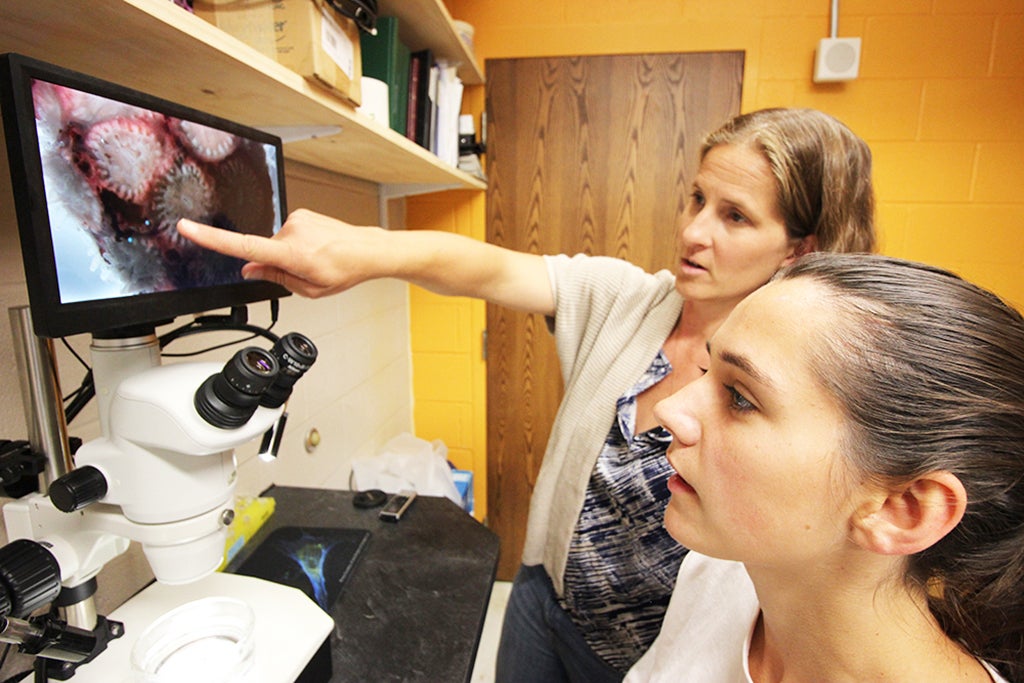

Roger Williams University junior Leah Hintz could sit in front of the microscope for hours, so long as her specimen, a species of coral found in the waters off Fort Wetherill in Jamestown, did as she hoped: ingest microplastic beads.

“Sometimes the coral don’t cooperate,” said Hintz with a laugh this past summer. “A few times we have been sitting here for three hours and nothing happens. I’ll think, ‘this is too long’ and wait another hour, but that is science.”

But why was Hintz, a Fairfield, Conn. native, feeding the tiniest plastic particles to this coral, named Astrangia poculata? To discover how one of the world’s most concerning environmental hazards is affecting food webs at the microscopic level.

“Plastics in the ocean are weathered down and become microplastics,” explained the Roger Williams University student. “They are everywhere – every time we wash our clothes in the washing machine, plastic microfibers shed from our clothing and wash into the water supply. Eventually, these microplastics are ingested by animals like filter feeders and get transferred through the food web into species that we eat. It is not good.”

“[Plastics] are everywhere. Eventually, these microplastics are ingested by animals like filter feeders and get transferred through the food web into species that we eat. It is not good.”Leah Hintz, SURF undergrad

“It’s a concern for us because of human seafood consumption, but it’s also a threat to marine life. The nutrition of the animals is impacted by microplastics,” added Dr. Koty Sharp, Hintz’s mentor and assistant professor of biology at RWU. “If your gut is filled with plastic instead of proteins and carbs and fats, there’s little in there to provide energy for growth and reproduction.”

By measuring how many microplastics the local coral ingests, scientists are using the species as a biomarker indicating plastic levels in waters which may seem clean, especially in urban areas.

Hintz and her colleagues also became scientific troubleshooters, figuring out a way to trap microplastic beads within the waters off Fort Wetherill for a period of time so that local seawater microbes would grow on them. Their solution was simple; a small piece of PVC pipe wrapped on both sides by a nylon mesh. The SURF researchers could thus bring the beads covered in microbes back into the lab and examine how those microbes, together with the plastics, impact the health of Astrangia.

Sharp was impressed by Hintz and her fellow undergraduate researchers.

“I think that the most important thing to teach our students is that when you work together, your science is better,” asserted Sharp. “This group has had to design their methods from scratch – they’re figuring out original methods for how to deploy equipment and run experiments. These guys work as a team.”

Since the summer, Hintz has pursued her enthusiasm for oceanic research, studying coral in Bermuda this past fall.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.