The Undergraduate Research in Science and Engineering (URISE) program offers undergraduate students an early pathway into research, connecting them with faculty mentors across the College of Engineering and other science disciplines. Designed especially for first- and second-year students, URISE helps you explore research, build new skills, and become part of a collaborative, inquiry-driven community.

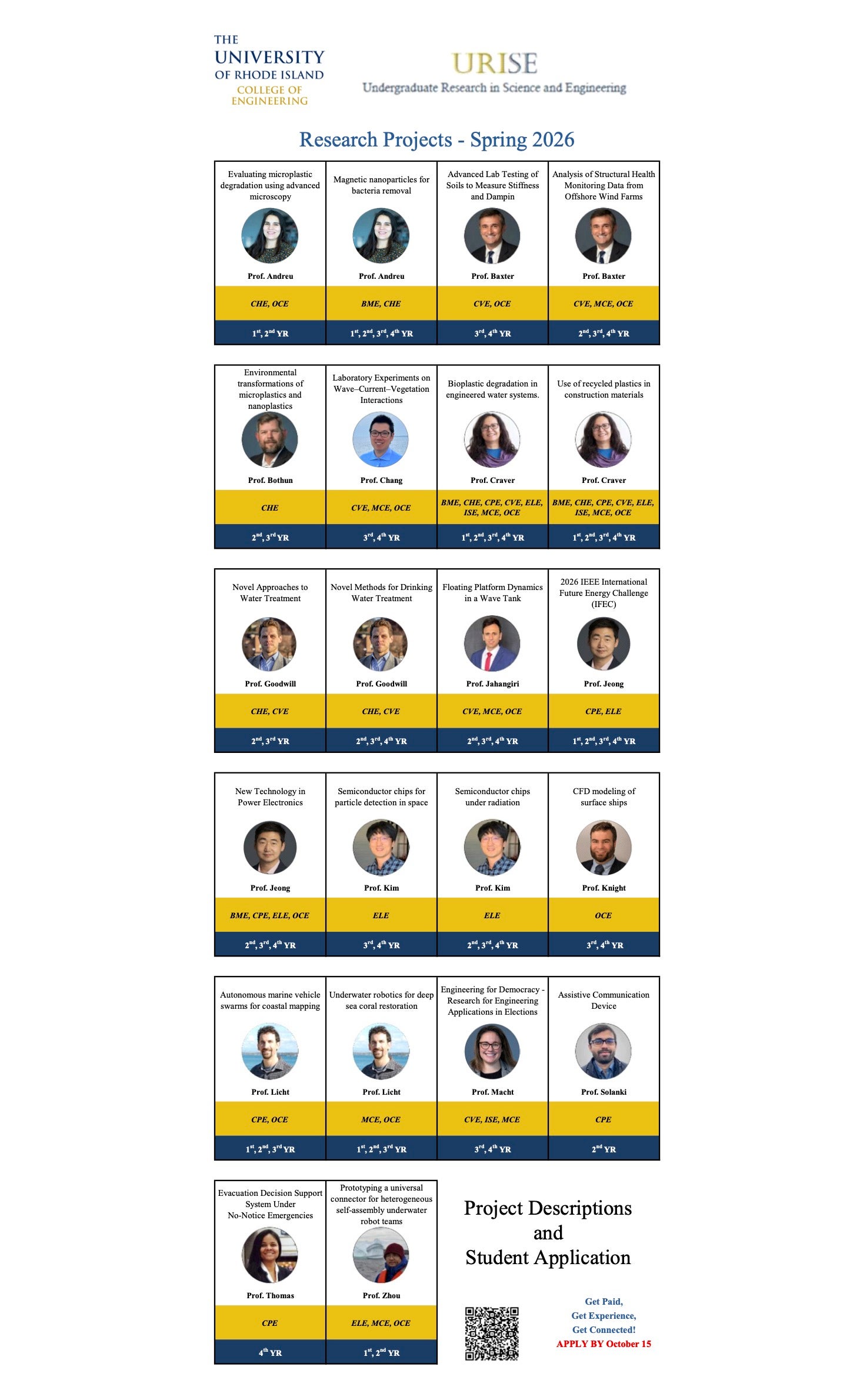

Students selected for URISE work directly in faculty research labs for 5–10 hours per week during the academic year, with funding provided by the College of Engineering. Projects span a wide range of disciplines – from sustainable materials and robotics to biomedical innovation, cybersecurity, and environmental engineering.

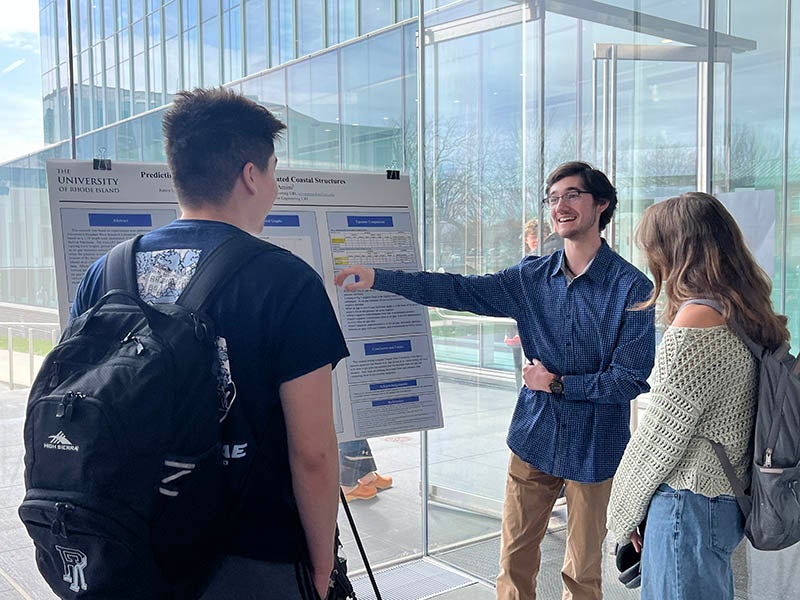

In addition to gaining hands-on experience, students develop relationships with faculty, strengthen their academic and professional goals, and learn how to communicate their work effectively. All URISE participants present their research at the Research Showcase during E-Week, gaining experience in scientific communication and presentation.

Interested?

If you’re interested in research and ready to explore what’s possible, we encourage you to apply! Check out the flyer below for this semester’s available research projects and link to the application.

If you have questions or want to learn more, please contact Rosetta Spino, Student Success Coordinator.