Industrial engineers research complex processes, systems, or organizations and suggest ways to make them better, faster and more sustainable.

The challenge

During the 2016 general election in Rhode Island, significant delays in the voting process were reported at some precincts, including East Providence, Jamestown, Pawtucket, Providence and Warren. In some cases, it took more than two hours for people to cast their ballot. According to the Presidential Commission on Elections Administration (PCEA), a voter should not have to wait more than 30 minutes.

This prompted Secretary of State Nellie M. Gorbea to convene a task force in February 2017 to investigate the cause of the delays, among other concerns. The group, comprised of state and local elections officials, and Rhode Island voters, was instructed to review pre-election, election day, and post-election processes.

Tapping URI’s expertise

Gorbea reached out to URI’s College of Engineering for an industrial engineering professor who would be willing to speak to the task force at one of its meetings.

“I was invited to give a brief presentation at the task force’s second meeting on queueing theory and facilities layout planning,” recalled URI Assistant Professor Gretchen Macht. “I showed a lot of images that illustrated how engineers design ways to reduce waiting time for people, such as E-ZPass for high-speed tolling or a fast pass at an amusement park.”

After Macht attended the task force’s third meeting, the group was convinced that she had the expertise needed to identify ways to better structure Rhode Island’s polling precincts.

In a 14-page report that was released in April 2017, the task force officially recommended that the Board of Elections work with Macht to solve some of the challenges that arose in the previous election. Two of the 17 recommendations in the report described how Macht could “implement best practices on queuing theory” and “implement best practices learned from the private sector.”

While Macht was honored and excited to work on the project, she was well aware of how difficult the task would be.

“Every election is unique, making it difficult to plan for the next one,” Macht said. “There are many factors to consider, such as the growth in population, challenges in security, the limited space at some precincts and the possibility that a scanner could jam.”

A public / private partnership

In September of 2017, a budget was approved and Macht was awarded a grant for $226,942 to conduct her research. The grant, named RI VOTES (Voter OperaTions & Election Systems), was funded by the Board of Elections, the Secretary of State’s office, the URI College of Engineering, and The Democracy Fund, which is an independent private foundation.

A combination of technology and expertise

Associate Professor Valerie Maier-Speredelozzi was able to get Simio, LLC to donate a simulation software package for teaching and research in the industrial and systems engineering program and for use on the RI Votes project. Valued at $132,000, the package includes 55 licenses and technical support.

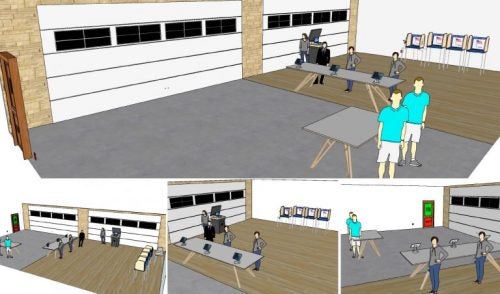

The software enables Macht and her team to create a three-dimensional simulation of any voting precinct in Rhode Island by entering the number of check-in stations, voting booths, scanners and the physical layout of the precinct.

“By using voting data from the 2016 election precincts where everything ran smoothly, we are able to create a baseline trend and compare that to the locations where there were delays,” Macht said.

While technology is being used as a research tool, it also played a significant role in the previous election.

“As challenges in election security arise, technology is being used more and more to ensure that every vote is safe and counts,” Macht said.

Instead of voters having their names looked up in a huge book when they arrive at the check-in table, they will now have their license scanned and be checked-in electronically. However, a change in technology to the “ballot box” has contributed to delays.

“In 2016, Rhode Island started using DS200 scanners to tabulate votes,” Macht said. “They are considered more accurate and more secure. But because of the encryption involved, the scanner takes four seconds per ballot, as opposed to the two seconds the older models needed.”

According to a New York Times article in February, the DS200 scanners are used in 31 states and the District of Columbia.

Multiple precincts in Rhode Island reported scanners that jammed, causing long delays.

“One of things we’re looking into is whether the paper jams were a result of human error or machine error,” Macht said. “Currently, the thought is that the precincts that had especially long ballots, requiring more pages, experienced the most problems.”

Seniors and graduate students in Macht’s ISE | PSY 420: Introduction to Human Factors and Ergonomics course conducted time studies in the fall 2017 semester. They recorded the time it took to check a voter into the polling location, time spent in a voting booth, and time spent at the ballot scanner.

“It gave the students hands-on experience in real-life environments and human factors data collection techniques,” Macht said.

Maier-Speredelozzi had students in her ISE 445 Facilities Planning and Material Handling course work with the Simio software in the spring 2018 semester, in association with Macht’s RI Votes research project.

“Each team of students was assigned a different voting precinct,” Maier-Speredelozzi explained. “They visited the polling location and assessed the space, layout, electricity, parking, and accessibility with respect to the Americans with Disabilities Act. Then they built models of the different precincts using the Simio software.”

Forming a team

When Macht made her presentations to the task force, she brought two URI students with her to take notes, Cherish Prickett of Lilburn, GA and James Houghton of Holtsville, NY.

“They were both highly recommended by their peers and the faculty,” Macht stated. “They were also excited to apply what they’ve learned about industrial and systems engineering to this project.”

Prickett has since graduated, having completed URI’s International Engineering Program. Houghton graduated in the spring of 2017. After working in industry for almost nine months, he rejoined the team in spring 2018.

Nicholas Bernardo, of North Haven, CT, joined the team his senior year. As an undergraduate the project was considered an independent study. As a graduate student, the project serves as his thesis work.

Bernardo and Houghton recently spent four days at a training at Simio’s headquarters in Sewickley, PA.

“Going to the Simio headquarters was an invaluable learning experience for us,” Houghton said. “It gave us the opportunity to learn from one of the original authors of the software.”

The newest member of the team is undergraduate Ahmad Siddiqi, from Lincoln, RI. The mechanical engineering student beat out several other candidates who interviewed for the position.

Siddiqi has completed several 2D and 3D sketches of the precincts and has worked on models using the Oculus Rift virtual reality system.

“Each member of the research team has their own strengths. We have different areas and levels of expertise, but we work well together,” said Macht, who oversees the students’ work in her Sustainable Innovative Solutions (SIS) lab.

Research should help upcoming election process

The RI VOTES project won’t be completed until June 2019, but the November 2018 elections will play a significant role in advancing the research.

“We’ll apply what we have at the time of the 2018 elections and use the results to improve and adapt the models,” said Bernardo. “This can act as a small-scale trial of the tools we have developed.”

The midterm election will provide additional data for Macht’s team to use, even though the turnout is expected to be lower than it is in a presidential election year. Regardless of the turnout, how prepared a voter is also affects the flow of traffic through the voting process.

“Ballots are posted outside of each precinct for voters to read before they enter their polling location,” Macht said. “If a voter is reading the referendums for the first time when they’re in the booth, then it will take much longer before they cast their ballot.”

With the initial task of collecting, entering and processing the 2016 election data complete, the research team is finishing the time-consuming task of making sure the data is accurate and interpreting the information.

The third task is to develop a simulation model that can be applied to any precinct in the state, regardless of population, the number of machines or workers, or the length of the ballot.

Ultimately, the researchers would like their work to result in a more favorable experience for Rhode Island voters.

“We hope to reduce the maximum time a voter spends in a polling location in our simulated models, and then replicate these models in actual polling locations to improve the voter experience,” Bernardo said. “We really want to encourage people to vote by making the experience quick and easy, rather than a seemingly inconvenient obligation.”