Exposure

Where do PFAS come from?

There are three primary sources of PFAS contamination: (1) aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) use at civilian and military airports, industrial sites, and firefighting training centers to suppress fires; (2) industrial PFAS production by eight major industries in the U.S.; and (3) manufacturing sites of PFAS-containing products, such as carpets or car parts.

There are more than 600 PFAS contaminated sites around the country, many of which will require remediation or treatment, and some are already identified as official Superfund sites. At least 14 Superfund sites on the U.S. EPA National Priorities List are co-contaminated by PFAS. In addition, the release of PFAS to the environment and their use in consumer goods has resulted in contamination that has become global in extent and caused substantial background exposure to PFAS that affect all Americans.

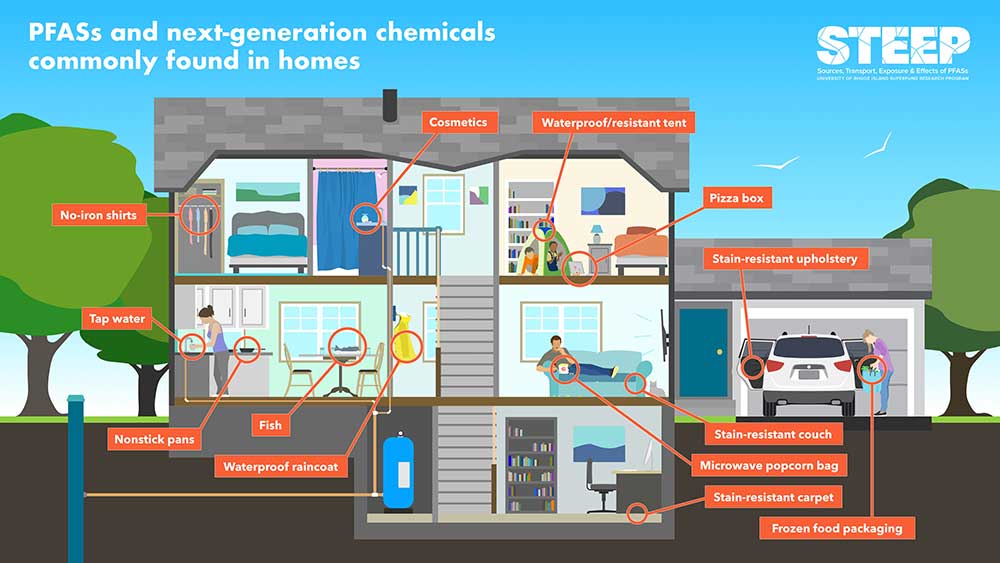

Where can you find PFAS?

Most prominently, in your own home. If you own water resistant clothing, have stain repellent carpets, or eat food from grease-proof packaging, chances are you are exposed to a range of PFAS. The good news is that you can choose not to use these products. There is widespread use of PFAS in consumer products, and the Top 9 are:

- Takeout containers such as pizza boxes and sandwich wrappers

- Non-stick pots, pans, and utensils

- Popcorn bags

- Outdoor clothing

- Camping tents

- Stain-repellant or water-repellant clothing

- Stain treatments for clothing and furniture

- Carpeting and carpet treatments

- Certain cosmetics

To learn more about identified consumer goods, visit:

Green Science Policy Institute

Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry

Environmental Working Group

PFAS are also found in drinking water, air, and dust. Of these, drinking water is a major concern. PFAS that are released from manufacturing and industrial sites can make their way to local groundwater supplies. Once in the groundwater, they not only enter the food web, with fish as one example, but also find their way into drinking water through both municipal supplies and private wells.

Municipal wastewater facilities that treat PFAS-contaminated water produce PFAS-contaminated sludge. This sludge is treated according to EPA standards to reduce pathogens and heavy metals, and it is then reclassified as biosolids that is safe for farmers to spread on fields to fertilize crops. The treatment, however, does not remove PFAS from the sludge, and the resultant biosolids can introduce PFAS to water systems that are far from a PFAS source.

PFAS can seep from biosolids to local water supplies that are used to provide water to farm animals including dairy cows. In Vermont, local farmers have had to dispose of milk from their dairy cows after testing revealed high levels of PFAS. STEEP researchers are working in Vermont to investigate how PFAS in biosolids spread through water systems.