WARWICK—Some days, SURF students Ana Nimaja and Marcos Figueroa travel along the rocky shoreline only to find bay users who want nothing to do with them. On a good day, however, coastal visitors open up about their experiences along Rhode Island’s coast, detailing the bay’s significance beyond scientific research and tourist dollars.

“Catching people off-guard has been our specialty,” laughs Nimaja, a senior Political Science and Spanish major at the University of Rhode Island.

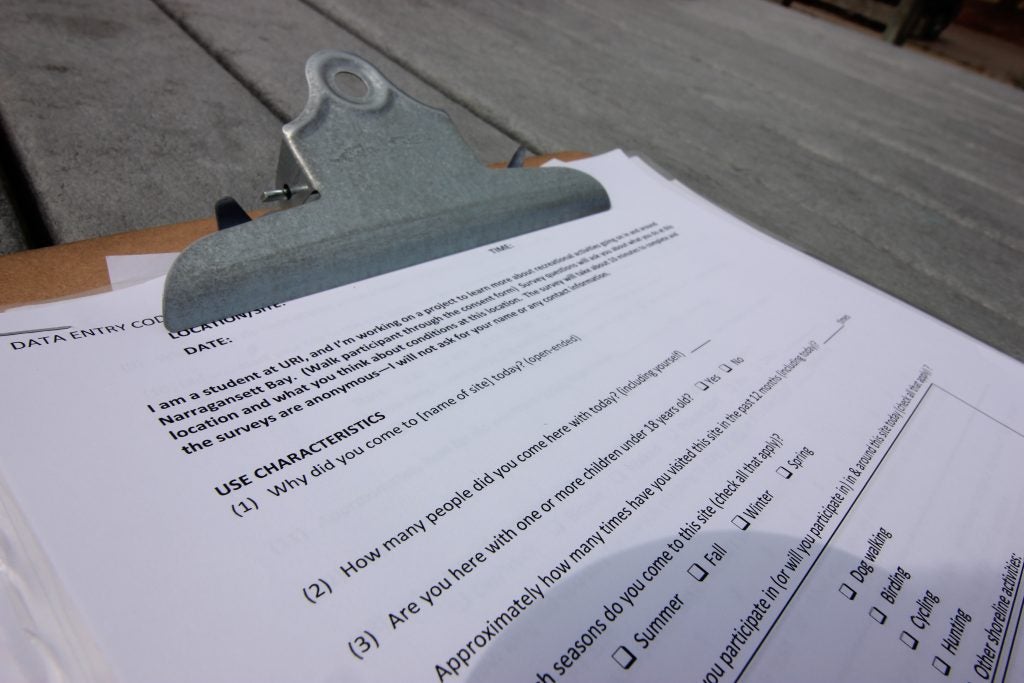

Nimaja and Figueroa have teamed up with SURF mentors Dr. Tracey Dalton and Talya ten Brink, as well as a team of social scientists from Rhode Island College, the University of Rhode Island and the Environmental Protection Agency, to conduct surveys of coastal users about how they interact with coastal areas in and around Narragansett Bay.

“The students are working on two different projects, an intercept survey on recreational use around the bay where we visit about 20 different sites,” explains ten Brink, a Ph.D student in Marine Affairs at URI. “The other is interviewing recreational fisherman at four sites in Warwick.”

Reaching out to the Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) for input, ten Brink was asked to learn more about how millennials and minority groups utilize the bay’s coastal resources as the state organization gathers data for a new Narragansett Bay planning initiative.

“I have always been interested in the needs of people who have two jobs and don’t have time to speak at community meetings,” she emphasizes. “I think it is really important to capture the voices of bay users who access the coast, a natural and healthy environment.”

Enter Nimaja and Figueroa, URI seniors majoring in Political Science and Economics, respectively. Both students speak Spanish fluently and are double majors in the language, a crucial qualification when surveying Hispanic coastal visitors. They did, however, face a big challenge in gathering substantive information through interviews, learning the skills of qualitative data collection.

“Sometimes people don’t want to talk. They’ll grunt at you and you say, ‘that’s discouraging’,” says Nimaja. “But then you have that one Cambodian man who has broken English but is willing to talk and speak about how the bay reminds him of his homeland. It is really great to hear all that.”

Ten Brink and the students have learned the myriad reasons why Rhode Islanders visit the shore, from cancer patients looking for a moment of peace to older residents remembering past beach and fishing excursions.

“I am a huge history buff, and the nostalgia attached to Rocky Point is incredible when you talk to older folks,” notes Nimaja. “You don’t realize how important a place is to somebody until you sit down and talk to them.”

Figueroa has focused on discovering how much Rhode Islanders are investing in order to recreate around Narragansett Bay.

“If you can figure out how far people are willing to travel to a place, you can perhaps understand how much money they are spending in gas,” he says. “You can understand how much the space is really worth to the overall community.”

Once the SURF students’ experience is complete, ten Brink will analyze interviews with recreational fishermen and work with the rest of the research team to analyze visitor survey data. Results from both studies will inform conclusions about Narragansett Bay as a social and economic resource for recreational uses.

“It will be a really long process, but hopefully we can connect with local communities and share these findings directly so that there is more awareness about the importance of coastal areas for minority groups, especially in urban areas like Providence.”

Dalton and ten Brink praised Nimaja and Figueroa for their work in helping to develop relevant survey questions to learn more about visitors to Narragansett Bay. For the SURF students, learning more about the social importance of Narragansett Bay has opened their eyes to new career pursuits.

“It is important for me to understand how the environment can affect sustainability and the overall economy, so it’s made me more curious to explore the field of resource economics more,” admits Figueroa, who plans on applying to graduate school after URI.

Nimaja wants to take a gap year and perhaps teach English in Spain before pursuing a law degree. Although she was initially interested in criminal justice, environmental law is an option she will consider after her SURF work is done.

“When I first read our project descriptions, it sounded very scary because it was all really science-y,” says Nimaja. “I didn’t realize the environment mattered to so many, but having this experience has me really appreciating Narragansett Bay more, and it has definitely impacted my perception of what I can do with my career.”

Written by Shaun Kirby, RI C-AIM Communications & Outreach Coordinator

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.