Pandemic policy parallels: Rhode Island perspective

By Catherine DeCesare, Department of History: Applied History Lab

The second wave of the influenza pandemic of 1918-19 struck Rhode Island in the late summer and continued through the fall. As people and communities grappled with the emerging public health crisis, the confusion, shortages and unknowns certainly paralleled other communities in the US. It was a time of fear and of death situated in the midst of World War I. At the same time, the outbreak of influenza in 1918 provides historical context and lessons for today’s pandemic COVID-19 crisis. The rapid spread of the disease and associated fears, the medical unknowns and the lack of a vaccine, public health initiatives, the role of the government at the federal, state and community level to tackle the crisis, and the impact on individuals and families-physically, emotionally and economically were all relevant issues in 1918, and no different from the concerns of people living today.

The history of influenza locally, in Rhode Island was intimately connected with the history of World War I. The US entered World War I in April 1917, and mass military mobilization and propaganda (fake news) followed. News about the war dominated the front pages of the newspapers. The free press was not so free during the war years; the US government mandated unquestioned patriotism in support of the war. This control of information served to suppress negative reports on many levels, including information about the pandemic. Consequently, printed reports and certainly the headlines were often written with a positive spin, deliberately in an effort to not increase fear among the people. In light of government censorship, beginning in the late spring and early summer of 1918, reports emerged about an illness and associated deaths from a strange new type of disease – eventually known as the Spanish Flu, Influenza or Grip. Summer 1918 saw an increase in reports about influenza, but there was little sense of alarm.[1]

By late August, the disease made its way via navy transport ships to the port of Boston, on September 11, 1918 the Providence Journal reported “Outbreak of Grip at Boston Grows 1109 Cases Since Aug. 28. [and] 20 Deaths Among Sailors.” The disease quickly spread, first to Newport, RI and secondly to the Massachusetts military base at Ft. Devens, located near Worcester. The virus crossed over to the civilian population, and travelled via community spread up Narragansett Bay. Soon it was everywhere– from the East Bay, West Bay, and northern parts of Rhode Island in the Blackstone Valley to South County- including the small community on Block Island.[2] Congested, poor urban populations were disproportionately impacted, as were crowded military bases with new recruits. Influenza moved quickly, had many symptoms- case by case, and especially attacked young adults.[3]

Hospitals, doctors, and nurses were quickly overwhelmed and in short supply. In early September at the start of the crisis in Newport “With more than 700 sailors in the Second Naval District at Newport suffering from Spanish influenza, conditions at the naval hospital became so crowded yesterday morning that Commandant Oman ordered the barracks vacated and used for hospital purposes.” Sick navy men were transported to Providence hospitals. Soon, many new cases were divided between Rhode Island Hospital, St. Joseph’s Hospital and the City Hospital. [4] Public health officials repeatedly advised, “keep away from crowds, the fingers are great carriers of germs, keep them away from nose and mouth… and if you have… [influenza] stay at home so as not to spread the disease.”[5]

What started in Newport quickly became a public health issue with deaths reported all throughout the state. Some communities were quick to respond; others hesitated. There was virtually no coordinated or effective state effort. Government leaders and businesses recognized the economic impact, and some delayed initiating protocols to mitigate the spread. Republican Governor R.L. Beeckman met with the managers of various entertainment venues including the Providence Opera House, and it was determined that “If the situation assumed greater proportions later, which is not expected, then some steps can be taken for radically restricting public assemblages…”[6] Loss of income, revenue and support of the war effort were important considerations in conjunction with the public health crisis. Although health authorities advised, “Immediate closing of theatres, churches, schools and other places of assembly,” the recommendations were not heeded and in late September “deemed unnecessary.”[7] So, public events and gatherings continued in some parts of the state, and especially in the city of Providence

Notably, Liberty Bond rallies to support the war effort continued. On the evening of September 29, 1918, there was a mass meeting at the Strand Theatre in Providence to promote Liberty Bond sales. The meeting was presided over by former Senator Henry F. Lippitt, along with Harry Parsons Cross and other politicians and labor leaders. Insurance companies, banks, industrial committee members, and members of the Woman’s Liberty Loan Committee made substantial pledges for the Rhode Island campaign. Plans were drawn to “reach every one of the 80,000 employees in the 1300 industrial establishments in Providence,” in a coordinated effort to educate the workers on the need to purchase “every dollar’s worth of bonds they can swing.”[8] The following day, it was reported that more than 3000 attended this meeting, “crowded into [the] Strand Theatre.” [9] Patriotism was expected, and Lippitt’s speech identified a government list recording the donor names and the dollar values of specific contributions- those that pledged $500.00, a significant sum in 1918. However, he noted not all contributed a sufficient amount, “There are the names of some slackers there – for a man who evades the loans is just as much a slacker as the man who evades the draft…patriotism is not how you feel, but what you do.”[10]

Unlike Providence, Newport responded quickly to the crisis on September 26,1918 and city leaders closed the schools and revoked all licenses for entertainment.[11] Additional communities followed and by the end of September many Rhode Island public school systems were closed or seriously considering closure. Providence city officials yet unconvinced, believed that “the epidemic can best be fought by personal precautions and that closing schools would be even more harmful than leaving them open.”[12]

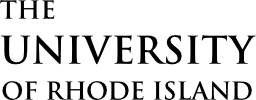

As the disease spread, events were cancelled or postponed. Dances, sporting events and even the Women’s Christian Temperance Union’s (W.C.T.U) State Conference in Newport was cancelled. Also postponed was the start of the fall semester at the State College (URI) in Kinston and the Normal School (RIC) in Providence. State College President Howard Edwards announced “Under instructions from the War Department as a precautionary measure in the national influenza situation…in consequence, it has been decided to defer the opening of the College in ALL DEPARTMENTS.” [13]

(Providence Journal, Sept. 30, 1918)

(Providence Journal, Sept. 30, 1918)

By September 27, 1918, the number of people stricken with influenza was a growing problem. The State Board of Health voted to ask Governor Beeckman to “issue a proclamation ordering the closing of all amusements places in the state, including theatres, moving picture houses and dance halls…it was further decided by the board that all questions of….closing schools or churches…should be left to the discussion of local health authorities with a recommendation that all church services be limited as to duration and frequency.” However, this plan of action never materialized as it was opposed by Providence city leadership, including Democratic Mayor Joseph H. Gainer and Providence’s Superintendent of Health, Dr. Charles V. Chapin. The Providence Superintendent of Schools “declared there is no reason for closing the schools here.”[14]

Rhode Island’s serious political divisions served to hinder a collaborate public health initiative within the state. Until the “Bloodless Revolution of 1935,” the Republican Party controlled much of the state by managing votes in the General Assembly. The state Senate disproportionately represented rural Rhode Island communities at the expense of urban ethnic communities. Elected democrats had minimal power to effectively govern, and immigrants were unable to vote. Rhode Island had the political reputation of “A State for Sale.”[15] Policy inconsistency, political turmoil, and the lack of a coordinated federal and state public health effort resulted in lost lives. All of Rhode Island was impacted, but Providence most especially.[16]

Rhode Island grappled with the growing crisis, and a state conference was called by Dr. John Keefe, medical director of the Rhode Island Council of Defense. As a result of this conference, on October 4th, medical professionals strongly urged, “that the disease may be best combated by closing schools, churches and place of amusement.”[17] The US Surgeon General identified “Drastic Closing” as the only way to stop the spread of the disease, but he noted, “There is no way to put a nationwide closing order into effect, as this is a matter which is up to the individual communities. In some States, the State Board of Health has this power, but in many others, it is a matter of municipal regulation.”[18]

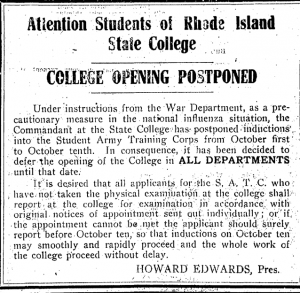

During the first week of October, the emergency exponentially expanded and the number of new cases and deaths increased. The city of Providence was especially impacted, with “6746 Cases in Providence Since Last Thursday.”[19] Providence was home to 41.3 percent of the state’s population, and it had a large and very diverse immigrant population living in identifiable neighborhoods.[20] On October 5th the Board of Aldermen acting under the direction of the Board of Health finally ordered places of public assembly to be closed and new restrictions were placed on theatres, schools, and churches. The following week, additional city services were suspended, including retail stores and street cars. Absent from this list of mandatory closures were the saloons and soda fountains. The Mayor and Aldermen decided that “they had gone as far as possible at the present time.” A much different public policy was proposed and put into place in other communities, such as Newport and in neighboring Boston, the Board of Health ordered all of the saloons, pool hall, slot machines and soda fountains closed. [21]

(Providence Journal, Oct. 11, 1918)

(Providence Journal, Oct. 11, 1918)

To address the severe shortage of supplies, equipment and medical personnel and especially nurses in the city of Providence, the Board of Aldermen allocated funds to “secure additional nurses and hospital equipment.” A committee was formed which included Dr. Chapin to immediately expand hospital facilities. “We are facing a very grave situation, this disease is likely to spread next week and by the end of the week we may have many more cases,” declared Chapin. Hundreds of physicians reported to Chapin that the disease was on the rise all over the state.[22]

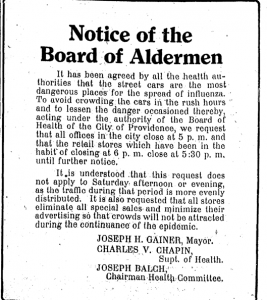

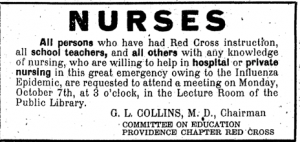

Anyone with medical experience was called upon to do his or her duty. Precautions increased, and wearing gauze masks was made mandatory for everyone that came in contact with infected people.[23] Over the next few days, as the crisis continued and fatalities increased, doctors and nurses were “worn out by attendance on patients,” and some physicians and nurses exposed to the disease died as well. Most critical was the demand for nurses, and the Red Cross in a meeting held at the Providence Public Library recognized and advocated for “amateur nurse [so] the trained nurse can be relieved to attend to the more serious cases.” The Providence Public Library, in response, to this need and after consulting with medical professionals, increased the number of books on nursing at the library. [24]

(Providence Journal, Oct. 3, 1918)

(Providence Journal, Oct. 3, 1918) (Providence Journal, Oct. 7, 1918)

(Providence Journal, Oct. 7, 1918)

Rhode Island businesses were hit hard by the disease. In addition to the mandatory closures, additional shops closed. Some shut down due to the sickness of the labor force. One example was the Stillwater Worsted Company of Harrisville. It closed on Oct. 7, 1918 because so many of the employees were ill with influenza. Production for World War I was in full force, and many of the Rhode Island manufacturers were producing for the war effort. As a result, on Oct. 8th. Army Major C. G. Williams, issued the following directive, “Influenza is interfering with our munitions plants…it is up to the men and women who are still on the job to make good the loss of the comrades. Speed up. Your country needs every bit of your energy today for the men in France.”[25]

By the middle of October, reports emerged about the decreasing threat of influenza. “Peak of Epidemic is Believed Past Influenza Situation in State Shows Steady Improvement.” Businesses, schools, clubs and organizations started to reopen, including the Rhode Island State College in Kingston. However, public health officials, including Dr. Chapin continued to recommend precautions to safeguard against Influenza. Not only was the advice directed at influenza avoidance, but he promoted good nutrition, exercise, sleep, and “above all, leave alcohol alone and keep out of bar rooms.” Even as late as December 1918, Chapin continued to place influenza prevention notices in the Providence Journal. Although, the second wave of influenza declined by late fall 1918, the third wave was on the horizon and erupted in the spring of 1919.[26]

Unprecedented is often used to describe today’s COVID-19 crisis. It might be extraordinary now, but past generations tackled similar issues. Some circumstances are different today, but the context remains. The absence of coordinated state and federal action to fight the 1918 pandemic, mirrors the impotence seen at the national level today. Currently, states and especially governors are tasked to manage the crisis within their own borders. Some states, Rhode Island included, are proactively addressing challenges- but others are not. Is this sufficient?

The failure of the federal government, especially early on, to mitigate COVID-19 is a byproduct of decentralized federalism.[27] Additionally, our deeply divided political reality accentuates the lack of a coordinated disaster policy, and identifies the glaring absence of a national health care system.

History is important, and the past can help inform policy initiatives today.