By Lauren Rebecca Thacker

Taking action to combat climate change is no longer a question of “if.” It’s “when.” Offshore wind—a source of clean, renewable energy that can power hundreds of thousands of homes—offers great potential for Rhode Island, and the nation overall, to meet its stated goals for reducing carbon emissions. Meanwhile, as wind farms off the coast of New England move forward, oceanographers and policy-makers work to ensure marine life, habitats and livelihoods are protected.

The United Nations recently issued a call to “rapidly accelerate” efforts to combat climate change and advocated for a threefold increase in renewable energy by 2030. That is a big year for the federal government’s goals—by then, it aims to power federal facilities with 100% carbon pollution-free electricity and deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind, enough to power 10 million homes. This dovetails with Rhode Island’s goal of running on 100% renewable energy by 2033 while growing the blue economy. The state is home to the country’s first commercial offshore wind farm, a five-turbine farm off the coast of Block Island, and more are in the works.

The United Nations recently issued a call to “rapidly accelerate” efforts to combat climate change and advocated for a threefold increase in renewable energy by 2030. That is a big year for the federal government’s goals—by then, it aims to power federal facilities with 100% carbon pollution-free electricity and deploy 30 gigawatts of offshore wind, enough to power 10 million homes. This dovetails with Rhode Island’s goal of running on 100% renewable energy by 2033 while growing the blue economy. The state is home to the country’s first commercial offshore wind farm, a five-turbine farm off the coast of Block Island, and more are in the works.

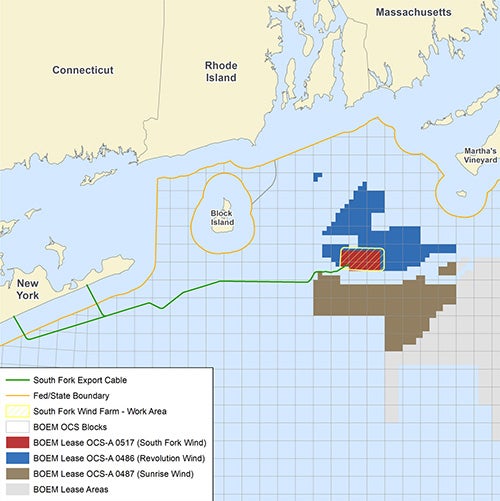

At the time of this writing, plans in the region include Revolution Wind (about 15 miles south of Point Judith), South Fork Wind (between Block Island and Martha’s Vineyard), and Vineyard Wind (about 15 miles off the coast of Martha’s Vineyard). Three New England states—Connecticut, Massachusetts and Rhode Island—recently signed a Memorandum of Understanding to combine their purchasing powers and lower construction costs. Revolution Wind has proposed 65 wind turbines and two substations, which could power approximately 250,000 homes and create 1,200 local jobs during the construction phase, according to the Department of the Interior. South Fork Wind, which is expected to start up very soon, is slated to power more than 70,000 homes, while Vineyard Wind I, under construction now, plans for 62 turbines that can power over 400,000 homes. Nationally, there are plans for offshore wind farms in the Gulf of Mexico and off the West Coast.

The Urgency

Christopher Kearns, B.S. ’08, acting energy commissioner for Rhode Island, says that the state’s objectives for renewable energy stem from state laws that have been adopted over the past 15 years. Offshore wind, which has been growing in Europe for over a decade, is part of the plan.

Meeting that goal means acting now.

“These projects take a long time,” says Kearns. “The Block Island Wind Farm took almost a decade to move from the concept to being commercially operational. The pending R.I. Revolution Wind project received one of its final federal approvals this summer. Seven to eight years will elapse from the start of the project procurement effort in 2018 to becoming commercially operational in late 2024 or 2025.”

Jaime Palter, associate professor of oceanography, does not dismiss concerns about the impact of wind farms on marine life. But, she points out, marine life is already at risk due to warming oceans. The ocean, which absorbs 90% of the heat generated by greenhouse gas pollution, acts as a shield against the impacts of climate change. Its immense size, however, makes it slower to warm compared to the air. But still, the ocean is warming, particularly near the surface, which results in some widely-known effects like sea level rise that stands to engulf culturally and economically significant coastal areas.

“So creatures like Atlantic cod run out of suitable habitat, as they use more of their energy to breathe. It adds up—the warmer ocean depletes oxygen and these animal’s metabolism responds by speeding up and demanding more oxygen, leading to huge stresses for these populations.”

Warming oceans have also caused changes to the geographic spread of marine animals. The northward shift of lobster stocks provides an example of why we need to act now to combat global warming and preserve marine creatures and those whose livelihoods depend on it—and why offshore wind is a potential solution fraught with concern.

The American Lobster is fished in U.S. waters from the Carolinas to the Gulf of Maine, where it remains abundant. The economic impact of lobsters in Maine is huge: more than 100 million pounds is harvested each year by more than 5,600 lobstermen. The Maine Lobster Marketing Collaborative estimates that the industry contributes more than $1 billion to the state’s economy on an annual basis.

But the Gulf of Maine is rapidly warming. It’s warming three times faster than the global average in fact, increasing at a rate of 0.8 degrees Fahrenheit every 10 years for the past four decades. The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that the lobster population has already diminished in southern New England and that warmer waters and the increased metabolic demands that Palter points to have diminished stocks and present an ongoing threat.

It stands to reason, then, that in order to preserve the lobster population and the lobstering industry, there must be interventions. If offshore wind farms decrease reliance on fossil fuels and mitigate continued warming effects, then it’s good for lobsters. Right? Well, it’s not so simple.

Anna Mercer, Ph.D. ’15 explains the catch-22 of offshore wind development, saying, “We need offshore wind to become less reliant on fossil fuels. But, anytime we’re developing something new in the oceans, the faster we do it, the higher the risk.” Mercer, who is the cooperative research branch chief for the Northeast Fisheries Science Center at NOAA, adds, “We need green energy that does not jeopardize the health of our ocean ecosystems and the productivity of our fish stocks, which is the last source of renewable protein in the entire world. So, there’s a lot at stake.”

The Concern

“We need green energy that does not jeopardize the health of our ocean ecosystems and the productivity of our fish stocks, which is the last source of renewable protein in the entire world. So, there’s a lot at stake.”

Anna Mercer, Ph.D. ’15

For comparison, the Biden administration has a goal of having 30 gigawatts of offshore wind energy by 2030; Europe currently has capacity for 28 gigawatts of energy from 123 wind farms in 12 countries. This means there would be more wind turbines appearing in U.S. waters in the next 10 years than were built in Europe over the last 40 years. All current and proposed wind farms in the United States are within the continental shelf, which is wide on the East Coast and relatively narrow on the West. Reaching the 30 gigawatt goal will necessarily involve a dense concentration of wind farms on the shelf–more dense than in Europe’s North Sea–and the advent of deep sea wind farms.

Wind farms in Europe and more locally, at Block Island, do provide preliminary evidence of the effects of wind turbines on some marine animals, such as mussels and crustaceans, but questions remain.

Jeremy Collie, professor of oceanography, says, “There is some evidence that the foundations of turbines act as an aggregating device that some species may be attracted to. We can call that a spatial effect—more animals congregating in a smaller location. But that does not tell us about the overall effect on the population. Is it a net gain or a net loss?”

This is only an example of the many unknowns.

“What are the impacts? That’s the big question. We’re ramping up research programs so we can determine the answers,” says Mercer. “For example, when considering hundreds of turbines rather than the five at Block Island, there can be impacts on currents and movement, particularly for fish and sharks that use electromagnetic frequencies to identify their prey.”

The Connections and Collaborations

Discussions about offshore wind energy must recognize the interconnectedness of ocean and land ecologies, says J.P. Walsh, professor of oceanography and director of the Coastal Resources Center (CRC). “Any action in the ocean can affect humans, and vice versa. The Coastal Resource Center directly engages coastal communities—a community could be people who live in a certain town or it could be people who work as fishermen or in the tourism industry.”

Mercer echoes this idea. “Understanding the impacts of offshore wind on the ocean ecosystem in our coastal communities is an interdisciplinary effort, maybe more than any type of science that we do,” she says. “It requires collaboration between experts from different scientific disciplines as well as between scientists and the fishing community.”

Bethoney says that the Commercial Fisheries Research Foundation provides a model for the type of collaboration needed to answer questions like this.

“The foundation began 20 years ago to get more fishermen involved in science in order to fill gaps in data,” he says. “The board of directors are all active fisherman or work in shore-side support businesses. Now, with offshore wind seemingly imminent, we’re engaging with developers so that the fishermen, who are on the water and will be affected, have an active role in collecting data and monitoring fisheries.”

Bethoney and Collie are working on a project that monitors the lobster population in the area called the Rhode Island Massachusetts Wind Energy Area, the proposed location of the South Fork Wind Farm and Revolution Wind Farm. They have been collecting data since 2014.

Collie explains that lobsters in the area will move on- and off-shore depending on the season. Some even head to the edge of the continental shelf. The lobster population data that’s being collected now is intended to provide a baseline for comparison when the farms begin construction.

Another project in the wind farm area has Collie, Bethoney, and Hannah Verkamp, a research biologist at CFRF, collaborating with Michael Marchetti, the owner and operator of Mister G, a fishing vessel based in Point Judith. The survey is designed to describe and quantify the important fisheries species selected by beam trawl gear in the wind farm lease area, as well as reference areas, for two years prior to, one year during, and three years after the construction of the South Fork Wind Farm.

Jennifer McCann, director of U.S. coastal programs at CRC, has been involved in offshore wind in Rhode Island since the beginning. McCann, who is also director of extension for Rhode Island Sea Grant, worked on the Rhode Island Ocean Special Area Management Plan (Ocean SAMP) in planning for the Block Island location.

For Ocean SAMP, URI worked with the Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council to determine a location for the turbines that would have the least impact on people and wildlife. The five-turbine farm was an enormous project, considering everything from public input and tourism to ocean ecology, indigenous histories, and fishing practices, among other concerns.

Stephan T. Grilli, distinguished professor and former chair of ocean engineering, contributed to Ocean SAMP. Ocean engineers surveyed the sea floor using sonar systems to determine the best location and structure for the foundation—in Block Island’s case, he says, the foundation and underwater support structure look a bit like an underwater Eiffel Tower. Electrical engineers work on the cables that go from the turbine to the island, as well as to the mainland via tunnels under Scarborough Beach in Narragansett.

Engineers will remain key partners as deep sea wind farms with floating turbines become a reality. Grilli leads a team of researchers at URI and the University of Maine that recently received a U.S. Department of Energy grant to develop a remote sensing and computational system to control the motion of floating wind turbines in irregular ocean conditions. The system would maximize energy production and extend the turbine’s useful life.

McCann says that offshore wind needs to have a “smart growth” mindset: working to find technological, policy or economic solutions that lessen tension between different interests.

Collaboration and smart growth are important from an industry perspective, as well. Scott Lundin, M.S. ’04, vice president of permitting and community affairs at Equinor, an international energy company developing offshore wind here in the United States, stresses the importance of the local community and environmental impact questions, calling them integral to the success of any project.

McCann is part of an international project focused on collaboration over competition. The project, called MULTI-FRAME, is funded by the National Science Foundation. “A multi-use framework moves away from the idea of exclusive ownership of resources,” McCann says. “When considering the location of wind farms, we need to consider how we can create collaboration and synergies between resource uses.”

The Future

“These are some of the largest structures built by humans. They are just incredible, and they combine so many different disciplines.…offshore wind can create clean energy and jobs in our region.”

URI professor Stephen Grilli

Walsh says, “Students interested in things like offshore wind should have a broad understanding of the coupled human-natural system and how the fundamental science of the coastal ocean system relates to human activities. GSO trains students to have coastal and marine systems expertise, and the CRC, as part of GSO for over 50 years, compliments that scientific knowledge with an emphasis on connections.”

URI’s close relationship with the CFRF, led by Bethoney, allows faculty and students to be part of complex research projects that engage directly with the fishing community. Currently, the majority of the 17 active CFRF projects involve GSO faculty or alumni.

Grilli says that the United States needs domestically trained experts in offshore wind development. “In ocean engineering, we offer a senior project on wind farm design. These students are some of the only engineering students in the country to get that kind of experience and knowledge at the undergraduate stage,” he says. “We see them get hired immediately. It’s very exciting.”

That excitement captures Grilli’s overall feeling about offshore wind energy. He knows there are many problems to solve, but he marvels at how much progress has already been made, saying, “As an engineer I’m in awe. These are some of the largest structures built by humans. They are just incredible, and they combine so many different disciplines.” He adds, “It’s professionally exciting for me but it is exciting for society as well, because offshore wind can create clean energy and jobs in our region.”

Lundin says that from his point of view as a native Rhode Islander and GSO graduate, offshore wind presents an incredible opportunity to transition to renewable energy.

“I’ve been lucky enough to be near the ocean my whole life. I don’t begrudge anyone who wants to protect their community and it is easy to be focused on one cable landfall or substation location,” he says. “For those of us who live on the coast, offshore wind development may be right in our backyard. But the climate crisis will be right in our backyard, too, if it isn’t already.”

And therein lies the tension with offshore wind. If we do nothing, the climate crisis will worsen, impacting marine life and coastal communities. But if we act too quickly, those same populations could be harmed. The only way forward is to acknowledge this tension and make addressing it a priority.

Mercer puts it this way: “We can all agree that we need to meet our clean energy goals. But we need to consider ecological, oceanographic and social impacts as we move forward. Doing so will take leveraging the variety of expertise that we have in Rhode Island and committing to collaboration.”