BRISTOL, R.I.—Roger Williams University senior Colby Masse, leaning on a lab counter in the Marine and Natural Science building, describes Narragansett Bay as a ‘sink’ for chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Along with fellow SURF student Lyndsay Marlowe, he is working under Dr. Stephen O’Shea to discover the process by which these chemicals are deposited into the bay’s sediment, and also transformed into other chemical compounds which could prove harmful to the environment.

“CFCs were used in aerosols and refrigerants and were non-carcinogenic, but scientists started to notice there was a big gaping hole in the ozone, and they were contributing,” explains Masse, a biochemistry major from Williamstown, Mass. “Countries regulate them now, but they can still affect the ozone years after being released. That is why we see them in the ocean sediment.”

The ozone protects the Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays of the sun, and its depletion causes both atmospheric and ocean temperatures to rise, ultimately impacting ecosystems throughout the globe, including Mount Hope Bay where the students are gathering samples.

Masse and Marlowe are now testing potential techniques to better understand how CFCs are transformed in sediment and ocean water, and whether their chemical makeup changes for better or worse in the process.

“We are looking at individual compounds of CFCs and how they get converted in the ocean ecosystem through select bacterial or chemical processes,” adds O’Shea, professor of Chemistry at RWU.

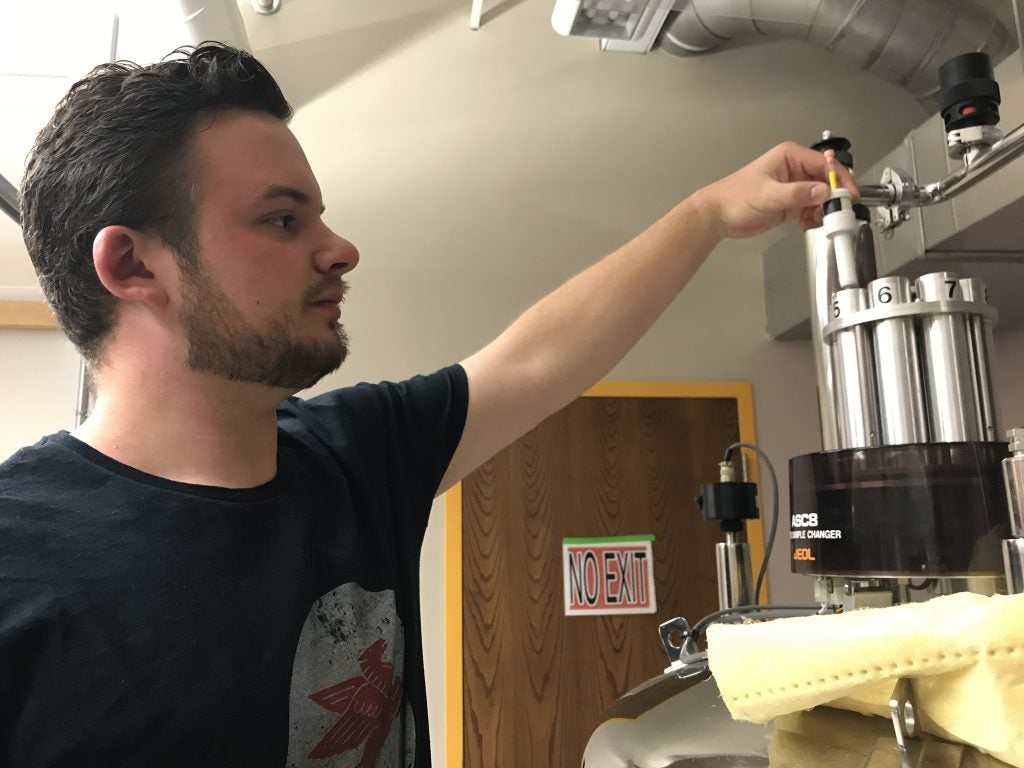

There are challenges, however, as the SURF students learn to use complex equipment and discover that scientific inquiry is much a process of trial-and-error.

“Getting all of the tests to work properly is a challenge,” admits Marlowe, a junior at Roger Williams studying chemistry who hails from Tewksbury, Mass. “There’s a lot of preparation and, when something is not working, a lot of troubleshooting.”

“We are looking at CFCs and organisms in anaerobic environments, so it is a struggle to keep our samples unexposed by oxygen,” adds Masse. “We try to keep samples in an inert gas like argon, but it is tough when you are doing live tests. They take multiple hours.”

For O’Shea, the experience is one uniquely available to students in a small laboratory like that housed at RWU.

“They are not giving samples to a technician, but are doing hands-on experimentation themselves,” he emphasizes. “The lab and instruments are robust enough for research, the data collected from which is publishable. Through SURF, students can set up experiments and follow them all the way through uninterrupted by classes coming in and out.”

Many SURF projects are single steps in a larger research program, and O’Shea’s work on CFCs is no different. Marlowe and Masse know the research they conduct will be crucial for future SURF students.

“I like the variability of the research,” says Marlowe, who hopes to continue her work with Dr. O’Shea into the school year. “Knowing that I am contributing to something a lot bigger definitely makes me excited to see what results come of it long-term.”

“A lot of the time when you go to research presentations, you sit through talks and at the end, you ask, ‘ok, who cares?’” notes Masse, who is applying to become a physician’s assistant. “They don’t know how it contributes to larger science. Here, we do. Figuring out all these different applications for our work, that is why it is rewarding.”

Written by Shaun Kirby, RI C-AIM Communications & Outreach Coordinator

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.