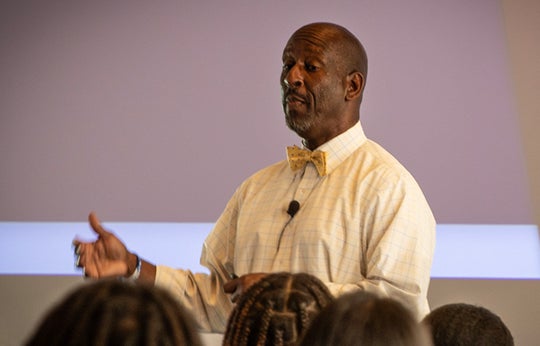

October’s Distinguished Speaker event featured Dr. Dorian L. McCoy, director of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville’s College of Education, Health, and Human Sciences, who shared his expertise on navigating turbulent socio-political landscapes and creating partnerships, with about 70 students and faculty at URI’s Carothers Library on Oct. 2.

“Dialogue is always best,” he said as he began his presentation, “but some people are not comfortable taking about these topics.”

In his lectures, McCoy engages across differences in the socio-political climate to avoid a “scorched earth, burn down the house” approach, and encourages courageous leadership that identifies common ground and works across differences.

“We need to understand that much of this is rhetoric for political gain and not about educating/not educating our students,” he said.

Being a successful educator and lecturer didn’t come without its obstacles. He had to build confidence in his own voice to better share and learn not to judge.

“Once I learned that mistakes are part of the process and that I had a community of support to encourage and assist with educating me, I relaxed and became better,” he said.

Q and A with Dr. Dorian McCoy

Q.What are the best ways to open a dialogue?

McCoy: Meet people where they are. Do not engage in a judgmental way. Let them know you are seeking to understand, even though you may disagree. Engage in a civil discourse. Do not argue, yell, scream. Most people want to be heard. Do not “embarrass” them. Be inquisitive and curious. For example, “I hear you. I am not sure I agree. Have you considered ‘X, Y, Z.’ Do you understand why someone may have a differing opinion based on their experiences? Tell me more about why you feel that way?” I try to start from a place of common ground and build on that.

Q.Your talk at URI was about “Navigating Turbulent Socio-Political Landscapes and Creating Partnerships.” How does one inform the other?

McCoy: Partnerships are grounded in common interests. I am not sure U.S. society is in a place with numerous common interests. Politically, we are extremely divided. Those committed to DEI, social justice, etc. are struggling to find a common ground with those opposed to equity and inclusion. At this point, I think we need to seek understanding and hope this political movement (anti-DEI, anti-CRT) subsides and U.S. citizens are more logical. I hate to use a cliché, but this too shall pass. That is a fact. The question is, “How much harm will be done before it passes?” Given the current socio-political context, I believe they inform each other.

Q. What are some of the critical theories that you see as not being properly addressed and possibly harming people of this country in their inaccuracy and/or sanitizing?

McCoy: I don’t see critical theories harming people. Theories are frameworks for supporting scholarly efforts (e.g., research, etc.). Most theories have “areas of improvement.” However, if I am a proponent of White supremacy as a theory (not a critical theory and not sure it is theory, but definitely an ideology), I find that harmful. There are many (non-academics and perhaps a few academics) who support White supremacy as a guiding ideology. Unfortunately, racism has been reduced to individual and group levels and many refuse to see how it manifests at the organizational/institutional level.

Q. As an expert, why is critical race theory such a fierce debate among educators in how students are being taught?

McCoy: The debate is not necessarily among educators. It is with elected officials legislating what can be taught and how it should be taught. I ask, “Who are they protecting?” History will always be taught, learned, and shared. You cannot engage in erasure, if this was so, we would not know the horrors of the 18th and 19th centuries (eradication of Native/Indigenous People and the enslavement of Africans). Enslaved people could not read, but their history was shared via oral histories/stories.

Q. You spoke of “the narrative and who is controlling it. “What does that mean? What is the biggest obstacle for under-represented people to change the direction of the narrative?

McCoy: There is an African proverb: “Until the lion tells the story, the hunter will always be the hero.” There cannot be this singular narrative framed in positivity. That is not reality. Every nation has a sordid history. We must grapple with that, and there needs to be reconciliation. Underrepresented people need to tell and share their stories.

Q. How can educators better frame socio-political content to navigate the narrative in this country, given the curricular restrictions?

McCoy: Unfortunately, we need to educate others about the importance of our work and how the work that is being done is not indoctrination. History is ugly. It’s messy. We must grapple with all of its complexities.