By 2040, the amount of synthetic textiles in our oceans is expected to hit 29 million metric tons. These materials like polyester and nylon partially replace natural fibers like cotton and wool, but they are detrimental to our environment because they don’t disintegrate and decompose. There’s a real need for the work being done by researcher Izabela Ciesielska-Wrobel and businessman Robert Torgerson.

Their joint effort to find answers to the complex challenge of turning trash into treasure is showing promise.

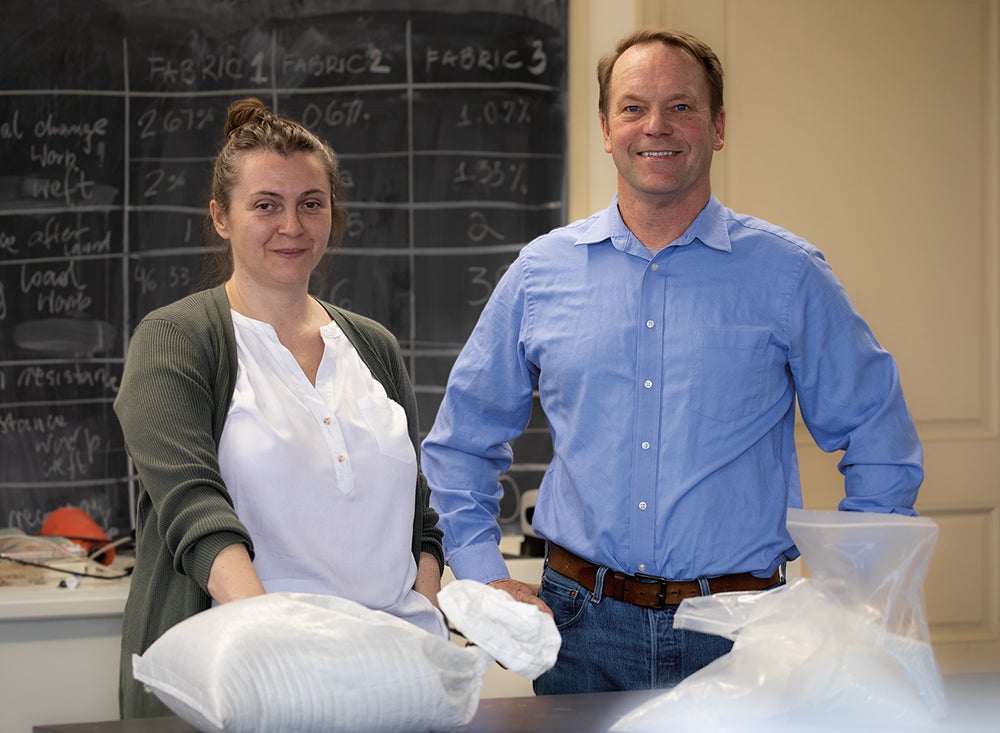

The pair of self-avowed “fiber fanatics” are in the early days of a collaboration to find ways plastic waste can become the foundation for a new type of textile with practical applications. Ciesielska-Wrobel is an assistant professor in the Textiles, Fashion Merchandising and Design department at the University of Rhode Island (URI). Torgerson is the founder and president of Kestrel Innovative Fibers, LLC (KIF), of Wakefield, Rhode Island, produces fibers from recycled plastics harvested from the ocean. KIF’s multi and monofilaments can be used for tennis racket strings, clothing, and sports apparel, among other products.

“From my perspective, textiles are the best materials,” says Ciesielska-Wrobel. “I love textiles. If you have a fishing net that was floating somewhere off California, and someone scoops it up, then decontaminates it, re-melts it, makes pellets, and sends it to me, now I can use this polyester to produce monofilament and multifilament for my textiles.

“I can use these pellets in other ways, too. For example, we can mold larger elements such as bowls for the kitchen, or thin films — all from these plastics. Of course, polyester is not the only raw material floating in the ocean. I already worked with other ocean plastic wastes, such as polypropylene and nylon.”

Currently, the duo is studying converting ocean plastic waste into filament, a textile base. The challenges include the cost of sorting, cleaning and processing waste plastics, as well as the quality and grade of these plastics in the relation to newer, stronger plastics.

“We’re collaborating on identifying recycled plastics,” Torgerson says. “Izabela is evaluating polypropylene, polyester, and nylons. If you take these recycled plastics and make them into a garment, after someone is done with it and throws it out, can it go back into the program and create a circular economy? How many times can that garment be chopped up again into a fiber and made back into a garment? What is that cycle? That’s what we’re looking at.”

“If you take these recycled plastics and make them into a garment, after someone is done and throws it out, can it go back into the program and create a circular economy? How many times can that garment be chopped up again into a fiber and made back into a garment? What is that cycle? That’s what we’re looking at.”Robert Torgerson

Before joining URI, when Ciesielska-Wrobel worked for a private company in Virginia as a research scientist, the enormity and implications of ocean pollution hit home.

Together with Luna Innovations Inc., she obtained a grant from the U.S. Department of Energy to study conversion of ocean plastic wastes into commercially viable textiles.

“To be honest, at that time I had no idea what was happening in our environment,” she says. “I saw images of turtles with plastic straws in their noses, so I stopped using plastic straws. I had no idea that so many creatures die yearly from being entangled in nets or from eating plastic. It completely changed my perspective. First of all, I realized, that I wanted to do something about it. Second, I felt it was my obligation as a researcher to do something about it.”

Ciesielska-Wrobel joined the URI faculty and participated in the URI Initiative, Plastics: Land to Sea, which is meant to foster dialogue and collaboration between the institution’s researchers, non-profit organizations, and the business community for solutions to the plastics pollution crisis.

Ciesielska-Wrobel and Torgerson credit the initiative for their introduction to each other by Kathleen Shannon, assistant to the vice president of research for strategic initiatives at URI.

“She’s a matchmaker,” Ciesielska-Wrobel says. “She knew that Robert and I both talk about conversion technologies.”

Their partnership, while informal, is busy testing materials and ideas.

“Robert brings me samples and says ‘Hey, I have a new material, do you want to see what we can do with it?’” Ciesielska-Wrobel explains. “We test them, see what’s wrong, what wasn’t successful, and what worked. It’s a hands-on collaboration between us.”

To answer the key question, “which types of ocean plastic waste are suitable for textiles?” Ciesielska-Wrobel relies on a new micro compounder with an extrusion line, the only machine like it in New England.

It was obtained for $186,000 from Xplore, a research and development company in the Netherlands. The micro compounder allows mixing different polymer formulations in the melt on a very small scale. Extrusion is a process of pushing the polymer through a small hole, which creates an object with a fixed cross-section profile, which in Xplore case is a circle.

“We can mold larger elements such as bowls for the kitchen, or thin films-all from these plastics.”Izabela Ciesielska-Wrobel

“I have one graduate student helping me work with it,” Ciesielska-Wrobel says. “She’s extruding polyester and high-density polyamides and polypropylene — both virgin and ocean plastic waste derived — comparing the productivity and quality of materials.”

The partnership hopes to foster further study in addition to creating something that can be produced on a large scale.

“With Izabela, I’d like to teach URI students about polymers and plastics along with recycled materials, sustainability, and the circular economy,” Torgerson says. “It would be a great opportunity for kids to learn about it.”

“One day we hope to be able to tell you what specific materials are good for,” Ciesielska-Wrobel adds. “For example, we’ll be able to tell a client: Do you want to make fillers for winter jackets from the material we just tested?”