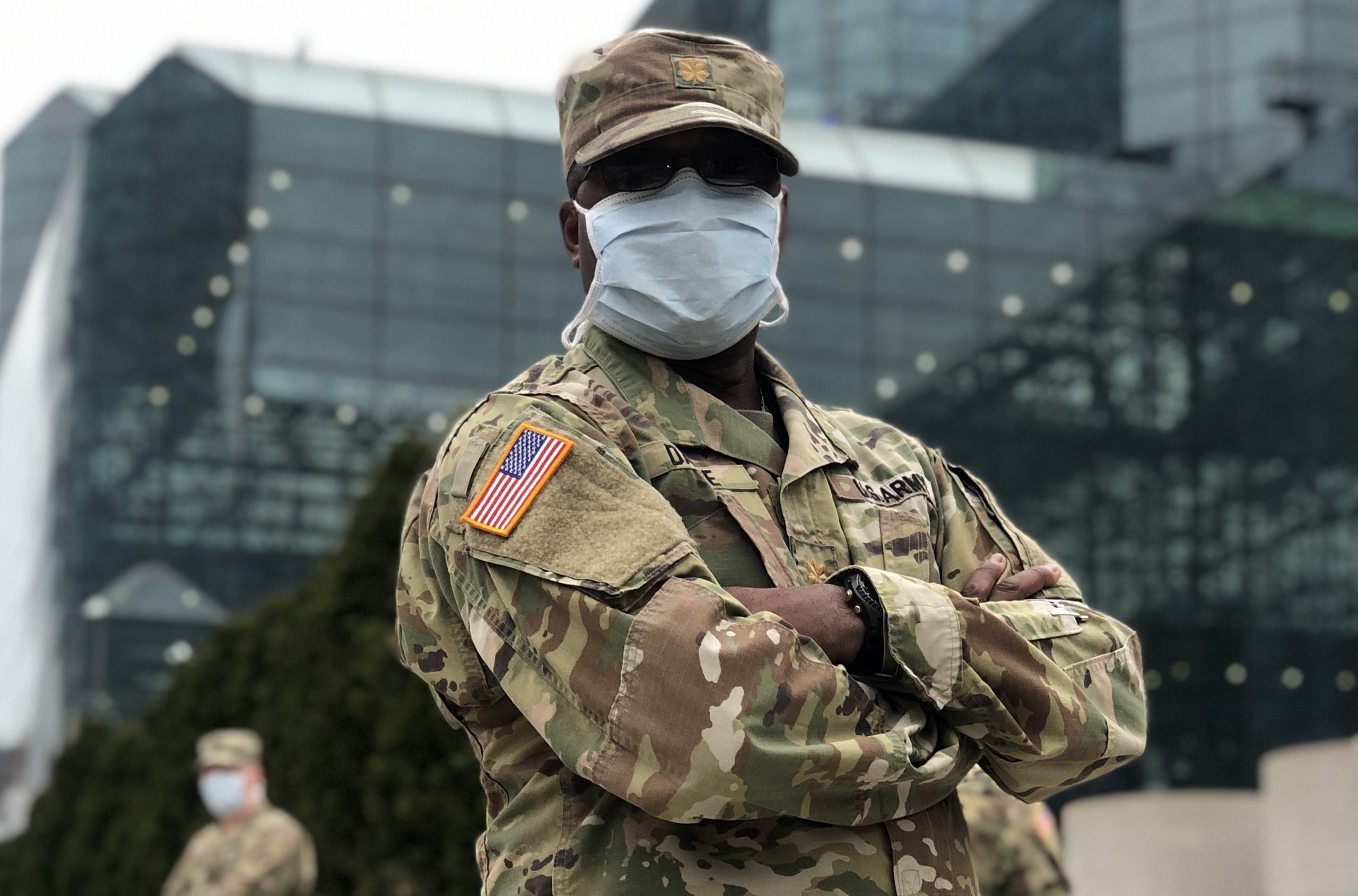

Wylie Dassie cared for COVID patients in New York City during the height of the pandemic

Clinical Assistant Professor Wylie Dassie left the classroom for the hot zone this spring, traveling to New York City to serve on the front lines of the pandemic, caring for COVID-positive patients, and counseling soldiers and family members who lost loved ones to the virus.

At the beginning of the outbreak in the spring, Major Wylie Dassie was deployed along with his Army Reserve unit out of Brockton, Mass., to New York City, where the worst of the outbreak was spreading. “Operation Gotham” saw him and his unit faced with a convention center full of sick patients and orders to nurse as many as possible back to health.

“When we arrived, there were about 550 patients there, and some were very sick,” Dassie said of the city’s Javitz Center, where the team worked 12-hour shifts with no days off. “They said we would be done as soon as the patient load dropped below 100. We were done in about six weeks.”

The convention center was divided into pods of 20 patients, cared for by Dassie and his fellow nurses. Most of his patients were between 40 and 70 years old, and the seriousness of their symptoms varied wildly.

The convention center was divided into pods of 20 patients, cared for by Dassie and his fellow nurses. Most of his patients were between 40 and 70 years old, and the seriousness of their symptoms varied wildly.

“One of the first patients I had was a woman who was just slumped over on a stretcher and was just shaking like she was having a seizure,” Dassie said. “That’s what sticks in my head the hardest. She didn’t die, but I had another patient who was the opposite. Came in walking and talking fine, and died about two days later. It was just crazy.”

As a member of a Combat Operational Stress Unit, Dassie had the additional duty of accompanying New York City police officers and medical workers to retrieve deceased patients who had died in their homes. He counseled family members in their homes, and fellow soldiers in the unit’s Behavioral Health Center.

“We helped the families and the soldiers dealing with death, talking to them about resources available and helping them get through it all,” Dassie said. “When you come off a 12-hour shift, you can talk to some people, destress, talk about some of your concerns, pick up some coffee. Just stuff that you wouldn’t think is a big deal, but it’s a huge deal.”

“We helped the families and the soldiers dealing with death, talking to them about resources available and helping them get through it all,” Dassie said. “When you come off a 12-hour shift, you can talk to some people, destress, talk about some of your concerns, pick up some coffee. Just stuff that you wouldn’t think is a big deal, but it’s a huge deal.”

Dassie also served as a public relations officer for Urban Augmentation Medical Taskforce 3 of the 804th Medical Brigade, granting interviews to media members and serving as a liaison between the Army and the press. His multifaceted experience gave him a unique perspective on the scope of the fight against COVID-19.

“Some people take it as a joke or a political hoax. It’s not,” Dassie said. “If people followed the rules and did what they were supposed to, it wouldn’t be as bad as it is now. If more people were responsible, it would be a lot better.”

After six weeks caring for hundreds of ill patients, Dassie spent two weeks in quarantined isolation before being allowed to travel back to Rhode Island. But his work may not yet be done. After a regularly scheduled two-week training drill in August, Dassie was anticipating a call back to New York in the fall.

After six weeks caring for hundreds of ill patients, Dassie spent two weeks in quarantined isolation before being allowed to travel back to Rhode Island. But his work may not yet be done. After a regularly scheduled two-week training drill in August, Dassie was anticipating a call back to New York in the fall.

“The mission was an experiment to see how we would do it the next time,” Dassie said. “They said, ‘the mission was successful; you did the job. Be prepared to come back in September.’ That’s what we were told when we left. So I might be back.

While battling an unknown enemy like the coronavirus is “terrifying,” Dassie said he wouldn’t hesitate to serve, and neither would most health care professionals.

“I was terrified like everybody else. It was very scary not knowing what was going on,” he said. “I was just an average civilian on the outside, just seeing what I’m seeing on the news. I’m sitting at home protecting myself like I’m supposed to and now all of a sudden I’m surrounded by people with COVID-19.

“I was terrified like everybody else. It was very scary not knowing what was going on,” he said. “I was just an average civilian on the outside, just seeing what I’m seeing on the news. I’m sitting at home protecting myself like I’m supposed to and now all of a sudden I’m surrounded by people with COVID-19.

“Nursing is a calling,” he continued. “We all just jump in and do what needs to be done. We had people coming in from private practice and now all of a sudden they’re changing bedpans. It was a real change for a lot of the folks coming in because we needed bodies. It’s all for country.”