Are PFAS being phased out?

As a result of health concerns, the 3M Company, a main producer of PFAS, voluntarily phased out PFOS in 2002, and the U.S. has introduced additional voluntary programs to curb the production and use of PFOS and PFOA; however, production continues elsewhere, mainly in Asia, and the U.S. continues to produce other fluorinated compounds without adequate regulatory oversight.

Even as we phase out earlier PFAS compounds, they remain in the global environment. But new fluorinated compounds have been and continue to be developed to replace the phased out ones. As the Environmental Working Group notes, U.S. chemical manufacturers have replaced the phased out PFAS chemicals with reformulated “short-chain” PFAS. Manufacturers claim the new chemicals are less likely to build up in our bodies, but these compounds were not adequately tested for safety before going on the market, and the limited research available suggests they may have similar health hazards to the earlier longer chain PFAS. More than 5,000 PFAS have been or now are used worldwide.

It is critical that Americans need to join with other countries in demanding both a standard of lower exposure levels to any chemicals identified as harmful and more rigorous testing of new chemicals prior to their widespread use. Impacted communities are already demanding information and action related to PFAS. If we don’t take action, then we will continue to play whack-a-mole since as soon as we address one chemical, research validates suspected problems with several more.

Madrid Statement Calls for Action on PFAS

In 2015, over 250 scientists from nearly 40 countries around the world signed the Madrid Statement, highlighting that persistent PFAS chemicals have a range of detrimental effects and questioning the use of new alternatives that are just variations of previous PFAS. In an accompanying editorial in the journal Environmental Health Perspectives, STEEP co-director Philippe Grandjean called for cooperation across the globe between scientists, governments, manufacturers, and the public to limit PFAS production and shift to safer alternatives.

What is being done?

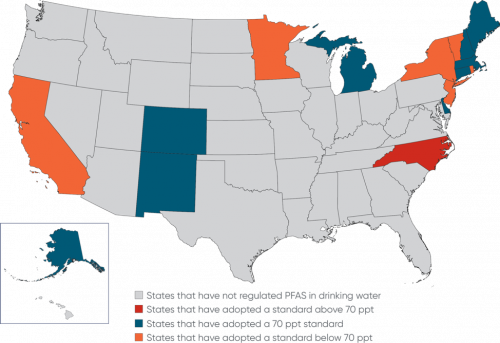

At the federal level, U.S. EPA has not yet established regulations for PFOS or PFOA (the two most common classes of PFAS), and so far only provisional health advisories of 70 parts per trillion (ppt) exist for drinking water. Recent focus on PFAS through national attention on areas like Hoosick Falls, NY, increased scientific research and publication of findings has resulted in U.S. EPA talking publicly about PFAS, though more concrete steps have not yet been taken by the agency. It published a PFAS Action Plan in February 2019 with an update in February 2020. Currently actions have been focused on proposing to regulate PFOS and PFOA and supporting state and tribal efforts to regulate the chemicals.

Several states have not waited for U.S. EPA to act, and have adopted the provisional health advisory level of 70 ppt, including Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Michigan, Colorado, Delaware, Colorado, New Mexico, and Alaska. Unfortunately, researchers advise that this health advisory level is nowhere near sufficient to protect human health, and a standard of 7 ppt is highly advisible; however, STEEP scientists highlight that an even lower level of 1 ppt is essential to completely protect human health while also acknowledging that this may not currently be possible.

The concept of essential use for determining when uses of PFAS can be phased out (2019) Ian T. Cousins, Gretta Goldenman, Dorte Herzke, Rainer Lohmann, Mark Miller, Carla A. Ng, Sharyle Patton, Martin Scheringer, Xenia Trier, Lena Vierke, Zhanyun Wang, and Jamie C. DeWitt

One group of scientists including STEEP’s PI, Dr. Rainer Lohmann, has published papers proposing the phasing out of PFAS-based products based on “essentiality” of use, e.g., food container coating could be eliminated while AFFF would continue until a PFAS-free product is developed. This approach recognizes the value and efficacy of these chemicals while balancing that with the long-term perils of human exposure.

Fortunately, individual states are starting to grasp the seriousness of this emerging contaminant and some are taking action to protect their residents. As of 2019, six states have proposed or enacted regulations below the 70 ppt provisional health advisory level. The New York Drinking Water Council has proposed the lowest limit for PFOS and PFOA to date of 10 ppt, but that recommendation has yet to be adopted. California currently has the lowest limit approved for regulation of 13 ppt for PFOS and 14 ppt for PFOA.

David and Goliath

People or groups that have been exposed to PFAS are taking their cases to court to seek action. A major case was Minnesota v. 3M. 3M, one of America’s leading chemical corporations, used PFAS chemicals starting in the late 1940s (e.g., Scotchgard and firefighting foams), and disposed of them in Minnesota dumpsites until the 1970s. After the 70s, 3M continued to use PFAS in their manufactured products but disposed of them through incineration, but this process is not widely effective due to uneven management of pollution from smokestakes and subsequent airborne distribution of PFAS. Eventually, 3M completely phased out its use of PFAS in 2002, following an agreement with the EPA in response to escalating concern about their effects.

The damage was already done. The PFAS chemicals disposed of at landfill sites in Minnesota leached into groundwater and contaminated residential wells. In 2004, traces of the chemicals were found in the drinking water of about 67,000 people. In 2007, 3M signed an agreement with the State of Minnesota to finance $40 million for cleanup of landfills and to provide drinking water to contaminated communities. In 2010, Minnesota’s Attorney General sued 3M for an additional $5 billion, stating that once 3M knew the effects of PFAS the corporation continued to dispose of them improperly. 3M argued that it fulfilled its legal obligations through its previous 2007 agreement with the state, and that its activities regarding disposal of the chemicals were legal at the time. The parties reached a settlement agreement before the trial was scheduled to begin. 3M agreed to pay $850 million toward cleaning up the drinking water and environmental improvements. It also agreed to continue to pay the previously capped $40 million under the 2007 agreement. It is worth noting that 3M did not admit to any liability and all of the damages 3M agreed to pay are related to environmental damage and not human health. 3M documents that were made available to Minnesota are available on the state Attorney General’s website; however, the settlement allowed the company to avoid making many other internal documents public.

Other states are also seeking action through the courts, including:

- Michigan sued Wolverine World Wide for disposing of PFAS-contaminated tannery waste that caused well water contamination. The parties agreed that Wolverine World Wide would pay $69.5 million—of which 3M is responsible for $55 million—to extend the water system to about 1,000 homes in a PFAS contamination zone.

- Vermont and Saint-Gobain, manufacturer of building and high-performance materials, reached a settlement of $20 million to improve water lines for half of impacted properties, and are currently negotiating a settlement for the other half. In addition, individuals are attempting to move forward a class action suit related to health impacts.

- In October 2020, South Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and Chemours chemical company entered into an agreement that will stop Chemours from discharging 99% of its GenX and other PFAS pollution into the Cape Fear River.

Individuals are also working through the court system to seek compensation for personal harm resulting from PFAS contamination:

- In 2019, hundreds of individual cases alleging harm from aqueous film forming foams (AFFFs) were combined into a single complex litigation case, which is being overseen by a federal judge in South Carolina.

- In 2020, two class action lawsuits, representing thousands of individuals was filed against Chemours in North Carolina related to PFAS contamination from its Fayetteville Works plant.

These are just a few examples of how states and individuals are working through the judicial system to reduce PFAS pollution and gain compensation for their exposure to the chemicals.