Alcohol Use Disorder is among the leading causes of preventable death in the United States, killing more than 88,000 people a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control, more than HIV/AIDS, gun violence and car crashes combined. Despite this, the current medications available to treat alcohol use disorder are not highly effective.

Alcohol Use Disorder is among the leading causes of preventable death in the United States, killing more than 88,000 people a year, according to the Centers for Disease Control, more than HIV/AIDS, gun violence and car crashes combined. Despite this, the current medications available to treat alcohol use disorder are not highly effective.

A University of Rhode Island College of Pharmacy Professor is working to change that. Fatemeh Akhlaghi, PharmD, PhD, professor of biomedical and pharmaceutical sciences, is part of a team working to develop a novel medication to treat alcohol use disorder. Funded by a $1.65 million grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, a branch of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Akhlaghi’s team at URI is testing the safety and efficacy of a drug originally developed by Pfizer to treat obesity and diabetes. The grant formalizes a partnership among Akhlaghi, Pfizer and Lorenzo Leggio MD, PhD, MSc, chief of the Section on Clinical Psychoneuroendocrinology and Neuropsychopharmacology, a NIH intramural laboratory jointly funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

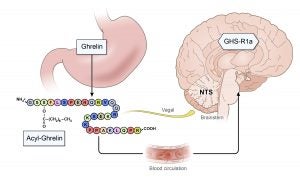

The drug focuses on ghrelin, a peptide with 28-amino acids which stimulates appetite and food intake. Known as “the hunger hormone,” endogenous ghrelin levels and feelings of hunger increase in tandem. In those suffering from alcohol use disorder, higher concentrations of ghrelin are associated with higher alcohol craving and consumption. The researchers believe that an oral medication that blocks ghrelin may help stave off the cravings for alcohol. The initial study has shown positive results in lab rats and in 12 patients who volunteered for a study at NIH. The result of this study was published in May 2018 in Molecular Psychiatry, a prominent journal in the field of medicine.

“Addictions share similar pathway in the brain — food addiction, alcohol addiction, drug addiction. If this drug can block the ghrelin receptor, even if you have high ghrelin level, your ghrelin receptors become numb, and do not respond to hunger signal,” said Akhlaghi, co-principal investigator on the study. “In 12 patients, there was a statistically significant reduction in alcohol craving and food craving. The main outcome was that the drug was safe and well-tolerated, did not affect alcohol pharmacokinetics, and that there was a significant dampening of the effect of ghrelin.”

The researchers are now working on a larger placebo-controlled clinical trial which will further test the medication on patients with alcohol use disorder. Researchers will study the effect of this  medication on patients’ alcohol cue response using functional magnetic resonance imaging to determine whether the drug has adequate efficacy for treating alcohol use disorder.

medication on patients’ alcohol cue response using functional magnetic resonance imaging to determine whether the drug has adequate efficacy for treating alcohol use disorder.

“The drugs that are available to treat alcohol use disorder either came from opioids or other drugs that make you have an aversive effect if you drink, and each of them has only small effects,” Akhlaghi said. “The study with the 12 patients shows potential success, although the results are clearly very preliminary and in need for replication. In the new phase, we are looking at the efficacy of the drug. We cannot say this is a cure; we can say it is a promising therapy.”

Click here for more information about the new clinical study.