate how and why neurodegenerative diseases develop and seeks innovative solutions.

(Right) JOHN ROBINSON Co-Executive Director; Thomas M. Ryan Professor of Neuroscience Professor, Psychology and Biomedical/ Pharmaceutical Sciences

Neuroscience is a point of pride for URI with tremendous opportunity for growth. By attracting top scientific talent to the area, training students, and forming collaborative partnerships, URI has very quickly become a dynamic neuroscience and biomedical research community.John Robinson

Robinson has helped advance the understanding of the role of diet, exercise, and cognitive stimulation on the progression of Alzheimer’s disease and other similar conditions.

“We know now that Alzheimer’s disease and other age-related disorders are not determined by a single cause,” he says. “They are most likely diseases with multiple contributors that will require more than one form of treatment, and those will not necessarily be the same for every individual.”

By understanding the pathological mechanisms of these diseases, we can identify biomarkers that could lead to earlier or improved diagnosis, treatment, and ultimately prevention.William Van Nostrand

A biochemist by training, Van Nostrand has focused his research career on the role of blood vessels in Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders. Early in his career he identified an enzyme inhibitor that he found to be the progenitor of amyloid beta, a protein that accumulates abnormally in the brain of those with Alzheimer’s disease. His expertise in cerebral amyloid angiopathy, which causes bleeding in the brain, could be key to understanding related disorders, including hypertension.

Van Nostrand began collaboration with pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly in January 2024 to investigate the bleeding risk associated with newly FDA-approved Alzheimer’s disease treatments. He also collaborated with Alnylam Pharmaceuticals in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on a drug to stop the over-accumulation of amyloid-beta protein that plays a role in Alzheimer’s disease. MindImmune Therapeutics, an independent biotech company based at URI and affiliated with the Ryan Institute, plans to begin clinical testing of an Alzheimer’s antibody drug late next year.

“We see that many diseases that affect the brain blood vessels have certain pathologies in common,” Van Nostrand says. “If we can better understand the molecular mechanisms involved, we may be able to find targets for multiple disorders that lead to dementia.”

But the Ryan Institute’s mission transcends intervention in active disease. Neurodegenerative disease prevention is another of its key aims. For example, Jessica Alber, assistant professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences and Ryan research assistant professor of neuroscience, holds a $10 million grant at Butler Hospital Memory and Aging Program in Providence to study possible screenings for early-stage Alzheimer’s disease in a regular eye exam. This could provide a much-needed way to diagnose and treat the disease before symptoms appear.

Demonstrating the Ryan Institute’s ability for interdisciplinary investigation, Katharina Quinlan, associate professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences and Ryan research associate professor of neuroscience, studies ALS, spinal muscular atrophy (another degenerative condition that affects one’s ability to move) and the impacts of injury to the nervous system in conditions like cerebral palsy. Her research is supported by a combined $8.5 million in funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH).

In one five-year, $2.8 million grant, Quinlan investigates primary afferent depolarization (PAD) as a contributor to altered movement in cerebral palsy. PAD is a mechanism that adapts reflex response—in other words, the knee-jerk response tested in a typical doctor’s visit to different states of alertness. In cerebral palsy, where a spastic or exaggerated reflex response is present, maladaptive PAD may be at fault. She also studies the use of a potential over-the-counter device, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation, as an accessible and non-invasive treatment to reduce muscle stiffness in those with cerebral palsy. In another five-year grant, Quinlan is researching the role of serotonin on those with cerebral palsy in collaboration with Marin Manuel, assistant professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences and Ryan research assistant professor of neuroscience.

Partnering with kinesiology and fellow Ryan institute faculty Christie Ward- Ritacco and Susan D’Andrea, Quinlan is studying how gait can act as a potential biomarker for those with ALS. Furthermore, Quinlan is collaborating with researchers at Johns Hopkins University to study a genetic mutation present in certain forms of spinal muscular atrophy that contributes to a leaky blood-brain barrier. This work was recently published in Science Translational Medicine.

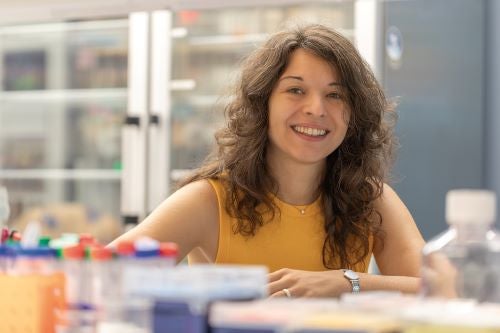

Another of the Institute’s leading scholars is Claudia Fallini, an assistant professor of cell and molecular biology and Ryan research assistant professor of neuroscience. Her recent work focuses on a group of proteins that is rarely studied, but which play an important role in cell function and survival: the linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) complex.

Ryan Research Assistant Professor of Neuroscience

“I’m a person who likes to see things,” says Fallini. “Cell biology is very visual. You can see the inner workings of a cell and how all its components—proteins, organelles, DNA—interact to allow cells to function in an organized way.”

Fallini’s lab has observed that the LINC complex becomes compromised in patients with ALS. This disrupts the cell’s critical ability to adapt to its surroundings. She asks, “If you can define how disruptions of this mechanism might lead to degeneration, can we pinpoint specific places where we could intervene and prolong the survival of the neuron?”

Her observations raise questions, not only about how LINC complex dysfunction contributes to disease, but also if it might serve as a therapeutic target. Fallini also studies whether the LINC complex is involved in the heightened risk of Alzheimer’s disease for people after ischemic stroke, which blocks blood flow to the brain.

“Studies have shown that risk of Alzheimer’s disease can double after ischemic stroke,” she says. “One of our questions is to look at whether changes we see in the pathways affected by the LINC complex after stroke make surviving brain cells more vulnerable to factors linked to Alzheimer’s disease or age-related stressors.”

The Institute’s overall vision, however, is what truly grounds Fallini. “Sometimes people get lost in the details of the mechanisms and lose track of the purpose of why this work matters,” she says.

I was drawn to the Ryan Institute because of the therapeutic focus. For ALS, I want to try to help people who have no cure, no therapeutics, nothing to improve quality of life or their survival.Claudia Fallini

That same mindset drives not just the Ryan Institute and its faculty, but URI’s overall prioritization of neuroscience. URI’s Interdisciplinary Neuroscience Program (INP) offers undergraduate and graduate degrees on multiple neuroscience tracks—cementing the University’s status as a regional biomedical science hub. The program began with three students in the first semester and has now expanded to include more than 150 students.

Many URI neuroscience faculty and students collaborate with nearby biotech, pharmaceutical, and clinical entities in Rhode Island and Massachusetts, as well as medical and academic institutions across the U.S. and overseas. The Ryan Institute has brought in more than $45 million in federal and private funding in the past five years to research neurodegenerative diseases. However, those funds cannot be used for buildings. The partnerships forged by the leadership of the Ryan institute between academia, industry, and government are crucial to our collective success. The research being conducted by this team will resonate in the lives of people for decades to come.