Traditional PFAS monitoring methods often only test for 25 or fewer compounds, typically focusing on terminal compounds—those that do not degrade under normal environmental conditions, such as PFOA and PFOS. Precursor compounds—those that can be transformed through biological or environmental processes into terminal forms—often make up the majority of PFAS chemicals in a sample including fire-fighting foams, but are often overlooked by traditional testing methods. However, Dr. Elsie Sunderland’s lab, STEEP Project 1 out of Harvard University’s John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Science, has developed a new combination of testing methods to overcome this barrier and account for all PFAS in statistical source attribution modeling.

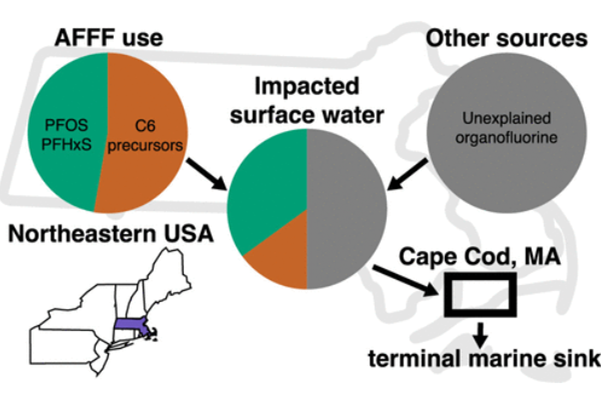

“We developed a method to fully capture and characterize all PFAS from fire-fighting foams, which are a major source of PFAS to downstream drinking water and ecosystems. However, we also found large amounts of unidentified PFAS that couldn’t have originated from these foams,” said Bridger Ruyle, STEEP trainee and first author of the study. The method combines measurements of terminal compounds as well as oxidizable precursor and extractable organofluorine. Measured concentrations are used in statistical models that predict the perfluorinated chain length and origin of precursors as well as reveal the predominant PFAS signatures in six adjacent watersheds on Cape Cod with and without upstream fire-fighting foam use. The researchers found that while fire-fighting foams contributed to much higher concentrations of terminal PFAS and precursors in downstream watersheds, an additional 50% of PFAS compounds was identified for the first time from currently unknown sources. The team is preforming follow-up studies to try to identify these PFAS and their origins.

The study was published earlier this year in Environmental Science & Technology, and was highlighted in the Harvard Gazette, Cape Cod Times and Boston Globe.