Artificial intelligence (AI) has been experiencing a massive boom in its incorporation into personal, professional, and academic spaces. It is increasingly being used in the United Nation’s global negotiations for summarizing information, providing policy suggestions, and answering complex questions related to global policy. While there are numerous opportunities for its application, it can also have unintended negative consequences due to inherent biases and unequal distribution of resources among nation-states.

University of Rhode Island’s Professor of Marine Affairs Yoshitaka Ota has been working with colleagues to closely examine pitfalls in AI within marine policy in particular. He and his team had their research recently published in the international peer-reviewed journal npj Ocean Sustainability. The article presents a case study of an AI chatbot that the team developed – the Experimental BBNJ Question-Answering Bot – to explore the opportunities, limitations, and risks that artificial intelligence language learning models (LLMs) present in the global ocean policy space.

Artificial Intelligence and Ocean Policy

While artificial intelligence is increasingly being used in ocean policymaking, disparities exist that put developing nations at a disadvantage. While there is potential for LLMs to aid researchers and diplomats in UN negotiations, there also exists a concern about biases that may exist within AI and its means of obtaining or disseminating information. In the article, the authors mention a growing amount of research exposing inherent biases in many AI models which arise from the training and design fed to them. Such models are prone to reproducing harmful stereotypes, leading to discrimination in job hiring systems, advertisements, and even criminal sentencing (Ziegler et al., 2025).

The authors also point out the ways in which misplaced trust in LLMs can have negative impacts and further influence bias in both the AI systems and the policymakers who become dependent on them. Over-reliance on AI technology, the authors note, may lead to a form of “automation bias” in which people defer to AI systems over more reputable sources. Confirmation bias is another concern, in which individuals may trust the responses of an AI system instead of fact-checking. This can also look like individuals favoring LLM responses that align with their own beliefs rather than incorporating information and perspectives from those that differ from their own. This over-reliance and misplaced trust can have disastrous consequences by reproducing and repeating unjust, biased, or discriminatory language. These concerns are what drove the team to develop the BBNJ Question-Answering Bot in order to examine how LLMs like ChatGPT could influence ocean policy negotiations.

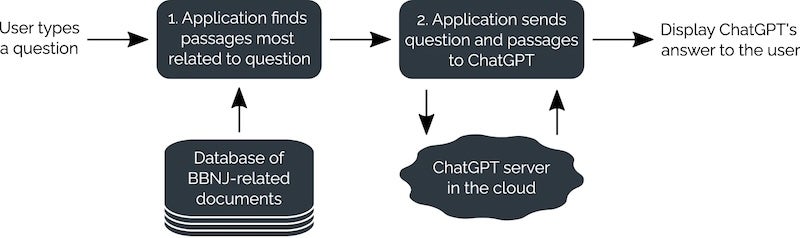

The team’s experimental chatbot was named for the recently adopted UN agreement on marine conservation and “biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction,” or the BBNJ Agreement. This agreement was selected for testing by the bot because of its lengthy and complicated period of negotiations which reflected patterns of inequity between developed and developing nation-states. Thus, the experimental chatbot gave researchers an opportunity to test what kinds of responses the bot would provide when prompted and the ways that implicit biases could be introduced in its responses. An example of this is when the BBNJ Question-Answering Bot was asked about how the BBNJ Agreement could impact human rights abuses for countries like Thailand and the U.S. The article includes a figure with both the questions researchers asked and the chatbot’s responses, illustrating how certain biases that may favor or disfavor a certain country, belief, or way of thinking can influence not only the training behind chatbot models, but also the responses it provides.

Four Pillars of Ocean Governance

Ocean governance refers to how the world’s oceans and its resources are managed. “One side of it is how to govern the ocean: the structure of the governments, laws, and systems that govern,” Ota says. “Part of this side is understanding the system: how the law is deployed, what resources are given, etc. The other side is the accountability, legitimacy, transparency, and responsibility of how we are governing oceans. This side centers on assessing if the way we’re doing this is legitimate and accountable, whether people are actually taking responsibility.”

Bridging technology and equity in global ocean governance is the central focus of the team’s project. Matt Ziegler, Ocean Nexus Innovation Fellow, shared how AI is being incorporated in ocean governance talks and the risks it can pose to less-resourced nations. “There’s a lot more uses of AI being proposed in ocean governance, such as modeling that comes up for estimating things like fish populations in future years, and proposing designs for protected areas,” he says. “It’s essentially being used by countries bringing in a lot of resources, so we are hoping that this paper will give the less-resourced countries a way to question that, and show the real risks of introducing the same kinds of human biases and putting those lower-resourced countries at a disadvantage.”

AI and Ocean Governance: How the Project Came to Be

Ota is driven by collaboration, accountability, and responsibility in global ocean governance, which spurred the development of Ocean Nexus, an ocean research institute that brings scholars together from across the globe. He was interested in investigating how technology could be used for ocean governance in terms of increasing transparency and accountability and began collaborating with Ziegler, who was working on projects related to development of technology such as artificial intelligence models. In the paper, the authors write: “LLMs are already having an impact on marine policymaking processes, despite their risks being poorly understood. A number of this paper’s authors have already observed State representatives and delegates using ChatGPT at the UN for purposes including the drafting of interventions, statements, submissions, and biographies; asking it questions to conduct background research; and even generating whole presentations. Some countries have already developed policies for ChatGPT use for their governmental officials” (Ziegler et al., 2025).

“In UN negotiations, there is a huge imbalance between countries with access to researching information and resources, and those which don’t,” Ota adds. “We were asked by colleagues working with those within these negotiations to assess whether ChatGPT is safe to use and how useful it could really be. That’s how this project came to be.”

Looking Toward a More Equitable Future

“We are still hopeful that LLMs could yield some positive results for developing States and other marginalized actors, despite the equity concerns that we have outlined,” note Ota and colleagues in their paper. They outline areas where AI can prove useful for improving equity in ocean governance, such as helping to draft legislation, understand policies, and aid in international consults (Ziegler et al., 2025). The research team remains optimistic, though cautious, about the future of AI technology’s use in global ocean policy. They hope that their work helps open up further discussion at the table for how to leverage technology in equitable, accountable, and responsible ways among nations at the international negotiation tables.

Ota shared how the team intends to use the study’s findings to create a training program for policymaking. He said, “We are hoping to create a training program for the people in those negotiations. It’s a short training to basically teach people that you can still use ChatGPT, but there are things you need to be careful of. We ran a workshop with the Ocean Voices group called ChatGPT for Policymaking Practitioners.” Another training, Designing Equitable Ocean Technology, is also available online. Through such trainings, Ota and Ziegler aim to work with policymakers to understand the risks of AI technology while developing equitable ways to incorporate such technology into marine policy. Ota adds, “We are actively engaging with those who are in ocean governance to understand this risk. This paper is like the evidence for us to say, ‘We have a major publication, so we know that this technology is biased.’”

You can read the full article here.

Written by Yvonne Wingard, CELS Communications Fellow