For The Flower District, a bustling nonprofit in Olneyville, Providence, physical space needs to serve a variety of purposes. Their team grows and rescues over 100,000 flowers annually to distribute to local hospitals, hospices, food pantries, senior services, recovery centers, shelters, and people who could use some cheer.

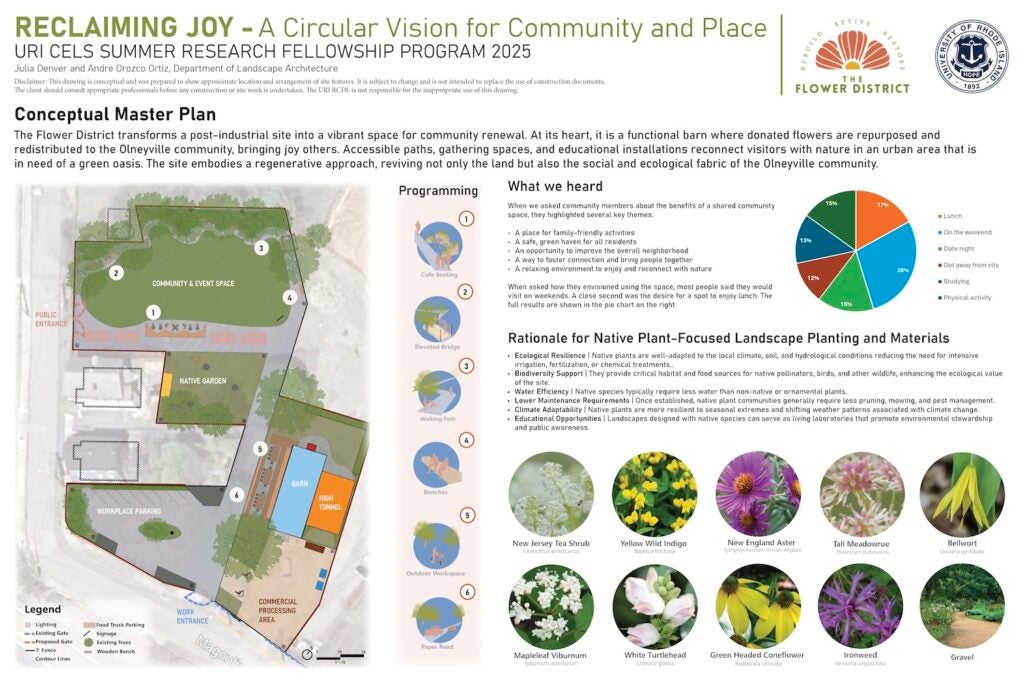

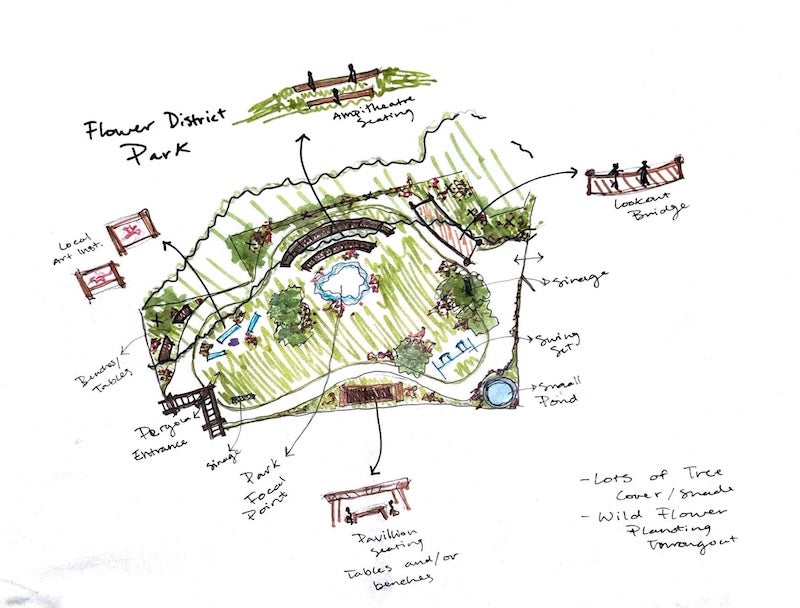

Set within a post-industrial landscape surrounded by factories, the organization’s site presented a unique challenge and opportunity for Julia Dever and Jose Andre Orozco Ortiz. The two landscape architecture majors spent their summer using both hand-renderings and computer graphic software to design a community green space for The Flower District as part of the CELS Summer Research Fellowship program.

Their mission was to create a dual-purpose environment that would balance aesthetics with functionality: a practical workspace for staff and volunteers and a welcoming green space for private and community events. In addition to growing flowers, the nonprofit also offers a variety of programs–from educational to job training.

“The Flower District is embedding sustainable floristry within a circular economy framework, aiming to influence the cut-flower industry toward more sustainable practices while maximizing community participation and benefit,” says Jane Buxton, program director of the Department of Landscape Architecture. “A circular economy reduces waste and pollution, optimizes the reuse of products and materials, and supports the regeneration of natural systems.”

“This way of thinking aligns with the work of landscape architects,” she adds, “which goes beyond aesthetics to see each place as shaped by interconnected environmental and historical systems, from ancient geology and hydrology to ecology, human influence, and future impacts.”

Dever and Ortiz embraced the design challenges. “Beyond spatial utility, we were keeping in mind the organization’s mission; centered on sustainability, reviving, rebuilding and restoring, and using thoughtful design elements to tell their story,” Dever says. “The most surprising aspect has been how much storytelling is embedded in spatial design. Every corner, pathway, and material choice can reflect the values of the organization, something I hadn’t fully appreciated until diving into this project.”

Ortiz helped by translating community input and operational needs into a functional site design for the Flower District’s flower recycling and composting program. “The most challenging part has been coordinating all moving parts, getting different inputs from mentors, board members, the community and interested parties and creating something that could please everyone,” he says.

“The most surprising thing was accepting that not everything goes as planned,” he adds. “The most rewarding was acknowledging that I was part of something much greater than just me.”

Dever notes that working alongside volunteers and staff at the organization who are passionate about their work and committed to community enrichment was inspiring and meaningful. “Translating the nonprofit’s mission into a physical space, where every design choice supports healing, growth, and connection was a unique challenge that pushed artistic boundaries,” she says. “Watching initial sketches evolve into tangible plans through hand rendering and digital tools was deeply satisfying. It’s one thing to imagine a space but it’s another to see it begin to take shape.”

Bridging real-world application with academic concepts and theories is an integral part of education, the students note. “It introduced me to new ways of thinking,” Ortiz says of practical skills they developed, such as site analysis, human-centered design, mission-driven spatial planning, programming, and proficiency in both hand-rendered and digital tools.

“Collaborating with a nonprofit and designing for community impact has shown me how landscape architecture can be a powerful medium for social connection and storytelling,” Dever adds, “far beyond aesthetics alone.”

“André and Julia balanced the need for timely results with community engagement, collaborated with the nonprofit’s board, developed skills in site analysis, drafting, and rendering, and deepened their understanding of the connections between people and place,” says Buxton. “They are thoughtful, talented students; I am proud of their work and eager to see their future contributions to the field.”

The students look forward to the next step in their project: presenting their design to stakeholders and receiving feedback for possible implementation. “I’m excited to engage in meaningful dialogue, receive feedback, and see how our work can inspire real change and connection within the Olneyville community,” Dever says.

“The best reward is knowing that the space will foster connections and serve as a hub for inspiration and collaboration,” she adds. “It’s not just a design—it’s a living environment that will grow with the community.”