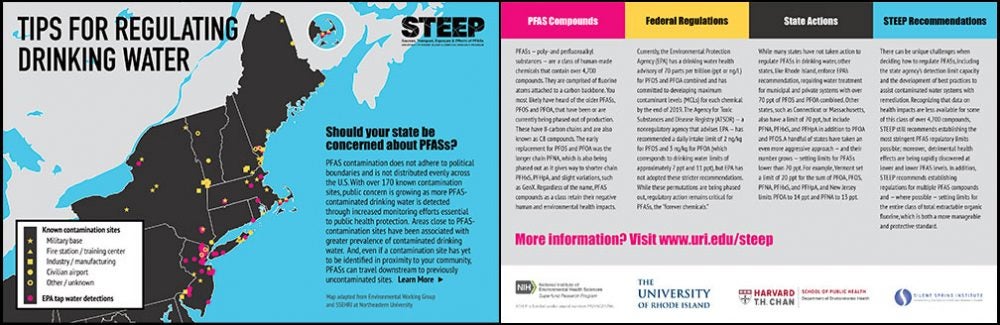

Should your state be concerned about PFAS?

PFAS contamination does not adhere to political boundaries and is not distributed evenly across the U.S. With over 170 known contamination sites, public concern is growing as more PFAS-contaminated drinking water is detected through increased monitoring efforts essential to public health protection. Areas close to PFAS contamination sites have been associated with greater prevalence of contaminated drinking water. And, even if a contamination site has yet to be identified in proximity to your community, PFAS can travel downstream to previously uncontaminated sites.

PFAS Compounds

PFAS—poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances—are a class of human-made chemicals that contain over 4,700 compounds. They are comprised of fluorine atoms attached to a carbon backbone. You most likely have heard of the older PFAS, PFOS and PFOA, that have been or are currently being phased out of production. These have 8-carbon chains and are also known as C8 compounds. The early replacement for PFOS and PFOA was the longer chain PFNA, which is also being phased out as it gives way to shorter-chain PFHxS, PFHpA, and slight variations, such as GenX. Regardless of the name, PFAS compounds as a class retain their negative human and environmental health impacts.

Federal Regulations

Currently, the EPA has a drinking water health advisory of 70 parts per trillion (ppt or ng/L) for PFOS and PFOA combined and has committed to propose a regulatory determination for PFOA and PFOS by the end of 2019. If it determines that PFOA and PFOS should be regulated, then actual MCL development will begin after that and could take as long as 18 months to two years. The Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) —a nonregulatory agency that advises EPA—has recommended a daily intake limit of 2 ng/kg for PFOS and 3 ng/kg for PFOA (which corresponds to drinking water limits of approximately 7 ppt and 11 ppt), but EPA has not adopted these stricter recommendations. While these permutations are being phased out, regulatory action remains critical for PFAS, the “forever chemicals.”

State Actions

While many states have not taken action to regulate PFAS in drinking water, other states, like Rhode Island, enforce EPA’s recommendation, requiring water treatment for systems with over 70 ppt of PFOS and PFOA combined. Other states, such as Connecticut or Massachusetts, also have a limit of 70 ppt, but include PFNA, PFHxS, and PFHpA in addition to PFOA and PFOS. A handful of states have taken an even more aggressive approach—and their number grows—setting limits for PFAS lower than 70 ppt. For example, Vermont set a limit of 20 ppt for the sum of PFOA, PFOS, PFNA, PFHxS, and PFHpA, and New Jersey limits PFOA to 14 ppt and PFNA to 13 ppt.

STEEP Recommendations

There can be unique challenges when deciding how to regulate PFAS, including the state agency’s detection limit capacity and the development of best practices to assist contaminated water systems with remediation. Recognizing that data on health impacts are less available for some of this class of over 4,700 compounds, STEEP still recommends establishing the most stringent PFAS regulatory limits possible; moreover, detrimental health effects are being rapidly discovered at lower and lower PFAS levels. In addition, STEEP recommends establishing regulations for multiple PFAS compounds and—where possible—setting limits for the entire class of total extractable organic fluorine, which is both a more manageable and protective standard.

Learn about state and federal actions as well as STEEP recommendations.