By Neil Nachbar

Despite great technological advances in ocean exploration, the world’s most delicate deep-sea species largely remain a mystery.

Until recently, there has been little development in instruments that can be used to safely collect fragile undersea species.

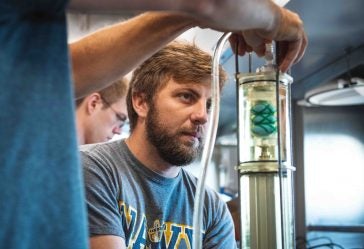

In the last two years, Brennan Phillips, University of Rhode Island assistant professor of ocean engineering, has made significant advancements in the field of soft robotic grippers that can be used to gently grasp these obscure creatures.

Creating and Testing Technology

While on an expedition off the coast of Honolulu, Hawaii from Oct. 12-17, Phillips, two of his students from URI, and colleagues from other universities and research centers, tested soft grippers and other research equipment.

“This mission was focused on technology development for midwater exploration,” said Phillips. “Our primary focus was to experiment with various soft robotic grippers, using a new deep-ocean hydraulic system. We also tested some new miniature deep-sea cameras, which were invented at URI and have a wide range of undersea applications.”

Collaborative Research

The work was conducted aboard the research vessel Falkor, a state-of-the-art, 271-foot oceanographic vessel. Use of the ship and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) SuBastian was provided by the Schmidt Ocean Institute. Collaborating with the URI team were researchers from Harvard University and the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute (MBARI).

“Thanks to the hard work of the science party, the ROV team, and the vessel crew, the trip was a complete success,” Phillips said. “All of our new systems were demonstrated to work at depths of up to 1,200 meters and we are very pleased with the results.”

Student Involvement

The two ocean engineering students from Phillips’ Underwater Robotics and Imaging Laboratory who joined the professor on the trip were Russell Shomberg from Newport, Rhode Island and Brendan Unikewicz from Portland, Connecticut. Shomberg is pursuing a master’s degree and Unikewicz is working toward his doctorate.

“Russ is the lead on the soft robotic drive system we were testing and Brendan is gaining experience with work-class ROV’s,” said Phillips.

Shomberg co-developed the new deep-ocean hydraulic system with Stephen Licht, URI associate professor of ocean engineering.

“We wanted to see our soft robotic hydraulic drive function on an integrated ROV system and test out the new features on the latest iteration of the DEEPi camera system,” said Shomberg. “Our systems performed well, while still having room for improvement.”

During the day, Shomberg and Unikewicz spent their time building and testing equipment. At night, they discussed modifications and improvements to the systems with other members of the research team.

The students found the hands-on experience and interaction with other researchers at sea invaluable.

“The Harvard engineers challenged us to build a drive system to handle their more exotic soft manipulators and the ROV pilots shared with us the challenges of working in a deep-sea environment,” said Shomberg. “That’s something we would have never experienced in a lab.”

Viewing Delicate Organisms

While no species were collected on the expedition, quite a few were viewed. Over the course of six ROV dives, MBARI’s Deep Particle Image Velocimitry system was used to scan a number biological “targets,” including deep-sea jellyfish, ctenophores, siphonophores and glass sponges.

“One of the coolest things we saw was a cubozoan, or box jellyfish, at a depth of 600 meters. These can be extremely venomous,” said Phillips. “We also used our soft robotic gripping system to gently pick up xenophyophores, which are very delicate single-celled organisms that can be very challenging to collect.”

The Next Step

The research in Hawaii sets the stage for an even more ambitious trip next year.

“We have another, longer expedition scheduled onboard the Falkor in late 2020 that will apply these technologies on an exploration mission to a rarely-visited area in the Western Pacific,” stated Phillips.