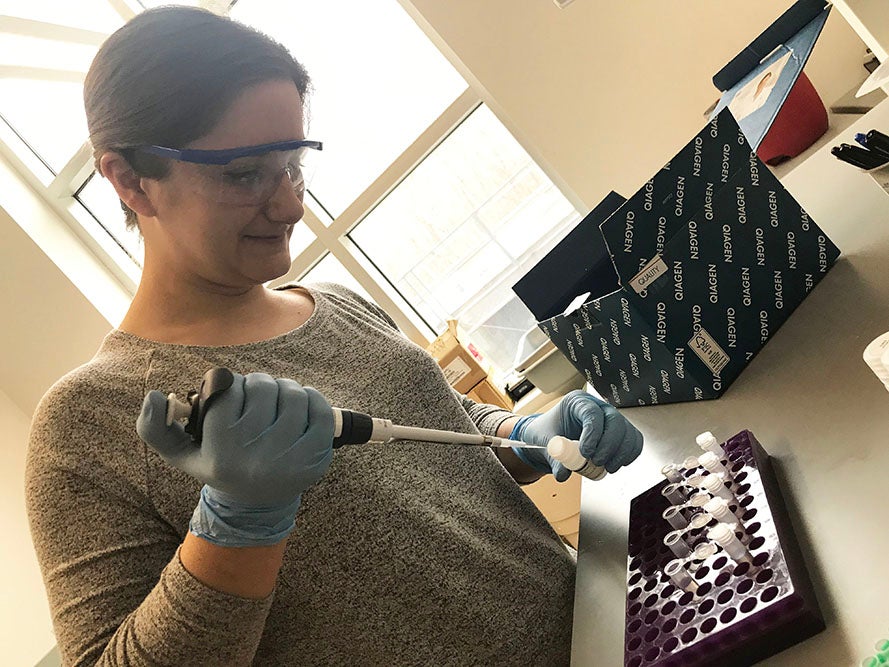

For the past four years, RI C-AIM and University of Rhode Island graduate student Rebecca Stevick has been up close and personal with a staple Rhode Island seafood species: oysters. Now, the fourth year doctoral student has co-authored her first paper on how bivalves can be used as models for human health.

The article, “From the raw bar to the bench: Bivalves as models for human health,” appears in the March issue of the journal Developmental and Comparative Immunology. Stevick’s doctoral advisor, Dr. Marta Gomez-Chiarri, and Dr. Ying Zhang, both professors at URI’s College of the Environment and Life Sciences, are co-authors, along with researchers from across the globe.

“Although no novel research went into the paper, as a review article I think it is important to step back and ask how current research fits into the greater scheme of things,” explains Stevick. “It is fitting that this is my first publication because my undergraduate degree is in biomedical engineering.”

“Even though we tend to be scared of the word ‘microbiome,’ bacteria can be good. Oysters filter water, help with shoreline protection, and provide habitat for other species, so it is important to study what they are doing to help the bay.”Rebecca Stevick, C-AIM graduate student

As part of her C-AIM research, Stevick is examining how microbial communities, or ‘microbiomes,’ can help or hinder oysters as they fight against diseases and environmental changes. The research has the potential to shed light on how other species, such as humans, respond to harmful bacteria or rely on certain bacterial species to fight infection and disease.

“Even though we tend to be scared of the word ‘microbiome,’ bacteria can be good,” says Stevick. “Oysters filter water, help with shoreline protection, and provide habitat for other species, so it is important to study what they are doing to help the bay.”

For example, Stevick has been researching the interaction of oysters and their microbiomes when treated with Bacillus, a probiotic bacterium found to prevent disease in larval oysters. Working at Roger Williams University’s Luther H. Blount Shellfish Hatchery, Stevick and Gomez-Chiarri were part of a team performing hatchery trials to see how young oysters respond to the probiotic that’s similar to what is commonly found in yoghurt.

“We would spawn the oysters and place them into their tanks, then study how they grew and how their microbiomes changed for the first 12 days of their lives,” Stevick explains. “We would see if the Bacillus probiotic was protecting the oysters against disease, and look at what other bacteria was helping as well.”

Stevick, who is fully funded by a NSF Graduate Research Fellowship, is in the final year of her doctoral degree. Her thesis is incorporating all of her work on oysters, including C-AIM research.

“We know that bacteria and plankton are very important to ocean processes and biogeochemical cycles, but on the grand scheme of things, we know very little about how they are involved in the oyster microbiomes,” she says about her work. “I am fascinated by how bacteria allow oysters to do the ecosystem functions that we love them for!”

Funded by a $19 million grant from the National Science Foundation through the Rhode Island Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research (EPSCoR), and also a $3.8 million state match, RI C‑AIM is a collaboration of engineers, scientists, designers and communicators from eight higher education institutions across the state, with the University of Rhode Island as lead, developing a new research infrastructure to assess, predict and respond to the effects of climate variability on coastal ecosystems.

For more information about RI C-AIM, visit www.uri.edu/rinsfepscor.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.

RI NSF EPSCoR is supported in part by the U.S. National Science Foundation under EPSCoR Cooperative Agreements #OIA-2433276 and in part by the RI Commerce Corporation via the Science and Technology Advisory Committee [STAC]. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. National Science Foundation, the RI Commerce Corporation, STAC, our partners or our collaborators.