SMITHFIELD, R.I.—When Krystyna Kula was a child, she learned first-hand about Narragansett Bay as a volunteer for Save The Bay. Now, the Smithfield native is spending her summer with Bryant University’s Dr. Christopher Reid, studying how micro-organisms transport carbon and other nutrients into larger species.

“We don’t really know right now how carbon moves through the food chain,” explains Kula, a Biology major at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana. “We are feeding isotopically labeled carbon to yeast, which will then be fed to a dinoflagellate plankton. That will help us see how carbon moves through the food chain.”

Kula has collaborated with SURF mentors Dr. Tatiana Rynearson and Dr. Susanne Menden-Deuer, to complete her research on lipids at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

The end goal, says Reid, is to better understand how hydrocarbons, called ‘lipids,’ travel through ingestion from the tiniest zooplankton to economically important species such as shellfish, a process known as ‘trophic upgrading’.

“We are right at the bottom, looking at the early stages of the food chain,” says the associate Professor of Science & Technology at Bryant. “We are examining one unicellular predator in Narragansett Bay which eats algae and asking, are they starving or well-fed?”

He adds that understanding how many lipids the dinoflagellate consumes could lead to using the species as a biomarker for chemicals appearing in the bay.

“That is the pie in the sky goal,” he admits.

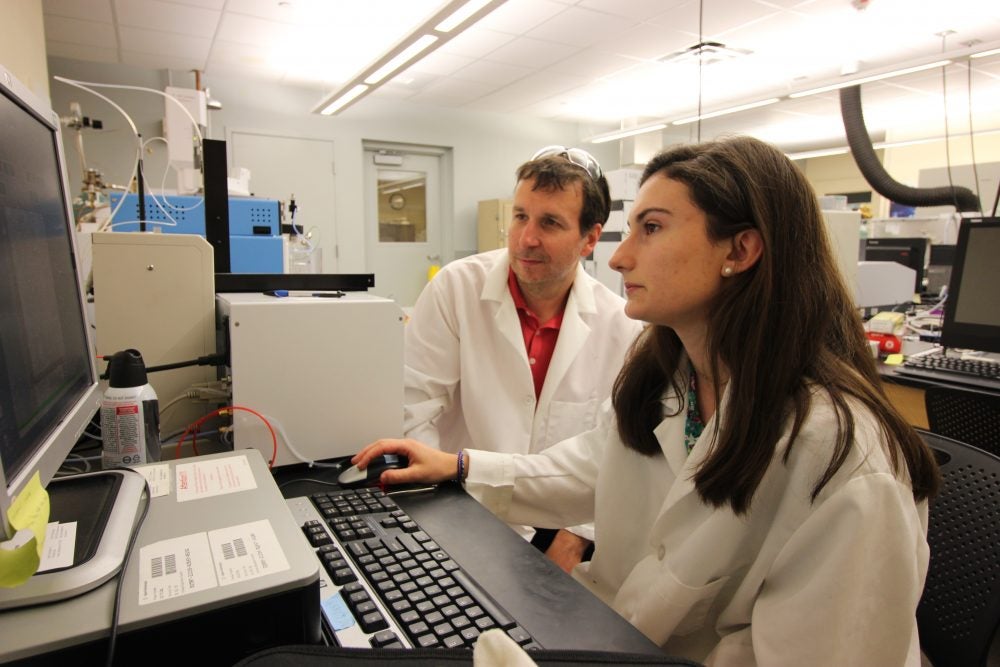

For Kula, her first experience in a research lab has been much different from the classroom, learning to use equipment such as a gas-chromatography machine to separate and identify chemicals from water samples.

“In class, you learn for the test and forget about it, but this is something that has an actual application to the real world,” she says. “This experience is a good look at how it would be if research was my job day-to-day.”

Reid, who hosts as small group of undergraduate and graduate researchers at Bryant, tries to foster a friendly working environment through which students can learn together.

“I was a little bit nervous coming in,” admits Kula, who will be a sophomore at Notre Dame this fall. “But everyone was really welcoming and helping me with how everything works in the lab.”

Although she has a few years before deciding on graduate school, Kula knows the experience will serve her well.

“I wanted to take this summer and figure out if this was something I could do every day.”

Plastics unseen

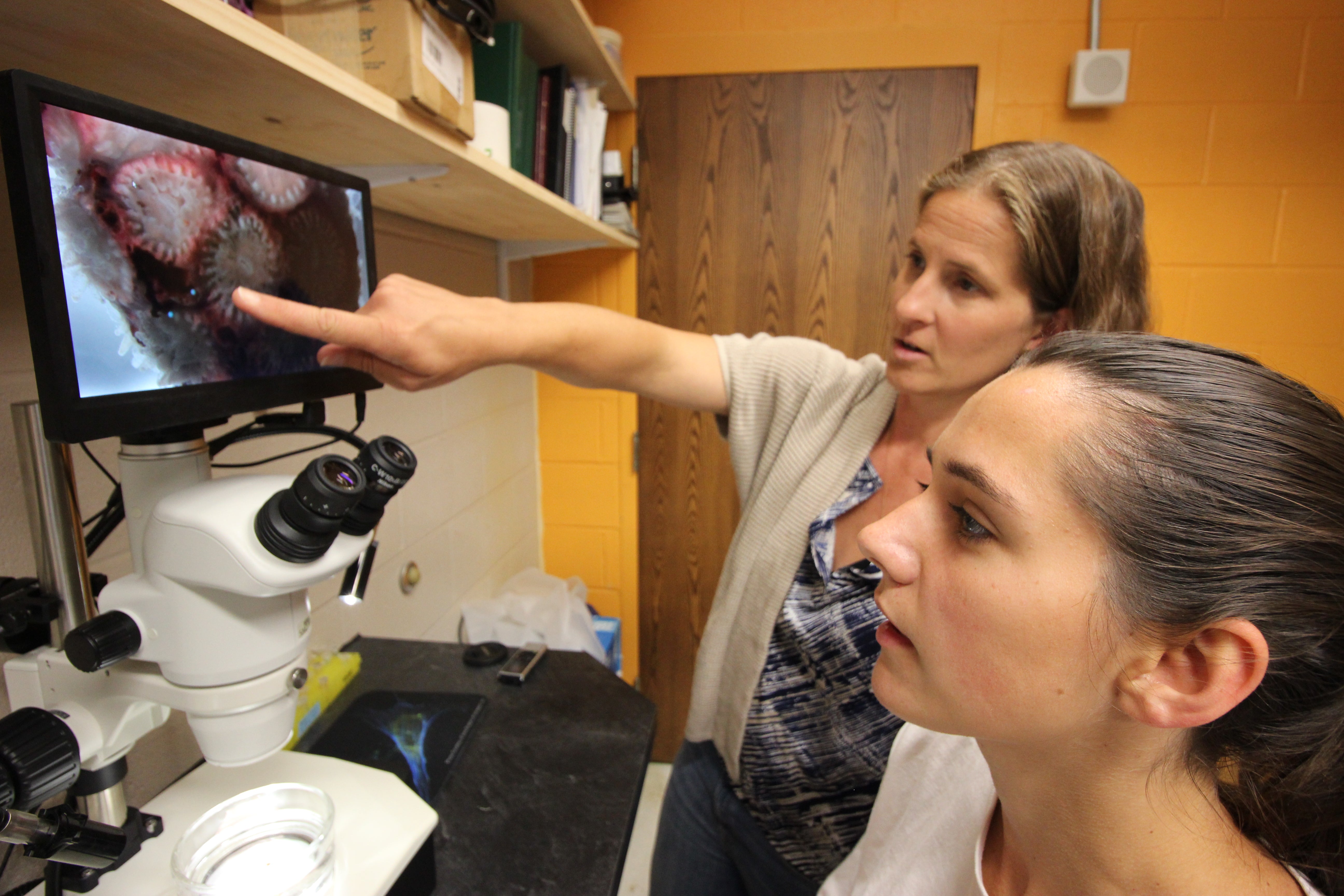

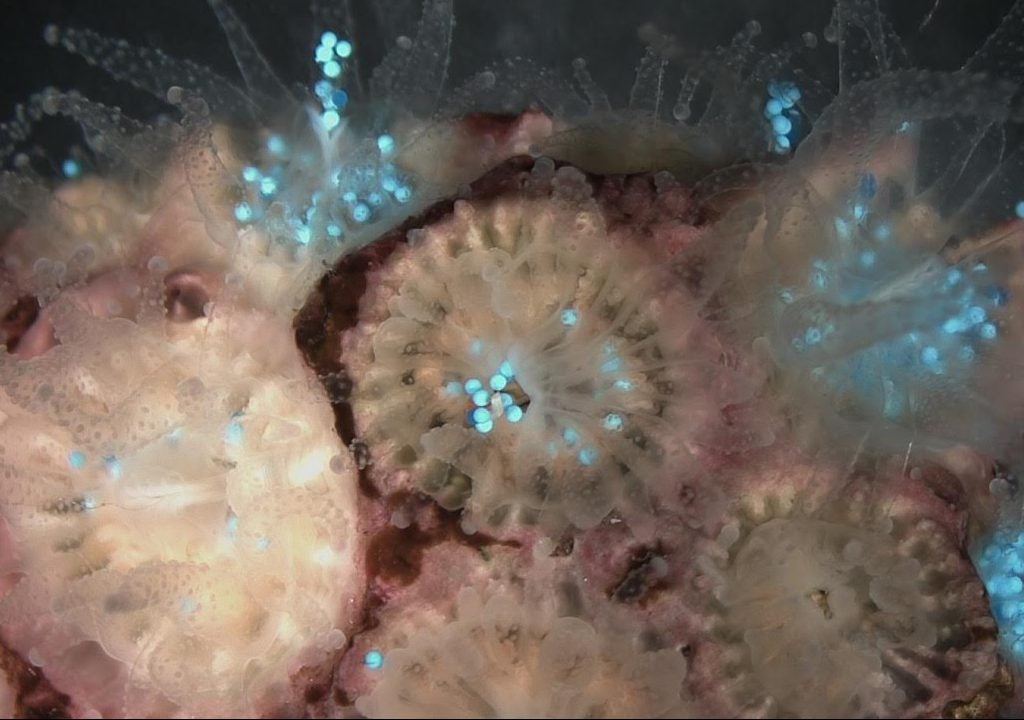

Roger Williams University junior Leah Hintz does not mind sitting in front of the microscope, so long as her specimen, a species of coral found in the waters off Fort Wetherill in Jamestown, does what she hopes: ingest microplastic beads.

“Sometimes the coral don’t cooperate,” says Hintz with a laugh. “A few

times we have been sitting here for three hours and nothing happens. I’ll think, ‘this is too long’ and wait another hour, but that is science.”

But why is Leah, a Fairfield, Conn. native, feeding the tiniest plastic particles to this coral, named Astrangia poculata? To discover how one of the world’s most concerning environmental hazards is affecting food webs at the microscopic level.

“Plastics in the ocean are weathered down and become microplastics,” explains the Roger Williams student. “They are everywhere – every time we wash our clothes in the washing machine, plastic microfibers shed from our clothing and wash into the water supply. Eventually, these microplastics are ingested by animals like filter feeders and get transferred through the food web into species that we eat. It is not good.”

“It’s a concern for us because of human seafood consumption, but it’s also a threat to marine life – nutrition of the animals is impacted by microplastics,” adds Dr. Koty Sharp, Leah’s mentor and assistant professor of Biology at RWU. “If your gut is filled with plastic instead of proteins and carbs and fats, there’s little in your gut to provide energy for growth and reproduction.”

By measuring how many microplastics the local coral ingests, scientists are using the species as a biomarker indicating plastic levels in waters which may seem clean, especially in urban areas.

As an assistant professor of Biology at RWU, Sharp has been impressed by Leah and her fellow undergraduate researchers as they developed novel ways to measure how microplastics affect species such as Astrangia.

“I think that the most important thing to teach our students is that when you work together, your science is better,” she asserts. “This group has had to design their methods from scratch – they’re figuring out original methods for how to deploy equipment and run experiments. These guys work as a team.”

Leah and her colleagues, for example, needed to figure out a way to trap microplastic beads within the waters off Fort Wetherill for a period of time so that local seawater microbes would grow on them. Their solution was simple; small piece of PVC pipe wrapped on both sides by a nylon mesh. The SURF researchers could thus bring the beads covered in microbes back into the lab and examine how microbes on the surface of microplastics influence how much plastic Astrangia eats.

Throughout the 10 weeks of SURF, Leah has exhibited a unique passion for research, and will continue studying coral in Bermuda this fall.

“She is my Ms. Positivity in the lab,” laughs Sharp.

Written by Shaun Kirby, RI C-AIM Communications & Outreach Coordinator.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.