At URI, neuroscience research activity is concentrated in five major areas: dementia and aging, psychology, biomedical engineering, communicative disorders, and biological sciences. Within these broad areas, researchers at the university are working to answer key questions about Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, Down’s syndrome, epilepsy, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, executive functions, motor speech, spinal cord injuries, schizophrenia, cognitive communication, artificial limbs, chronic pain, and more.

Research Highlights

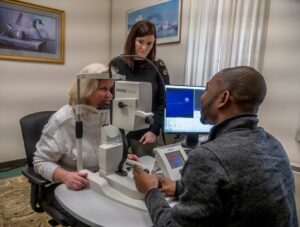

Jessica Alber’s recently received $10.3 million National Institutes of Health grant (Atlas of Retinal Imaging in Alzheimer’s Study – ARIAS) intends to use the eye as a window to the brain to identify the earliest pathological stages of Alzheimer’s disease, prior to the onset of clinical symptoms and loss of daily function. This research provides foundational work towards the validation of Alzheimer’s disease risk screening biomarkers in the human retina. The retina can be imaged using standard optometry and ophthalmology techniques, which allows for accessible and affordable screening for Alzheimer’s disease risk at routine eye exams in older adults, and subsequent referral for more extensive risk evaluation using more invasive techniques at specialty clinics. Alber’s study, titled ARIAS 2, aims to explore the use of cutting-edge plasma biomarkers in conjunction with retinal biomarkers.

Alisa Baron integrates her clinical experience in the schools, private practice, and home health into the classroom environment providing meaningful, real-world examples to her students. Baron’s research is in the area of bilingual language acquisition, language processing, and child language and literacy disorders, focusing on neurotypical Spanish-English bilingual children and children with developmental language disorders as well as heritage Spanish-speaking adults. Baron seeks to understand how English affects Spanish grammar development and vice versa through the use of eye-tracking methodology to better understand how bilinguals process grammatical structures in both languages. Baron, in collaboration with Dr. Mariusz Furmanek and colleagues, was recently awarded a Champlin Foundation grant to facilitate the creation of the Neuro Learning Center and purchase of a near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) system, to allow students to learn about brain imaging techniques within the classroom as well as for use in clinical and research spaces.

Alisa Baron integrates her clinical experience in the schools, private practice, and home health into the classroom environment providing meaningful, real-world examples to her students. Baron’s research is in the area of bilingual language acquisition, language processing, and child language and literacy disorders, focusing on neurotypical Spanish-English bilingual children and children with developmental language disorders as well as heritage Spanish-speaking adults. Baron seeks to understand how English affects Spanish grammar development and vice versa through the use of eye-tracking methodology to better understand how bilinguals process grammatical structures in both languages. Baron, in collaboration with Dr. Mariusz Furmanek and colleagues, was recently awarded a Champlin Foundation grant to facilitate the creation of the Neuro Learning Center and purchase of a near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) system, to allow students to learn about brain imaging techniques within the classroom as well as for use in clinical and research spaces.

Walt Besio has both academic and industrial experience and performs pragmatic directions of research. Besio specializes in research to develop innovative biomedical instrumentation for diagnosis and therapies for enhancing the lives of persons with neurological disease and disability. This work involves unique patented concentric electrodes for neuromodulation and brain computer interfacing (bidirectional). His research encompasses computer modelling, preclinical animal studies, and human evaluations. The brain signal sensing technology he has developed is gaining traction in the fields of: epilepsy, schizophrenia, sleep, pain, and paralysis, among others. The therapeutic technology, transcranial focal stimulation (TFS) has been shown to: increase GABA, decrease glutamate, stop induced seizures from four different acute seizure models, enhance multiple anti-seizure drugs, protect brain from status epilepticus, protect dopaminergic mechanism in a Parkinson’s model, blocks pain, and is safe in healthy and diseased participants. Beyond research, Besio is translating his technologies from the lab to the bedside and beyond to help alleviate pain and suffering from disease and disability.

Walt Besio has both academic and industrial experience and performs pragmatic directions of research. Besio specializes in research to develop innovative biomedical instrumentation for diagnosis and therapies for enhancing the lives of persons with neurological disease and disability. This work involves unique patented concentric electrodes for neuromodulation and brain computer interfacing (bidirectional). His research encompasses computer modelling, preclinical animal studies, and human evaluations. The brain signal sensing technology he has developed is gaining traction in the fields of: epilepsy, schizophrenia, sleep, pain, and paralysis, among others. The therapeutic technology, transcranial focal stimulation (TFS) has been shown to: increase GABA, decrease glutamate, stop induced seizures from four different acute seizure models, enhance multiple anti-seizure drugs, protect brain from status epilepticus, protect dopaminergic mechanism in a Parkinson’s model, blocks pain, and is safe in healthy and diseased participants. Beyond research, Besio is translating his technologies from the lab to the bedside and beyond to help alleviate pain and suffering from disease and disability.

According to Chris Clarkin, her professional mission as a physical therapist, neuroscientist, professor, and researcher is to improve the lives of people living with neurologic injury and neurodegenerative disease. It’s this mission that motivated Clarkin as a clinician to return to school to receive her PhD in neuroscience in 2020 and pursue a career in research and teaching at URI. Clarkin has also worked as a physical therapist, senior therapist, clinical education coordinator, and clinic director in a variety of settings including acute care, acute rehab, and home health care settings with experience across all diagnoses, focusing on neurologic impairments, amputee, and burn and wound care. At URI, Clarkin’s research focuses on neuroscience and neurodegenerative diseases, specifically experience dependent neuroplasticity and the role therapy can take in shaping the rehabilitation of individuals with neurologic and neurodegenerative diseases.

According to Chris Clarkin, her professional mission as a physical therapist, neuroscientist, professor, and researcher is to improve the lives of people living with neurologic injury and neurodegenerative disease. It’s this mission that motivated Clarkin as a clinician to return to school to receive her PhD in neuroscience in 2020 and pursue a career in research and teaching at URI. Clarkin has also worked as a physical therapist, senior therapist, clinical education coordinator, and clinic director in a variety of settings including acute care, acute rehab, and home health care settings with experience across all diagnoses, focusing on neurologic impairments, amputee, and burn and wound care. At URI, Clarkin’s research focuses on neuroscience and neurodegenerative diseases, specifically experience dependent neuroplasticity and the role therapy can take in shaping the rehabilitation of individuals with neurologic and neurodegenerative diseases.

As the Principal Investigator of the Motor Control and Rehabilitation Laboratory (MCR-Lab) at URI, Mariusz Furmanek’s research focuses on Motor Control and its clinical implication. Furmanek’s research focuses on understanding how humans integrate multisensory information (visual, auditory, proprioception) to produce coordinated movements. More specifically, he is studying neural processes involved in upper extremity coordination during reach-to-grasp actions and postural control, which also relates to the validity and reliability of functional measures of human performance in both physical and virtual environments. Furmanek, in collaboration with Dr. Alisa Baron and multidisciplinary team, was recently awarded a Champlin Foundation grant to facilitate the creation of a Neuro Learning Center, to allow students to learn about brain imaging techniques and their clinical and research applications. Additionally, Furmanek collaborates with engineering professors Dr. R. Abiri and Dr. Y. Shahriari on an NSF-funded project. This initiative aims to create an assistive planar robot equipped with a closed-loop feedback system, monitoring user muscle and brain activity. The goal is to enable adaptive execution of reach and grasp actions.

As the Principal Investigator of the Motor Control and Rehabilitation Laboratory (MCR-Lab) at URI, Mariusz Furmanek’s research focuses on Motor Control and its clinical implication. Furmanek’s research focuses on understanding how humans integrate multisensory information (visual, auditory, proprioception) to produce coordinated movements. More specifically, he is studying neural processes involved in upper extremity coordination during reach-to-grasp actions and postural control, which also relates to the validity and reliability of functional measures of human performance in both physical and virtual environments. Furmanek, in collaboration with Dr. Alisa Baron and multidisciplinary team, was recently awarded a Champlin Foundation grant to facilitate the creation of a Neuro Learning Center, to allow students to learn about brain imaging techniques and their clinical and research applications. Additionally, Furmanek collaborates with engineering professors Dr. R. Abiri and Dr. Y. Shahriari on an NSF-funded project. This initiative aims to create an assistive planar robot equipped with a closed-loop feedback system, monitoring user muscle and brain activity. The goal is to enable adaptive execution of reach and grasp actions.

Vanessa Harwood’s research is aimed at improving diagnostic and therapeutic services for the pediatric clinical populations, with a specific interest in the neurobiological markers of language and literacy impairments. Dr. Harwood uses methodologies such as EEG/ERPs to investigate electrophysiological measures of speech perception and their relationships with behavioral characteristics of language and reading.

Vanessa Harwood’s research is aimed at improving diagnostic and therapeutic services for the pediatric clinical populations, with a specific interest in the neurobiological markers of language and literacy impairments. Dr. Harwood uses methodologies such as EEG/ERPs to investigate electrophysiological measures of speech perception and their relationships with behavioral characteristics of language and reading.

Backed by a $2.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, Kunal Mankodiya and several researchers from the University of Rhode Island and the UMass Chan Medical School are developing a wearable device, called the MINDER-band, that will be able to detect if people are taking their medication for opioid-use disorder, increasing the likelihood they would remain in treatment and ultimately preventing overdose deaths. The device will use a sensor system that employs machine learning to monitor physiological changes in people with opioid-use disorder to identify buprenorphine use, withdrawal, or relapse. As Director of the Wearable Biosensing Lab at URI, Mankodiya earned the NSF CAREER Award in 2016 for enabling research on “Internet of e-textile wearables for telemedicine” and the TechConnect Defense Innovation Award for his work on “Smart Textile Trouser” in 2018, as well as recognition as “Innovator-of-the-year” by Future Textiles Awards, Frankfurt, Germany in 2017.

Backed by a $2.6 million grant from the National Institutes of Health, Kunal Mankodiya and several researchers from the University of Rhode Island and the UMass Chan Medical School are developing a wearable device, called the MINDER-band, that will be able to detect if people are taking their medication for opioid-use disorder, increasing the likelihood they would remain in treatment and ultimately preventing overdose deaths. The device will use a sensor system that employs machine learning to monitor physiological changes in people with opioid-use disorder to identify buprenorphine use, withdrawal, or relapse. As Director of the Wearable Biosensing Lab at URI, Mankodiya earned the NSF CAREER Award in 2016 for enabling research on “Internet of e-textile wearables for telemedicine” and the TechConnect Defense Innovation Award for his work on “Smart Textile Trouser” in 2018, as well as recognition as “Innovator-of-the-year” by Future Textiles Awards, Frankfurt, Germany in 2017.

Lyn Stein has a broad background in psychology, with specific training and expertise in substance abuse, mental health and implementation science. Much of her work is conducted in underserved settings. Stein assists trainees in the application of neuroscience to substance use etiology/treatment, and how to communicate relevant neuroscience information effectively to community providers. Stein is interested in interventions targeting brain circuits (e.g., reward) that may mediate substance use outcomes. She is also interested in use of models in neuroscience to guide both treatment and selection of measures for clinically meaningful outcomes (e.g., relapse).

Lyn Stein has a broad background in psychology, with specific training and expertise in substance abuse, mental health and implementation science. Much of her work is conducted in underserved settings. Stein assists trainees in the application of neuroscience to substance use etiology/treatment, and how to communicate relevant neuroscience information effectively to community providers. Stein is interested in interventions targeting brain circuits (e.g., reward) that may mediate substance use outcomes. She is also interested in use of models in neuroscience to guide both treatment and selection of measures for clinically meaningful outcomes (e.g., relapse).

Cindy Tsotsoros is committed to research across the lifespan, as her work identifies mechanisms of cognition resulting from health and environmental factors, strongly focusing on aging in the neurological, developmental, and psychophysiological correlates of cognition. Funded by the National Institute of Aging, Tsotsoros is currently working on adverse childhood experiences’ role on brain health in the Rhode Island Latina population and is leading original data collection to understand how adverse events including experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction – impact the brain’s plasticity (e.g., neurotrophins) and neuropsychological performance (e.g., executive function) as we age through the use of various tools and skillsets un the service of psychological research including laboratory stress tasks, biomarker collection and analysis, neuropsychological testing, body composition analyses, and empirically validated questionnaires.

Cindy Tsotsoros is committed to research across the lifespan, as her work identifies mechanisms of cognition resulting from health and environmental factors, strongly focusing on aging in the neurological, developmental, and psychophysiological correlates of cognition. Funded by the National Institute of Aging, Tsotsoros is currently working on adverse childhood experiences’ role on brain health in the Rhode Island Latina population and is leading original data collection to understand how adverse events including experiences of abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction – impact the brain’s plasticity (e.g., neurotrophins) and neuropsychological performance (e.g., executive function) as we age through the use of various tools and skillsets un the service of psychological research including laboratory stress tasks, biomarker collection and analysis, neuropsychological testing, body composition analyses, and empirically validated questionnaires.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic neuro-developmental disorder characterized by impulsivity, restlessness, and attention difficulties. ADHD results in academic and social challenges not just for young children, but also for adults including college students. Weyandt, whose research focuses on clinical neuroscience, is recognized nationally and internationally as leading researcher in the assessment and treatment of ADHD, as well as the neuropsychological underpinnings of the disorder. She has also studied the effectiveness of prescription stimulant medication in the treatment of ADHD and is an expert on the misuse of prescription stimulants such as Adderall among college students without ADHD. She and her students were the first to identify specific psychological variables associated with those that misuse prescription stimulants, and have conducted studies concerning the misuse of stimulants across the United States and in Iceland.

Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a chronic neuro-developmental disorder characterized by impulsivity, restlessness, and attention difficulties. ADHD results in academic and social challenges not just for young children, but also for adults including college students. Weyandt, whose research focuses on clinical neuroscience, is recognized nationally and internationally as leading researcher in the assessment and treatment of ADHD, as well as the neuropsychological underpinnings of the disorder. She has also studied the effectiveness of prescription stimulant medication in the treatment of ADHD and is an expert on the misuse of prescription stimulants such as Adderall among college students without ADHD. She and her students were the first to identify specific psychological variables associated with those that misuse prescription stimulants, and have conducted studies concerning the misuse of stimulants across the United States and in Iceland.

Nasser Zawia has made major discoveries about Alzheimer’s disease that have garnered international attention. His latest research on an anti-inflammatory drug used to treat migraines in Europe has led to it being scheduled for human clinical trials as a treatment for Alzheimer’s. He has further developed new analogs of this drug currently under provisional patent protection. In 2005, Zawia announced in a study funded by the National Institutes of Health that Alzheimer’s disease has its foundations in infancy when babies are exposed to low levels of lead. Nine years of follow-up studies and $2 million in grant funding later, he has proven conclusively that infant exposure to lead results in late-age cognitive decline and pathology linked to Alzheimer’s disease. According to Zawia, one of the keys to stopping Alzheimer’s disease is early detection. “If we can diagnose the illness earlier,” he said, “then we might be able to minimize the disease’s effects.”