One of the pressing issues in PFAS research and regulations is the recognition that few of the thousands of individual PFAS compounds have been studied in detail. STEEP graduate Anna Robuck, STEEP researcher Rainer Lohmann, and a team of coauthors recently published a study in Environmental Science & Technology Letters. In it, the researchers characterize the behavior of 36 legacy and emerging PFAS compounds in seabird tissues.

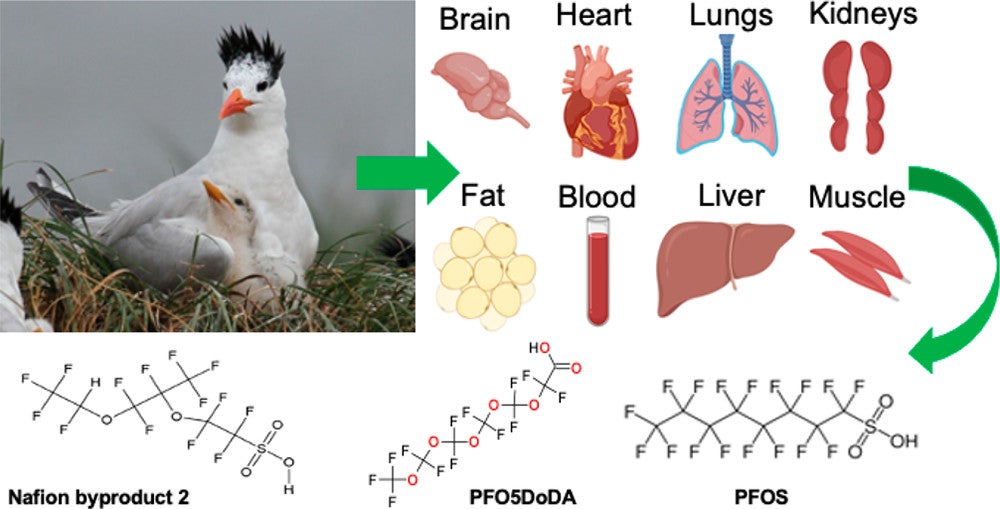

The group collected tissue samples from juvenile seabirds, including herring gulls, royal terns, and brown pelicans, found around Massachusetts Bay, Narragansett Bay, and the Cape Fear River Estuary. Because PFAS compounds may distribute themselves and behave differently in different parts of the body, the researchers wanted to assess PFAS exposure by looking at a wide range of tissue types. They analyzed samples from 8 different types of tissue: brain, heart, lungs, kidneys, fat, blood, liver, and muscle.

The researchers looked at a newer group of PFAS in particular, per- and polyfluoroalkyl ether acids (PFEA). They found that novel PFEA in the juvenile seabirds tend to partition to the blood more than the liver. This study is also the first to document PFEA in brain tissue. This finding is an important development because the brain is often well protected from contaminants, and yet these PFEA compounds were able to cross the blood-brain barrier to enter brain tissue.

PFEA have been used as replacements for legacy PFAS compounds that have been phased out. Because PFEA are newer, less information exists on their effects on humans and wildlife. While the health consequences remain unknown, this research provides a detailed picture of how novel PFEA behave in the bodies of juvenile seabirds. These findings could help guide future work on other species, including humans.

maximus maximus), the 8 types of tissue that were sampled, and three of the PFAS compounds

analyzed in the study. PFOS is a legacy PFAS, and PFO5DoDA and Nafion byproduct-2 are

novel PFAS.