Nature is full of surprises. That’s one thing I love about venturing out; you really never know what new thing you may encounter. And then, in addition to the wonder of discovery, it’s fun to speculate why this?, why now?, and how might this be important? These questions have pre-occupied my thoughts for the past several weeks, because while out in the woods collecting adult stage blacklegged ticks this autumn, for the first time in about a decade and a half, I was encountering winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus), more commonly referred to as the moose tick.

I’m somewhat familiar with this tick, having recovered it once or twice on the Elizabeth Islands back in the 1980s, and twice in Rhode Island in the early 1990s. Winter tick is a curious one, different from the ticks we’re all more familiar with like the blacklegged tick and the American dog tick. Winter tick is called a one-host tick in that all active life-stages—larvae, nymph, and adult—infest and typically remain attached to the same individual host. And commonly, that host is a moose, which is why this tick is best know as the moose tick.

Moose ticks have been making the news in some circles (http://bit.ly/mooseticknews) most recently as yet another bellwether of climate change. Moose populations are increasingly taking a hit as this tick, once considered a rare stressor, is now a potential population disrupter because of delayed and warmer winters.

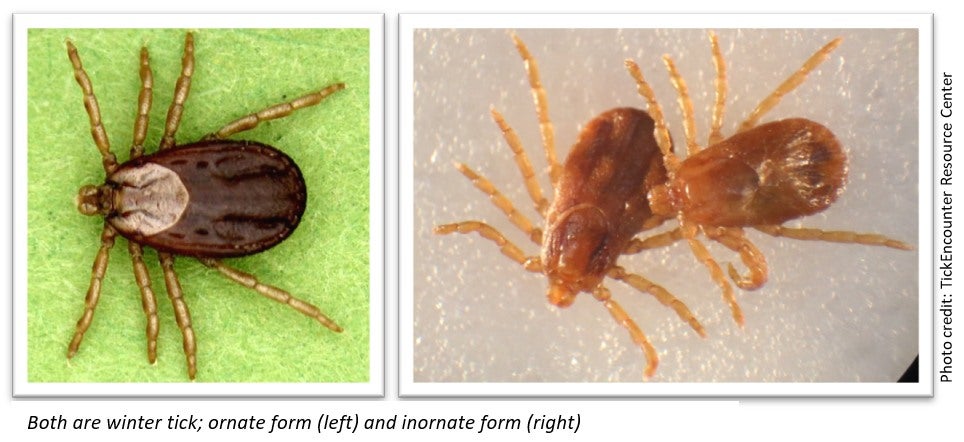

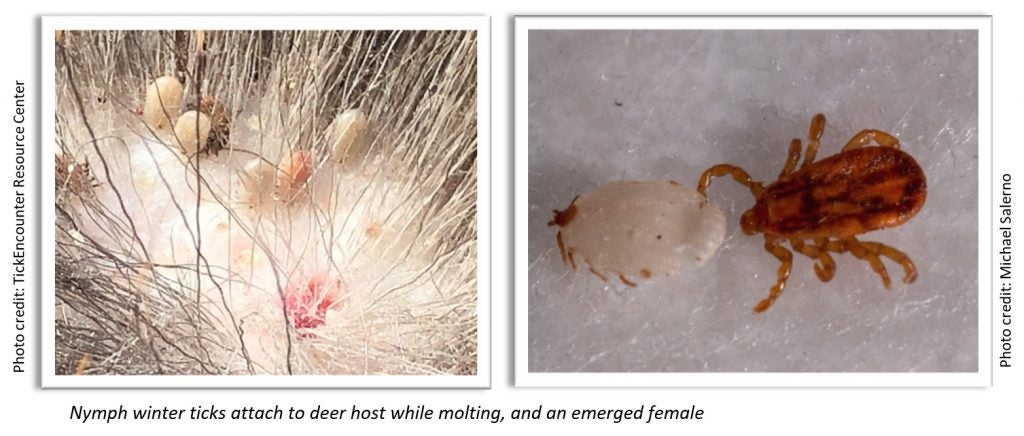

The typical lifecycle of winter tick begins with larvae climbing aboard their host in September and October, blood-feeding and remaining attached as they transform into the nymph stage that emerge from a cocoon-like form, and then re-attaching to the same host. This process repeats itself but this time, the ticks emerging from the cocoon-like form, usually in late winter, are male and female adult stage ticks. Adult ticks attach and then engorge on hosts typically at the end of winter—late March, early April in the North Country (typically states and provinces along the border). That last large bloodmeal taken by thousands of attached adult ticks is what pushes the heavily tick-infested moose from a state of chronic anemia experienced from January to March into an acute and often-fatal anemia in the last weeks of its life. At least, that’s the story of winter tick on moose.

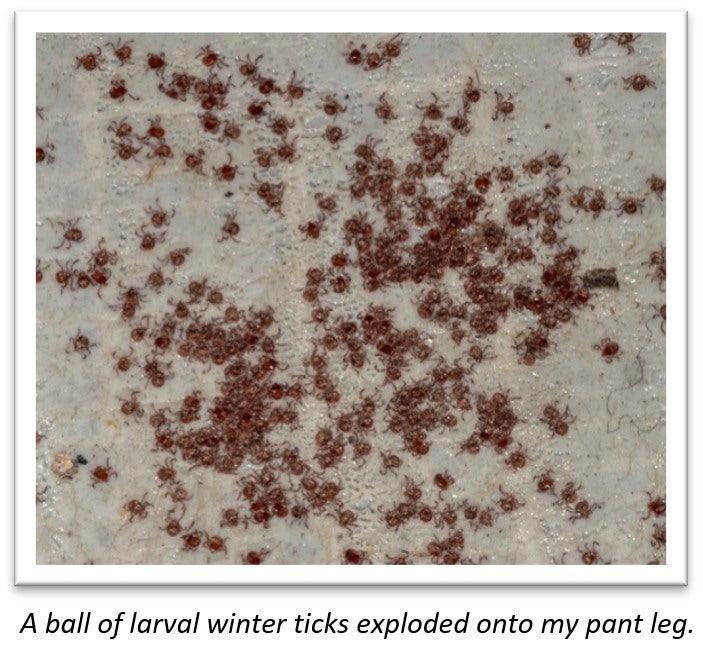

In addition to moose, the winter tick actually is an important pest of horses, cattle, elk, and deer in the northern and western U.S. and Canada. But just to make the story a bit more confusing, there is a smaller variant form of this tick more common in the south and east regions, and once even called the brown winter tick, being formerly recognized as a separate species (D. nigrolineatus). Its taxonomic status is now merged together with the larger D. albipictus as all the same species. The potentially confusing part of this is that these two ticks look different, and behave a bit differently as well. Studies have documented that where their ranges collide, they can interbreed and produce viable offspring. But the molecular testing of these two forms to assess their relatedness throughout their ranges has not yet been accomplished.

So, just how different are these ticks besides their size? The most noticeable difference is that while the larger form (we’ll call those moose ticks) has white pigment on its scutum (referred to as ornate), the scutum of the smaller form lacks pigment (call it inornate).

Both forms are one-host ticks, latching on as larvae, and locking in on the same host through two more molts. But I found it quite amazing, and unexpected, to find all three active life stages of the inornate form (larvae, nymphs, and adults) on a hunter-killed deer in November. That’s

not what happens with the ornate form on moose. Those ticks need to stretch out their time on the host so that they don’t get stranded on the cold snow pack by detaching too soon. The adult females of the inornate form, however, were engorging and detaching, and even laying eggs, before winter even really set in.

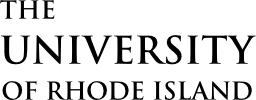

Back to my questions, why here and why now? I’m not sure. But this was more than just a quirky Rhode Island phenomenon this year. While I found winter tick at all of my regular Rhode Island tick collecting spots, I also encountered them while collecting blacklegged ticks on the south shore of Boston; and colleagues were surprised to find them in western Connecticut and New Jersey, too. To the significance of all this…well, time may tell. It was truly a surprise for me as 15 years had passed since the last time I encountered these ticks in the wild, and then, only in one isolated spot. This year, I had dozens of encounters with larvae ‘bombs’ in many areas suggesting that something was different. Normally, deer do not experience the same level of infestation that is causing declines in the moose population, but when nature speaks, I believe it’s always a good idea to pay attention.