KINGSTON, R.I.—Every morning, University of Rhode Island junior Alec Mauk checks emails and then sits before a microscope, staring at myriad organisms in water samples taken from Greenwich Bay. Before him is a book to help identify species of invertebrates with which he is unfamiliar.

“It has been my bible,” admits the Westport, Mass. native.

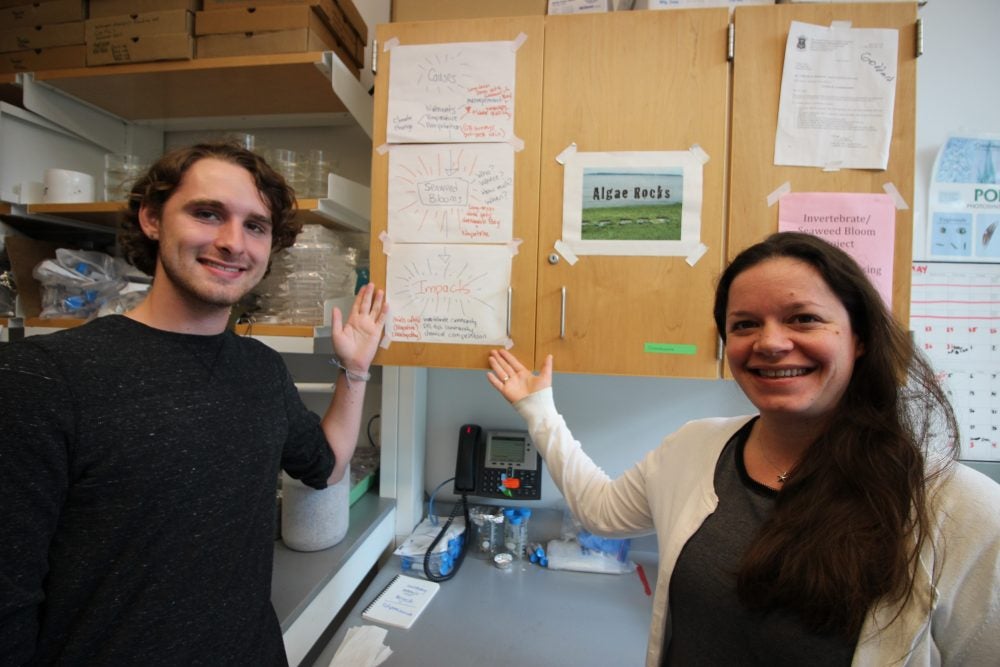

Mauk, a marine biology major, has been working under mentor Dr. Lindsay Green-Gavrielidis, a post-doctoral researcher in URI’s College of Environment and Life Sciences, since last year to research the impact of seaweed on invertebrate species living in the ‘benthos,’ or community of organisms which reside on the seabed. Dr. Niels-Viggo Hobbs, an adjunct faculty member in the Biology department at URI and a postdoctoral researcher for the Environmental Protection Agency, has been the invertebrate animal expert helping Mauk identify invertebrates.

The question concerning the researchers is: are higher accumulations of loose seaweed harmful to these benthic communities?

“Invertebrates feed on and off seaweed, or use it as habitat,” explains Green-Gavrielidis. “In places like Greenwich Bay, however, you will see seaweed form a physical coating that can smother the surrounding benthic communities, which creates issues for species that need oxygen.”

Mauk and Green-Gavrielidis explain that scientists currently measure a seaweed ‘bloom’ to be any accumulation greater than 5mm. SURF student and mentor are not convinced such a measurement accurately measures the impacts of seaweed on the surrounding environment.

“Where is the tipping point?” says Green-Gavrielidis.” I am skeptical that 5 mm is a threshold where it goes from being a positive to a negative thing, so we are trying to see if that plays out in Narragansett Bay.”

Having collected samples from Greenwich Bay last summer of sediment and water impacted by seaweed blooms, as well as those clear of significant seaweed cover, Mauk is now in the process as a SURF student of cataloging the species contained in each sample so that preliminary conclusions can be drawn.

“This past school year, me and a few other undergrad assistants sorted out all of the invertebrates,” he explains. “This summer, I have been chugging away, identifying what those species are so we can get the community fully fleshed out.”

“I hope that once we start analyzing the data, there will be some trend I will be able to notice or something we can build upon.”

Green-Gavrielidis notes that she has concealed the location of the specific samples until after Mauk has done his initial species identifications. Mauk says the practice has been helpful in keeping his initial observations as unbiased as possible.

“It is not a deliberate bias that people have, but subconscious,” says Green-Gavrielidis. “If you have an expectation for what you will find and are not seeing it, you might question yourself or try a little harder to find something.”

Mauk, who is thinking about applying to graduate school, is more comfortable now working in a lab environment, making sure that his data and observations are scientifically sound, as the SURF program comes to a close.

“I am adding a lot of tools to my toolbox.”

Mission: Oyster Study

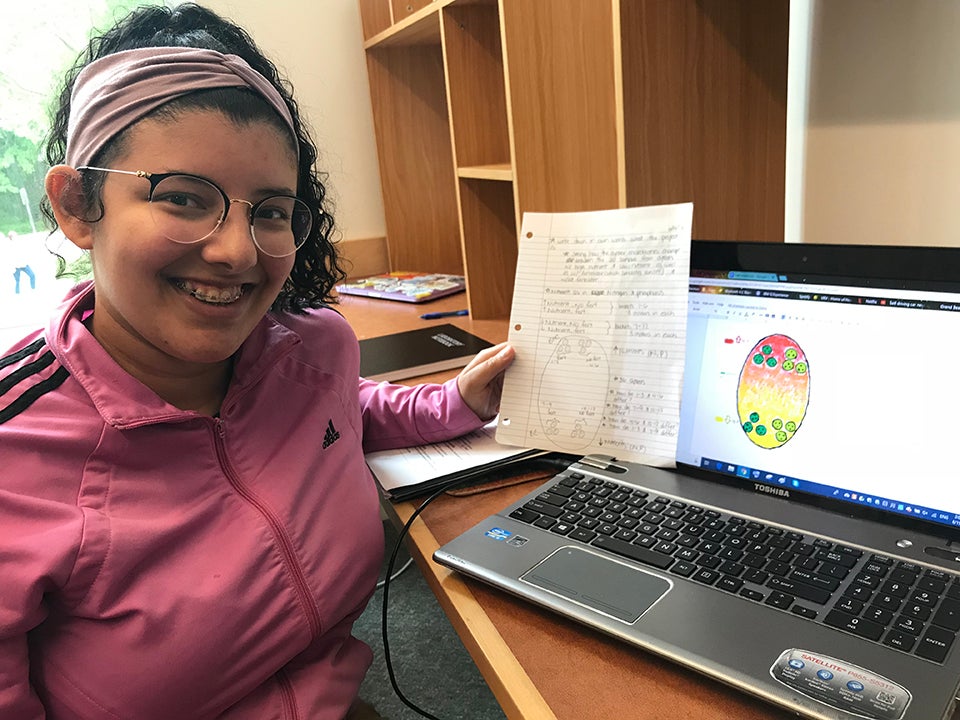

For URI senior Dana Rojas, the oyster was a species she knew very little about. Over the past several weeks, the SURF student has gained a much greater knowledge of the bivalve and its health as she learns about their habitat in Narragansett Bay and Rhode Island’s coastal ponds.

“I didn’t know much about oyster farms,” explains the molecular biology major. “I always knew that oysters were important, but I am learning more about how they are now.”

In order to figure out some of those issues, Rojas is working under mentors Dr. Marta Gomez-Chiarri, professor and chair of the Fisheries, Animal and Veterinary Sciences department at URI, and Ph.D student Rebecca Stevick, to examine samples of adult oyster tissue impacted by high and low levels of exposure to nitrates and phosphates, chemicals which are typically found in fertilizers.

“We have 6 buckets of oysters with fertilizer, which simulates run-off, and 6 buckets without as a control,” says the Providence resident. “We will be seeing how the microbes in these oysters differ.”

Rojas has learned how to analyze DNA sequences to identify the microbes which may be impacting the oysters. Being in the lab every day, says the URI senior, means feeling more like an adult, even though the SURF experience is better than a regular job.

“Seeing actual oysters and the ecology stuff I am learning now, it is really cool,” says Rojas. “I just completed my first four years, and it is nice to keep myself doing something new.”

Although she is still unsure of the right career path, Rojas has found that her SURF experience helps to make that decision clearer.

“I can’t see myself studying anything other than cell and molecular biology, but I wanted to gain more insight into what I wanted to do, to see if I like being a lab researcher or not. You have to do it to find out.”

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.