Professor Kathleen Melanson’s study, funded by $300,000 USDA grant, aims to provide context to ultra-processed food discussion

Ultra-processed foods make up more than half the food average Americans eat. Including frozen and prepared meals, most packaged snacks, desserts and carbonated soft drinks—but also including more innocuous foods—they are often considered the bane of healthy eating, containing little to no nutrition to fuel healthy bodies.

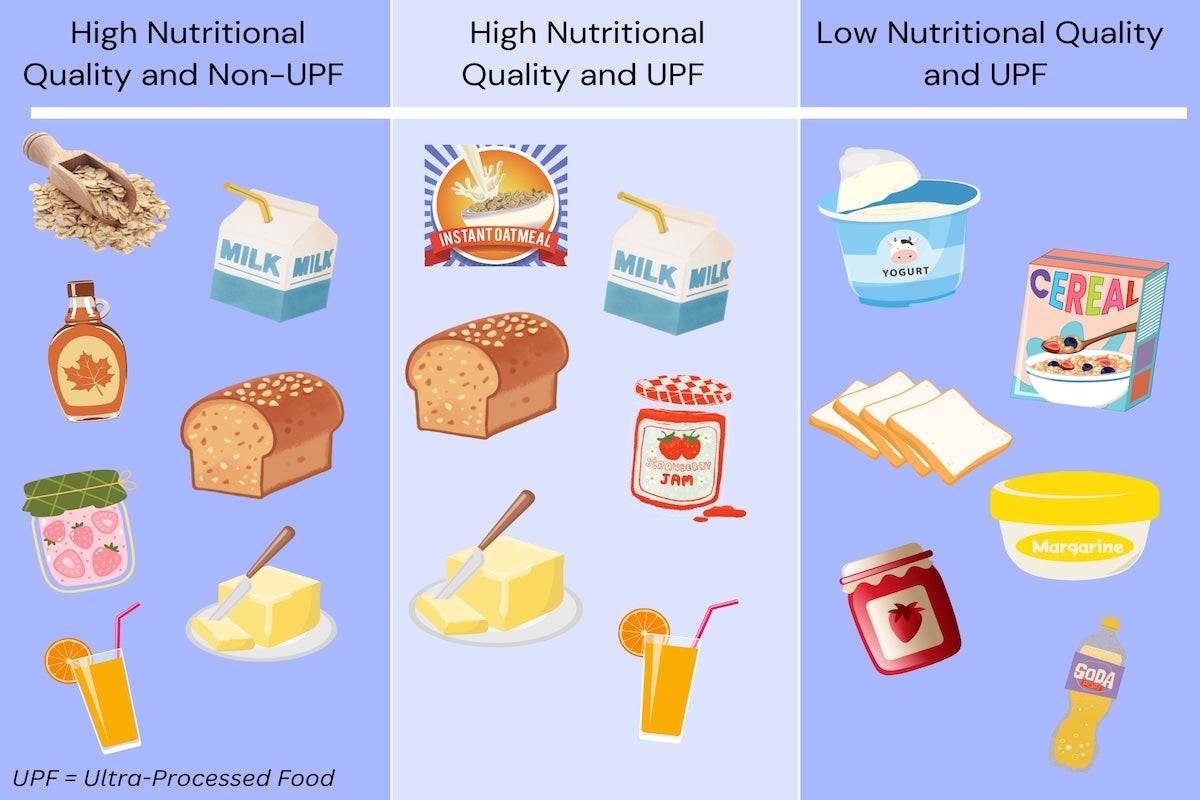

However, “not all processed foods are created equal,” according to University of Rhode Island Nutrition Professor Kathleen Melanson. Evidence to support the assumption that ultra-processed foods are all bad for one’s health is limited, and the nutritional quality of processed foods has not been considered by official U.S. Department of Agriculture dietary guidelines. Melanson, along with Nutrition Department Chair Ingrid Lofgren, aims to help inform the newest guidelines, due out in 2025, as she begins a nutritional study funded by a $300,000 grant from the USDA.

“The classification of foods as ultra-processed is kind of nebulous and confusing,” Melanson said. “Consumers don’t understand what it means, and even researchers are in heated debates about classifying foods according to level of processing. Looking at just the process itself is very unidirectional, instead of considering other features of the food, most importantly the nutritional quality. Researchers tend to pigeon-hole foods, so our study is addressing a broader perspective to categorize food that takes into account not only processing, but also the nutritional quality.”

Ultra-processed foods can include what most refer to as “junk food,” like donuts, potato chips and soda. But “processed food” can mean something as simple as the skin being removed from a tomato before canning, or seasonings being added for taste. It can also mean that some foods have actually been improved nutritionally, such as whole grain breads or cereals that have been fortified with vitamins and minerals. Current nutritional guidelines do not delineate between positive and negative processing.

Melanson is seeking volunteers to visit her lab on the Kingston campus on three separate occasions, during which they will be served test meals to compare. One meal will be “the gold standard” of nutrition—minimally processed food with high nutritional value—and participants will compare it to one meal of highly ultra-processed food with high nutritional quality, and another of highly ultra-processed food with low nutritional quality.

“There are foods in the American food supply within that middle category that are ultra-processed, according to the categorization, yet they’re high in dietary fibers, they provide vitamins, minerals and phytonutrients, protein, essential amino acids,” Melanson said. “These foods also tend to be more affordable and more convenient for consumers who have a tight budget or a tight schedule. We are trying to understand if they are OK compared to the gold standard for people who do have a tight budget or schedule. These are foods that are still high quality, yet convenient and lower cost because of the specific type of processing they have undergone.”

The study is seeking consumer perceptions of ultra-processed foods, while also measuring energy intake, satiety, and eating behaviors using the Universal Eating Monitor to measure the speed different foods are being consumed. Do consumers take in too many calories because they’re eating the tasty, ultra-processed foods too quickly and not realizing they’re getting full? Are they eating too much to compensate for lower nutrition in some processed foods? Researchers will also track participants’ food and beverage consumption for the remainder of each day to assess possible energy intake compensation, and levels of processing of the foods they choose to eat.

Malanson’s lab is also running a companion study about consumer perceptions of foods regarding level of processing and nutritional quality. Adults 18 to 39 are welcome to take a 15-minute online survey to rate whether they think examples of foods are ultra-processed, and whether they think those foods have high nutritional quality, and why. Any adults 18 to 39 interested in taking part in this or the primary study can contact breakfastclubstudy@gmail.com or Melanson at kmelanson@uri.edu.

Together, the studies will shed light on consumers’ perceptions of ultra-processed foods, help inform the USDA, and dispel some misconceptions about processed foods, especially those that fall in the middle, between ultra-processed and organic.

“It would be the ideal if people could grow their own organic food in their own gardens, but most people don’t have the resources or the time for that, so that is an impractical dream,” Melanson said. “Consumers should consider the whole food—yes whether it’s ultra-processed or not—but also what it provides, the pros and cons; not just trying to pigeon-hole it as good food/bad food. There are foods that are obviously at opposite sides—chips, candy, soda—and at the other end is the organic broccoli you grow in your backyard. But it’s the food in between that takes a little more judgment. That’s why the current categorization is not as clear as it should be. It’s the fuzzy middle parts that our study is trying to get a handle on.”