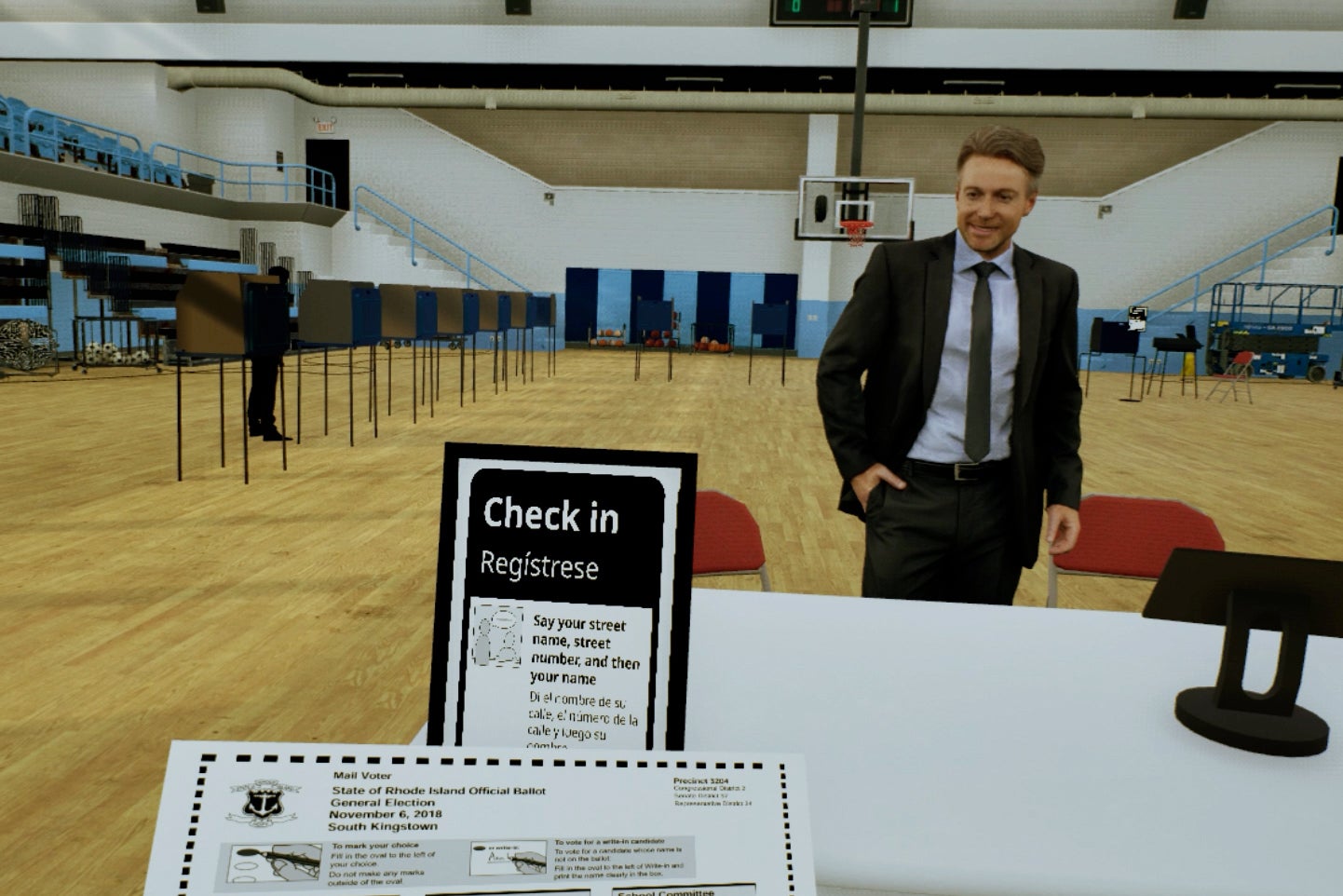

In a recent pilot project, we partnered with the Center of Civic Design for a pilot study to use VR to test how voters interact with polling place signage in a simulated environment. Over the course of one day, 14 student participants navigated a virtual polling place while researchers observed their behavior and gathered qualitative and quantitative data.

The study revealed that clear signs and their placement play a vital role in helping voters find their way. It also showed that VR can be a powerful tool for prototyping and improving polling place design before election day.

Key Findings

This pilot study explored how voters interact with polling place signage in a simulated virtual reality environment. As participants navigated a realistic voting setup, researchers observed how signs, spatial layout, and environmental cues shaped their experience. The findings below highlight what worked well, what caused confusion, and how signage design and placement can directly influence voter confidence, efficiency, and understanding.

1. Seeing (virtual) people helped participants navigate

Participants used (virtual) people in the space to make navigational decisions as often as they used the signs and the voting stations.

2. Arrows were universally understood to be for navigation

The difficulties reading signage text made the signs with arrows (added in Level D) more attractive and useful for navigation.

Arrows + text clearly identify a navigational sign

When a sign with an arrow was placed in the open space between the check-in tables, participants noticed it and headed more confidently to the voting booths

3. Instructions must go where voters need to use them

Instructions to say your name and address at the check-in table were misplaced when at the start of the line.

- The placement put the instructions before the decision about which table to go to

- The time to get from the end of the line to the check-in table was variable

The same sign was repeated at the table itself.

4. Signs with a clear function and message were most effective

By the final levels there were several types of signs. Participants used them in different ways.

- Arrow signs were easy to read at a distance, and were used with the moderator’s verbal cue

- Station identification signs were helpful in confirming when they reached the right location

- Many explored the notice board at the entrance, but said it was not helpful

5. The VR tool allows easy experimentation with signs

Even with a relatively simple virtual environment, participants were able to engage with the simulation.

- The virtual space was realistic enough for people to want to find the correct check-in table

- Adding complexity each layer allows us to try different things, and learn what is needed for a realistic simulation

- The environment was effective in visualizing spatial relationship, which was helpful to understand how far away things are, how large signs might need to be, and where more signs might be needed to maintain a continuous visible pathway

About the Research

This research was conducted by Gretchen A. Macht, Ph.D., and Amber Fearn from the Engineering for Democracy Institute and University of Rhode Island students Collin Batchelor, Ryan Benvenuti, Kirk Brown, Shubham Chomal, and Malinda Fry in partnership with Tasmin Swanson, Evie Lacroix, Randy Hadzor, and Whitney Quesenbery from the Center of Civic Design.

We used Rapid Iterative Testing and Evaluation (RITE) as our research method. Every 2-4 participants, we updated the VR environment to address problems identified by the most recent participants.

Through the six levels (or scenarios) we added people — both voters and poll workers — added objects, and enhanced the interaction with the ballot.

As the virtual polling place got more realistic and crowded, the pathways participants took became more varied.