By: Mary Lind

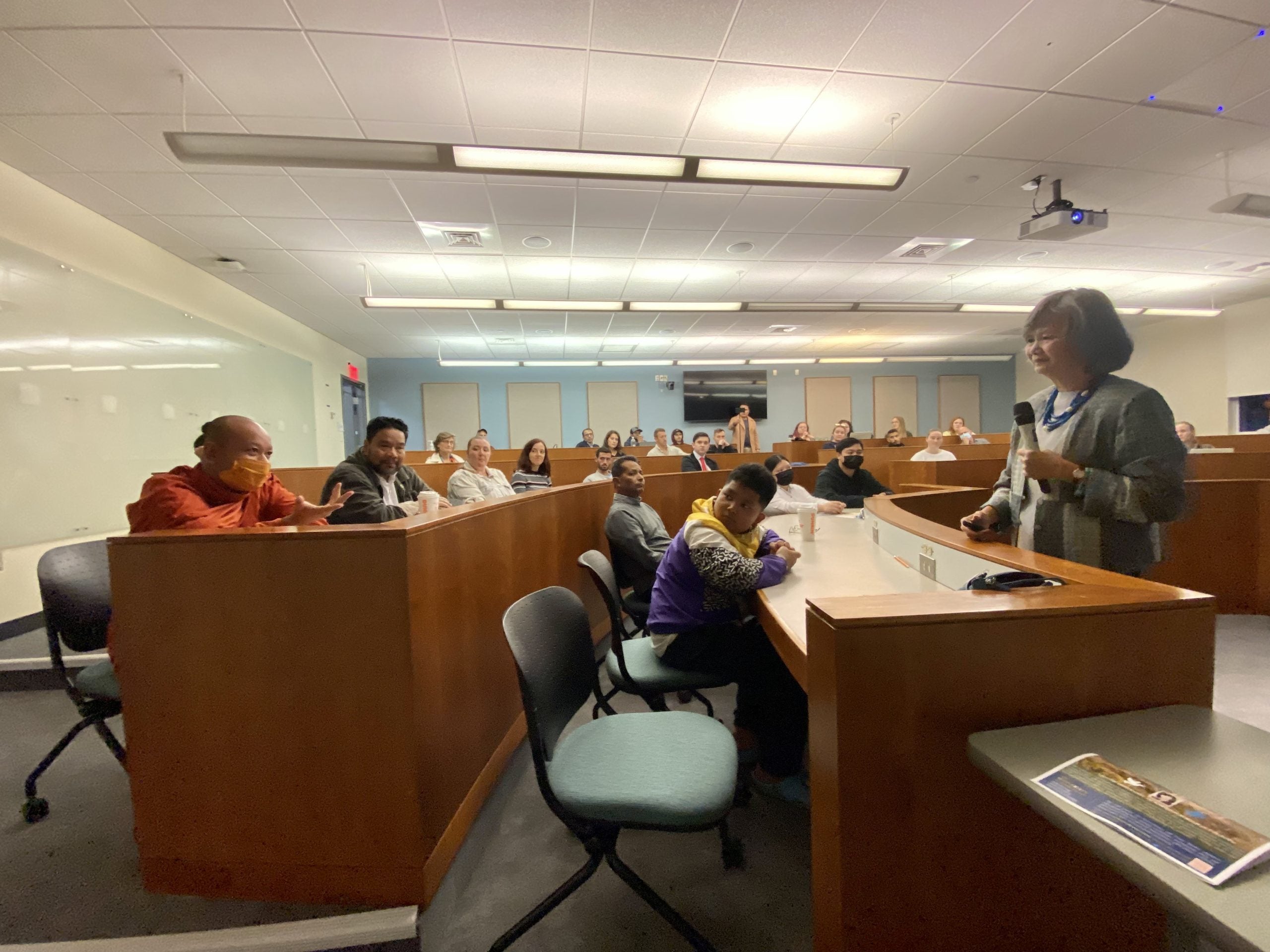

On October 26, 2022, Cambodian human rights activist Mu Sochua gave a guest lecture at URI through the Center for Nonviolence and Peace Studies on nonviolent activism and protecting freedom and human rights in Cambodia.

Sochua, who served both as a Member of Parliament and as Cambodia’s first Minister of Women and Veterans’ Affairs, is currently living in exile and faces a 36-year prison sentence if she returns to Cambodia. The current regime, which Prime Minister Hun Sen (a former military commander) has led since 1985, refuses to allow her to stand trial.

“When you meet a Cambodian, when we see each other, we say ‘choum reap sor,’ which means hello, greetings, how are you,” she said. After a follow-up question of ‘which province are you from,’ the next question is, “where were you between 1975 and 1979?” – the four years of brutal leadership and genocide under dictator Pol Pot and his regime, known as the Khmer Rouge.

Sochua, like many others, lost her parents during that time – “I don’t know where they died, or how they died. But I can assume, like the rest of our parents, starvation, or maybe even worse: torture, because we are half Chinese.”

“During that time, they brought Cambodia back to year zero,” she explained, “meaning no colors whatsoever…the women were separated from the children, the children were separated to serve as spies for the Khmer Rouge, to spy on their parents and to kill their parents.” Refugees walked to the border with Thailand to escape the regime’s brutality. People who wore glasses or had any education would be “automatically killed.”

“So why do we ask right away, ‘where were you between 1975 and 1979?’ Because we want to know so, we can relate to each other. We want to know if you speak the language, if you went through starvation, if you know what hardship is like, if you know what not having an education is like, then we can relate.”

Once the Khmer Rouge fell, Cambodia was occupied by Vietnam until 1991, which “were years of terror as well.” On October 23, 1991, the Paris Peace Agreements (formally titled the Comprehensive Cambodian Peace Agreements) were signed. However, as far as Hun Sen is concerned, the agreement is finished because he does not want to apply it, according to Sochua.

“These moments are very important,” Sochua explained, “the genocide, the occupation of Cambodia by the Vietnamese. That’s why we struggle today, and that’s why we don’t give up.” And Sochua hasn’t given up.

Following her return to Cambodia in 1989, after having been in exile for 18 years, Sochua started an organization for women called Khemara and participated in a peace walk through Cambodia starting at the Thai border to call for peaceful elections.

“That’s when I started to know the word nonviolence,” she said. “The women joined the peace walk. We came from everywhere. People started to come out from villages, remote villages, to walk the peace walk with the Monks, with Maha Ghosananda,” a high-ranking Buddhist monk who led the first peace walk after he returned from exile following the war as well.

“It was the purest, most beautiful moment after the dark with the genocide and the occupation. It was bigger than Cambodia. We had hope everywhere, and we started to love each other again.” Buddhism began to grow in Cambodia again after many monks had been tortured and killed during the Khmer Rouge.

In 1993, in Cambodia’s first election following the Paris Agreement, 99% of the population voted. “They all wanted to vote for change. No return to the genocide. No more communism. No more weak leadership. No more one-party state.” Cambodia had its first constitution in 1993, and Sochua described it as “a very liberal constitution.”

“The whole chapter 3 is totally about human rights. All of the Universal Declaration of Human rights are in it. There are at least five articles just for women’s rights.” Rebuilding Cambodia was a gargantuan task – “how do you rebuild a nation that is totally, totally demolished?” she asked, “you can put a number, but you cannot rebuild a soul once it has been destroyed.”

Today, though, Cambodia is a one-party state. And Sochua is labeled by some as a traitor. “If there were truly human rights and observation of human rights and fundamental freedom in Cambodia, I wouldn’t be here,” she said. “We would not be here. We would be in Cambodia rebuilding Cambodia. But they don’t let us be a part of rebuilding Cambodia because we want to rebuild Cambodia based on human rights and fundamental freedom.” She said that Cambodia doesn’t exist now, but it used to.

“It existed when we were there. We won, we would’ve won the elections, but they did not want us. They dissolved our party…but we were too strong, which challenged the dictatorship. That’s why we are here in America. But we are not giving up.”

In 2013, her party, the opposition party, won the election, but the National Election Committee was not independent. “It was fraudulent,” she said, “and we contested the election result.”

People marched in the street, joined by the monks. What began as a walk became “a nonviolent movement to change and to disrupt and to take Cambodia back to where people want Cambodia to be, which is a free, truly free, people.”

Sochua was the organizer of the peaceful movement at a place called Freedom Park, where people gathered for months to demonstrate. Monks and students built networks to protect Cambodian forests and continue the protest. Workers eventually joined the movement as well. They all wanted change, and they all wanted democracy, Sochua said.

However, the regime eventually brought in barbed wire, tanks from China, and weapons. Keeping in mind words from Maha Ghosananda, Sochua and the other movement leaders retreated.

“We said we could not see any more blood on the street. We retreated, and the people were very angry.” Sochua emphasized that they did not want to take Cambodia back to a time of violence.

“We retreated, but I was a rebel,” she said. Instead of going back home, she returned to Freedom Park. “Freedom park was not free anymore. We spoke to the soldiers; we reasoned with them. We gave them lotus flowers. We gave them water. We chanted with them, and they said we stand with you, but we can’t.” Sochua was locked in jail for seven days.

Today in Cambodia, casino workers (who were also at Freedom Park) have been striking for over a year, employing nonviolent techniques such as sit-ins and meditations. The Cambodian diaspora from all over the world “are with us because they have families back in Cambodia. Because they know what freedom is and what democracy is like. They are not willing, and they can not accept for Hum Sen to remain in power. He wants to be in power until the day he dies.”

Even abroad, Hun Sen’s regime is still following Cambodians. “There are pagodas, three pagodas in Rhode Island,” she said, “and the regime is also in Rhode Island. They are also accepted by the United States. They are citizens of America now, but they’re with the regime. So they are agents of the regime in America, in Australia. Their objective is to conquer and divide the community.”

There are many pagodas in the US, but one pagoda, in particular, Sochua said, is free from the regime. “This pagoda is not just a pagoda; it’s a center for democracy. You can go to talk politics, but no one will be there to report what you say or take pictures to Hun Sen and complain. We are safe.”

Sochua travels the world to pressure leaders to stand up for democracy, freedom, and human rights in Cambodia and to uphold their end of the Paris Agreement. In September, when Hun Sen was delivering a speech at the UN Headquarters in New York City, Sochua and many others from across the country and the world protested outside. “We said, the dictator is at the UN! What is the UN for?”

Even though Sochua and the Cambodian diaspora are working across the globe to fight for Cambodia’s freedom, they have not forgotten the political prisoners still suffering in Cambodia. Sochua showed photos of political prisoners and spoke of the organization she started, Courage Fund Cambodia, to further their cause and to raise awareness and funds for those impacted by the repressive practices of the Hun Sen regime.

“Our mission is to free all political prisoners in Cambodia. And for us to return home, so that we can hold elections in July 2023. It is very difficult, but we have never to give up hope.”

Sochua’s lecture was well received. The images she presented were powerful. Many students, faculty, staff, and community members appreciated her nonviolent struggle to rebuild beautiful Cambodia and educate them about the Cambodian issue.