Authors: Austyn Ramsay and Shawn Sheppard

Social Science Institute for Research, Education, and Policy, University of Rhode Island

Prepared for: Adoption Rhode Island

Spring 2021

Executive Summary

Foster youth face many challenges which lead to overall poor educational and economic outcomes. Not only do foster youth have a lower than average likelihood of graduating from high school, but data analysis from the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training found that only about 1% of former foster youth graduate with a credit-bearing certificate, associates, bachelors, or other postsecondary degrees. This low educational attainment among foster youth ends up costing the state, as low educational attainment is correlated with higher use of state social services, unemployment, and incarceration. For these reasons, the state can and should invest in foster youth educational success. In this report, we explore national data on foster youth and data from Rhode Island, as well as the academic and policy literature about the barriers to foster youth participation and success in higher education.

Recommendations

- Guarantee Every Foster Youth Can Afford College and Living Expenses by ensuring ample funding to cover all costs associated with achieving a bachelor’s degree at RIC or URI for all foster youth who are in foster care as of their 14th birthday.

- Eliminate or ease all restrictions on current funding available for foster youth pursuing higher education.

- Assign personal educational liaisons to all foster youth in middle and high school, to focus explicitly on ensuring foster youth have the support they need to succeed in school and ensure a smooth transition through their educational careers.

- Ensure all foster youth fill out the FAFSA as part of their transition plan.

- Invest in foster youth higher education completion and success by implementing programs, such as Talent Development and The First Star Academy Program, at state colleges to promote enrollment and aid the retention of foster youth in post-secondary education.

- Encourage foster youth to pursue their higher education at four-year colleges and universities to maximize their chances at educational success.

Rhode Island should not only enact the policies listed above but also widely publicize the initiatives to demonstrate the State’s commitment to and belief in the success of all foster youth. This will have the greatest impact on increasing foster youth’s perception that they can succeed by showing both publicly and internally that the State believes in the ability of foster youth to be successful both in their education and in life.

Obtaining a quality education is critical to not only becoming an informed member of society but also qualifying for and being able to work in the vast majority of jobs that pay a living wage. Unfortunately, educational attainment among foster youth is very low. Not only do foster youth have a lower than average likelihood of graduating from high school, but data analysis from the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training found that only about 1% of former foster youth graduate with a credit-bearing certificate, associates, bachelors, or other postsecondary programs.[1] This low educational attainment among foster youth ends up costing the state, as low educational attainment is correlated with higher use of state social services due to former foster youth experiencing higher than usual rates of unemployment, housing insecurity,[2] and incarceration.[3] According to the RI Department of Labor and Training, only about half of the foster youth who aged out of the system between 2006 and 2014 went on to be employed in the State of Rhode Island. However, foster youth who graduated from college earned twice the annual median income of those who only graduated high school.[4] These data suggest that supporting foster youth to pursue higher education will lead to higher levels of self-sufficiency in adulthood. However, foster youth face many barriers to participation in higher education. These challenges are unique for foster youth because they are among a minority of young adults who face paying for and navigating higher education without the emotional or financial support of family. As a result, foster youth are particularly challenged by taking the correct classes and filling out applications in high school, financing their higher education and their living expenses, understanding and accessing support services, and social-emotional wellbeing.

Moreover, young people in state care, especially those who age out of foster care without permanence, have a very unique relationship with the State of Rhode Island. Unlike other similar at-risk or underserved groups, foster youth are wards of the State, with social workers, foster parents, and community agencies filling roles that are normally filled by parents and other adult family members. Without traditional family members, foster youth are raised differently and develop unique perceptions of their abilities and worth. Foster youth are at risk of developing negative views about themselves and their abilities: views that can be extremely detrimental to their future success and life outcomes.

Foster youth are particularly at risk of what academics refer to as “stereotype threat”. Stereotype threat is when individuals do worse than they otherwise would in educational settings because they are led to believe that people like them do poorly in school.

Foster youth’s specific life position can lead to these feelings and can affect their own beliefs about their overall success in life and education. Foster youth lack the basic support at home for necessities, and especially lack positive encouragement regarding their educational and personal capabilities. However, encouragement and positive mentorship are essential for this at-risk population to achieve positive outcomes.

One of the most important findings of education psychology literature is that simply communicating to students that they are capable of achieving at high levels can increase school performance, graduation rates, and standardized test scores.[5] Being encouraged to attend college at a young age has been linked to higher outcomes of college attendance.[6] When young people believe that they have the capacity and are expected to excel they are more likely to succeed. Rhetoric that enables students to picture themselves in higher education settings affects the likelihood that the child will go to college.[7] When kids can picture themselves in educational settings, they are more likely to do well and continue to pursue education. Coupling this rhetorical effect with the actual means and resources necessary to succeed in higher education is the approach most likely to drive more foster youth students to be successful in college.

One of the key areas where the State can and must boost the chances of foster youth attending and succeeding in college is by instilling an honest sense of belief in the ability of all foster youth to have educational success. Studies have shown that in educational areas, placing high expectations on young people leads to a greater sense of belief in themselves and directly correlates with college success.[8] Guaranteeing foster youth will be able to afford higher education, expecting and facilitating FAFSA applications, exposing them to college before their senior year, and engaging them in programs that foster success while in college, not only helps foster youth in these programs directly, but this investment also will cause a systemic change by changing the stereotype of what foster youth are expected to accomplish. The state can send a message to foster youth that Rhode Island believes in their ability to achieve and expects them to accomplish their educational goals. The state can say to all foster youth “you are not your circumstance and we will invest in your success.” We believe that the State of Rhode Island should not only enact these policies but also widely publicize the initiatives to demonstrate the State’s commitment to and belief in the success of all foster youth. This will have the greatest impact on combating stereotype threat by showing both publicly and internally that the State above all others truly believes in the ability of foster youth to be successful both in their education and in life.

Recommendation 1: Guarantee Every Foster Youth Can Afford College and Living Expenses

Studies have found that affording higher education is the most significant barrier for foster youth to succeed in post-secondary education. It is imperative that youth who age out of foster care be provided with college tuition and living expense assistance to increase the educational attainment of one of the state’s most vulnerable populations. Affording college is a challenge that almost all American youth face. But while many American children, even those from disadvantaged backgrounds, can draw on family resources to offset the cost of tuition or living expenses, foster youth who age out of the foster system without being placed with a permanent family, lack these social supports, and are in a unique position: they must finance both their education and their living expenses alone. This financial requirement comes with a real cost to foster youth success in college: according to a 2005 survey, while 79% of foster youth who enroll in college are dependent on financial aid to stay in school, 76% reported that even with that aid, they struggle to find the time needed to complete their course work because they have to work over 20 hours a week to support themselves for basic needs such as housing, food, and transportation.[9] Currently, there are funds available both at the federal and state level to support foster youth attending post-secondary education, but it is not nearly enough to guarantee the necessary funding to all foster youth who wish to go to college. The Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families receive $200,000[10] per year through the DCYF Higher Education Opportunity Grant to help offset the costs of tuition for former foster youth. In addition, students can also apply for funds through the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program, a federal program that provides up to $5,000 per year from the federal government to foster students to assist with college tuition. These funds are not adequate to meet the out-of-pocket cost of attendance and living expenses even when taking into account potential additional financial resources such as Pell Grants, Federal Student Loans, and Federally subsidized grants from the Chafee Foster Care Independence Program.

Figure 1. Cost of Attendance for Two RI Colleges

| College | Pell Grant (Per Year) | Chafee Funding (Per Year) | Tuition (Per Year) | Housing – on campus Academic Year | Housing-on campus Summer | Meal Plan (Per Year) | Other Fees (Per Year) | Unmet Costs** |

| University of Rhode Island | $6,345 | $5,000 | $12,590 | $8,582 | $3,110 | $5,695 | $1,976 | $20,608 |

| Rhode Island College | $6,345 | $5,000 | $10,260 | $7,210 | ~$2,600* | $5,137 |

$1,200 |

$15,062 |

| ** (Total Tuition, Housing, Meals and “other fees” after Pell and Chaffee Funding Reduction) | ||||||||

Figure 1 shows the approximate costs of attendance per year for The University of Rhode Island and Rhode Island College including housing and a food plan. The DCYF Higher Education Grant can only cover the full remaining out-of-pocket cost for 9 students per year attending the University of Rhode Island and/or only 13 students attending Rhode Island College. According to the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, and Families, approximately 17 foster youth age out of the system without permanency each year.[11] Given the Higher Education Opportunity Grant is also available to children who were in foster care at some point in their lives, not just those who age out of the system, this funding is much less than what is needed to guarantee all foster youth can afford college. The State of Rhode Island should ensure ample funding to cover all costs associated with achieving a bachelor’s degree at an in-state college or university for all foster youth who age out of the system and guarantee that former foster youth can afford tuition and housing at one of the state’s institutions of higher education.

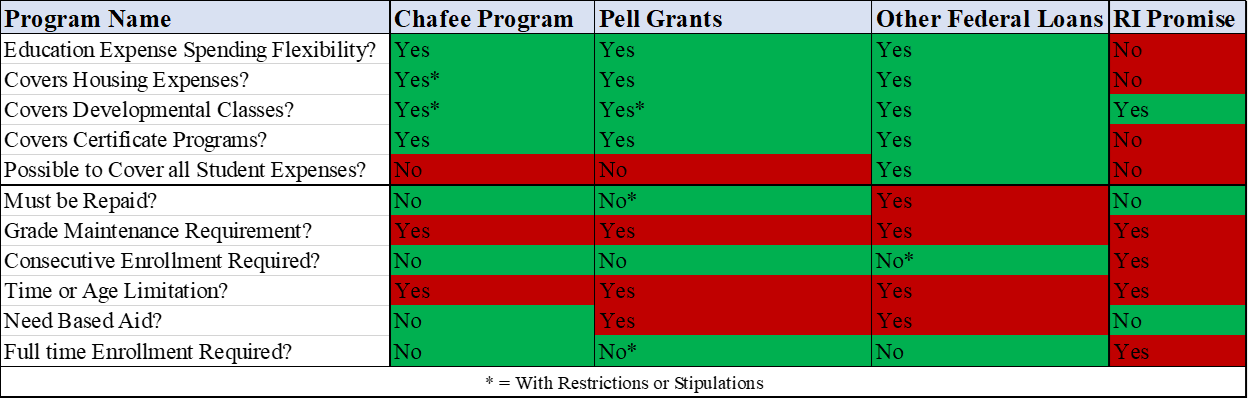

Recommendation 2: Eliminate or Ease Restrictions on Financial Supports Currently Available

If full funding for every foster youth cannot be achieved, there are alterations to the current funding available that could greatly expand the number of foster youths who access state resources to help them pursue their degrees. While it may at first appear that there are already a great number of funding opportunities made available to former foster youth, nearly all of the existing funding sources come with strict requirements and constraints which may make receiving funding difficult for foster youth. First and foremost is the Rhode Island Promise program, which allows for Rhode Island high school graduates who file the FAFSA[12] to attend the Community College of Rhode Island tuition-free. RI Promise only accounts for the cost of tuition and does not include books, transportation, housing, or other living expenses. Promise funding also only pays for the remaining amount of tuition left over after all other avenues of financial aid including Pell grants, Chafee Funding, scholarships, and institutional aid are exhausted.[13] RI Promise also requires that the student be enrolled in CCRI directly out of high school, locking out foster youth who may need time between high school and college to establish a stable living situation and employment to cover living expenses. Even if a foster youth applied for and was granted Promise, funding is dependent on a consistent 2.5 GPA and minimum 12 credit per semester course load requirement. Foster youth who must provide for themselves by working part or full time through college have been shown to struggle with their coursework.[14] As a result, these requirements limit the ability of Promise to be a source of higher education funding for much of the foster youth population.

Chafee Foster Care Independence funding and The DCYF Higher Education Opportunity Grant also have several restrictions that can disadvantage foster youth. Both programs have age restrictions, which limit foster youth from accessing funds if they take time off between high school and college or have to complete their GED or work before going to college. [15] These regulations block former foster youth from starting or finishing their education later in their adult life if college is not an immediate option following the completion of high school. Both programs also establish minimum GPA and full-time credit requirements which makes funding dependent on maintaining what their institution views as good academic standing while also being enrolled in at least 12 credits a semester. Maintaining full-time status is particularly challenging to foster youth in particular as well as any student trying to pay for living expenses while going through school. Given the many requirements and barriers that are placed on access to funding, there are still a lot of financial gaps that need to be filled for foster youth. For these reasons, we recommend that restrictions on federal and state funding regarding age, GPA, and full-time status, and time off between high school and college, be eliminated or eased to better suit the needs of foster youth navigating the challenges of early adulthood independence.

Recommendation 3: Provide personal educational liaisons to all foster youth to help ensure they receive the support they need in high school that prepares them for higher education

In addition to financial hardship, foster youth face educational disruption, lack of knowledge of educational resources, and lack support to help navigate the higher education system. Many of these barriers begin in middle school. As a result, foster youth require guidance and support throughout their time in public school to ensure that they are on a seamless path to higher education and a quality and secure adulthood. Parents normally fill the role of advocate for their child’s educational rights and progress. However, with foster children, the state adopts the role of the child’s parent, therefore an educational liaison is needed to fill the created void.

To help alleviate these issues and close this void, personal educational liaisons should be assigned to foster youths at the very latest in middle school, to focus explicitly on ensuring that foster youths have the support they need to succeed in school and ensure a smooth transition through their educational careers. Educational liaisons help foster youth choose classes, access resources such as scholarships for college, ensure proper testing for in-school special education services, and ensure those services are provided to the child (e.g. IEP resources). Whether they change schools or need help filling out essential financial paperwork, such as the FAFSA and scholarship applications, providing foster youth with these support systems will also help make it clear that their education is a priority.

Recommendation 4: Ensure all Foster Youth fill out the FAFSA as part of their transition plan.

One of the largest barriers to accessing higher education for all low-income students is successfully filling out the Free Application for Student Aid (FAFSA). Filling out the FAFSA not only opens up federal aid guaranteed to foster youth but is also the key to accessing other financial programs and scholarships such as RI Promise and many university-run scholarships. Currently, every foster youth must have a transition plan prior to leaving foster care at age 18. These plans should include filling out the FAFSA and going over continued education options and funding.

Many students do not go to college because they believe they cannot afford to even when they actually can if they accessed government financial aid. However, many students do not know about the funding available. All of the funding for college available to foster youth in Rhode Island is linked to the FAFSA. Thus, if every foster youth filled out the FAFSA, more would be likely to attend because they would know of the available resources to help them succeed. Studies show that those who fail to fill out the FAFSA do so because of a variety of complex and often personal circumstances.[16] The college application and financing processes are complicated, and students often rely on family members and other trusted mentors for guidance. Research has shown that the number one factor which significantly raises FAFSA completion rates is one-on-one interaction with someone familiar with the process of applying for and receiving financial aid. Outreach programs targeting underserved school districts which included one-on-one FAFSA counseling have been found to have boost FAFSA completion rates from 17.9% to 49% in just three years.[17] A personal educational liaison or social worker is an ideal resource to assist students in filing the FAFSA as they would provide the one-on-one guidance that foster youth may lack from members of their family. Requiring foster youth to fill out the FAFSA as part of their transition plan, could not only increase FAFSA completion but also increase college attendance.

Recommendation 5: Invest in programs to support success in foster youth transition and graduation from post-secondary programs.

Despite all the challenges foster youth face to get to college, for the foster youth who do succeed in making it to college, the challenges do not disappear. Foster youth require social support while completing post-secondary programs in order to succeed because foster youth continue to face educational and social barriers during college. In a study conducted in 2005, 63% of foster youth surveyed said foster care did not prepare them for higher education.[18] According to data gathered by the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, of the 16% of RI foster youth who attended higher education following high school, just 6% go on to graduate with a credit-bearing certificate or degree. Retention is a major issue for foster youth in higher education. A major goal for the state of Rhode Island must be to provide programs and supports to aid foster youth in college while mitigating the effects of an improper transition from grade school to post-secondary education caused by a lack of proper support and guidance for youth in the foster care system.

Social support is necessary for success in everyday life but is especially critical for youth in college. A study conducted in 2009 found that 84% of foster youth who successfully reached post-secondary education reported that social support systems, such as student organizations and mentors, were critical to their success in college,[19] and data shows that “non-traditional” students often need support while in college to ensure they complete their degrees. Given that foster youth lack the traditional support systems[20] that most college students rely on, providing programs to aid foster youth would increase the likelihood that foster youth succeed in college.[21] To provide these social and educational support systems, the State of Rhode Island can invest in the state’s foster youth by implementing programs at state colleges to promote educational success and aid the retention of foster youth in post-secondary education and invest in wrap-around services that include socio-emotional support for students pursuing workforce training through non-college programs.

Currently, several models exist that the state could build on. The University of Rhode Island currently implements programs that support youths from disadvantaged backgrounds, but do not specifically serve the needs of foster youth: The Talent Development (TD) program and the Multicultural Overnight Program (MOP). The Talent Development program is designed to support youth during their college career through a community-based learning setting, counseling and support, financial aid and grants, a mandatory mentor and educational assistance, and financing of housing costs. The Talent Development program is aimed at disadvantaged students who show academic excellence in the State of Rhode Island. This program allows students to attend college in the summer months prior to their freshman year to gain college credit. Students who complete the summer portion of the program gain financial support and are allowed to attend college in the fall. Talent Development students who continue to show success in TD maintain their enrollment and financial support in the program throughout their academic careers. Students are provided with advisors who help students navigate the college arena by assisting with financial aid applications, enrolling in courses, and provide routine check-ups to ensure that students are succeeding. Students are housed on-campus with other students who identify with each other to create a community, which provides youth with social support and a sense of belonging. This program ensures that youth have the same resources as students who do not come from disadvantaged backgrounds. It provides a support framework where students can eventually achieve independence and long-term success.

The Multicultural Overnight Program gives disadvantaged students a taste of college. The MOP program is designed to host out-of-state students from disadvantaged and marginalized communities for a weekend. This program involves programming to educate students on the benefits of college life and shows disadvantaged students that college is a place for them to succeed.

Rhode Island should implement programs similar to TD and MOP that are foster youth specific to aid the success of foster youth in higher education that would reach each of the state’s higher educational institutions and bring the foster community together to have the support they need to succeed educationally.

In addition to implementing these two academic success programs, another program that has shown to be beneficial for foster youth’s educational outcomes, and should be re-implemented, is the First Star Academy program. This national program was formed at URI, and despite its state and national success, was discontinued due to a lack of funding. The First Star non-profit charity organization strives to improve the lives of foster youth by partnering with various governmental agencies, universities, and school districts to ensure that youth have the support needed to transition to higher education and adulthood successfully. First Star accomplishes this mission by hosting university and college-based preparatory programs for high school aged foster youth during the summer. The First Star program provides life skills and vocational training, college course credit, and adult support, all while providing students with a positive college experience. By providing educational support and training, the First Star program allows students to develop skills to finish high school, as well as attend and be successful in college. It provides foster youth with first-hand college experiences along with the challenges they may face, in order to prepare them to better combat these challenges. According to Firststar.gov, “while over 80 percent of foster youth want to attend college or university, the inadequacies of the foster care system deprive them of the support to transform those hopes into reality.” This is important to note because this shows that if provided with proper resources to combat the constraints foster youth are faced with, graduation rates can increase and educational success can be demonstrated among this population. With proper educational intervention programs and resources, foster youth can achieve educational success and better educational outcomes.

As stated above, the First Star program is extremely successful in the 15 states it is established in, including regional neighbors Connecticut and New York. According to Firststar.gov, “98% of First Star Academy scholars have graduated high school, and 89% have enrolled in higher education.” Due to the success and educational support this program provides, the state should re-establish the First Star Academy Program. By implementing this program Rhode Island will be equipping youth with the tools necessary to successfully transition into adulthood, and achieve better educational outcomes. And works to support all of the foster youth who want to attend college and finish high school, but simply need the extra support and resources to do so.

Recommendation 6: Encourage foster youth to pursue their higher education at four-year colleges and universities to maximize their chances of educational success.

To maximize the financial security of former foster youth, the State of Rhode Island should emphasize promoting attendance at four-year universities. Based on data from DataSpark, the Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training, and the Rhode Island Department of Children, Youth, & Families, of those foster youth that go to college, URI and RIC had fewer enrollees but better graduation outcomes than those who went to CCRI. The data found that only 8% of foster youth who went to college attended URI, however, 36% of the foster youths who graduated did so from URI. A similar disparity can be seen at RIC, where 14% of the State’s former foster youth graduated from RIC, although the school accounted for just 6% of the total foster youth attendees. Finally, CCRI was shown to have the highest rate of foster youth attendees (66%), but only 50% of foster youth graduates had received a degree from CCRI.[22] This data suggests that even though fewer foster youth attend four-year universities when they do, they have far better graduation rates. Furthermore, data has shown that a two-year associates degree has a limited job and financial payoff. While workers with an associate’s degree make an average of $7,000 more per year than those with just a high school degree, bachelor’s degree-holding workers make on average $26,000 more per year than high school graduates and $19,000 more per year than those with an associate’s degree.[23] While having an associate’s degree is more beneficial than just a high school diploma, to truly benefit economically from post-secondary education, community college graduates must transfer to a four-year institution to earn a bachelor’s degree.

Community colleges often lack the on-campus community, organizations, and programs that four-year universities provide. Four-year universities also provide housing, dining halls, and the medical and mental health resources that many foster youths depend on to be successful. Further, most four-year colleges, including RIC and URI, have invested significantly in programs to increase student retention and graduation which are beneficial to at-risk students. Foster youth are better positioned currently to graduate if they attend one of the state’s four-year institutions as a result of these student supports.

The majority of individuals enrolled in community college take longer than six years to gain a certificate or associate’s degree.[24] Coupled with low completion rates, and the barriers foster youth face on an everyday basis, the structure of community college makes degree or certificate attainment often more challenging for those lacking support. For youth from disadvantaged populations, timeliness is an important factor in the choice to obtain a higher education. For students who do succeed in community college and decide to transfer, loss of credits poses a real and serious threat for many students. The loss of credits only adds to the time to obtain a degree, and whereas most students already take 6 years to finish at community college, losing credits and adding on more time is a substantial constraint.

[1] Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training (2020). Educational and Employment Outcomes of Rhode Island Foster Youth. DataSpark. http://ridatahub.org/media/datamart_reports/20200807_OnePager.pdf

[2] Kushel, M. B., Yen, I. H., Gee, L., & Courtney, M. E. (2007). Homelessness and Health Care Access After Emancipation: Results From the Midwest Evaluation of Adult Functioning of Former Foster Youth. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 161(10), 986–993. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.161.10.986

[3] Hook, J. L., & Courtney, M. E. (2011). Employment outcomes of former foster youth as young adults: The importance of human, personal, and social capital. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(10), 1855–1865. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.05.004

[4] Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training (2020). Educational and Employment Outcomes of Rhode Island Foster Youth. DataSpark. http://ridatahub.org/media/datamart_reports/20200807_OnePager.pdf

[5] Stereotype Threat Definition. The Glossary of Education Reform. (2013, August 29). https://www.edglossary.org/stereotype-threat/.

[6] Guyll, M., Madon, S., Prieto, L., & Scherr, K. C. (2010). The potential roles of self‐fulfilling prophecies, stigma consciousness, and stereotype threat in linking Latino/a ethnicity and educational outcomes. Journal of Social Issues, 66(1), 113-130.

[7] Guyll, M., Madon, S., Prieto, L., & Scherr, K. C. (2010). The potential roles of self‐fulfilling prophecies, stigma consciousness, and stereotype threat in linking Latino/a ethnicity and educational outcomes. Journal of Social Issues, 66(1), 113-130.

[8] Boser, U., Wilhelm, M., & Hanna, R. (2014, October 6). The Power of the Pygmalion Effect. Center for American Progress. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED564606.pdf

[9] Merdinger, J. M., Hines, A. M., Lemon Osterling, K., & Wyatt, P. (2005). Pathways to college for former foster youth: Understanding factors that contribute to educational success. Child welfare, 84(6).

[10] The $200,000 figure was passed into law in 2003 and has not increased with inflation, meaning the expenditure is worth significantly less in 2021 than it was when passed in 2003.

* RIC did not make the cost of summer housing readily available, though they do provide summer housing for students who show need and are involved with the college either through summer work on campus or summer classes. In order to approximate the cost of summer housing, we found the proportional difference in the school-year housing cost between the two institutions (school year housing cost at RIC is .84 of cost at URI) and applied that same proportion to URI’s summer housing cost to approximate RIC’s summer housing cost.

[11] Approximation obtained from Diane Correia, Educational Services Coordinator for RI DCYF, via email correspondence Nov, 2020

[12] The Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA) is the form completed by current and prospective college students that is required to access financial aid from the federal government as well as various state and institutional streams of financing

[13] Community College of Rhode Island. Frequently Asked Questions about Rhode Island Promise. CCRI. https://www.ccri.edu/ripromise/faqs.html#cost.

[14] Merdinger, J. M., Hines, A. M., Lemon Osterling, K., & Wyatt, P. (2005). Pathways to college for former foster youth: Understanding factors that contribute to educational success. Child welfare, 84(6).

[15] The Education and Training Voucher Program (Chaffee) cuts off funding at age 26, even if the youth has not exceeded the $25,000 limit, and the DCYF Higher Education Opportunity Grant limits funding to the age of 21, unless the youth is in good academic standing at their institution and already receiving DCYF funding, in which case funding may be extended until the academic year they turn 23.

[16] Davidson, J. C. (2013). Increasing FAFSA Completion Rates: Research, Policies and Practices. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 43(1), 4.

[17] Davidson, J. C. (2013). Increasing FAFSA Completion Rates: Research, Policies and Practices. Journal of Student Financial Aid, 43(1), 4.

[18] Merdinger, J. M., Hines, A. M., Lemon Osterling, K., & Wyatt, P. (2005). Pathways to college for former foster youth: Understanding factors that contribute to educational success. Child welfare, 84(6).

[19] Hass, M., & Graydon, K. (2009). Sources of resiliency among successful foster youth. Children and youth services review, 31(4), 457-463.

[20] Day, A., Dworsky, A., Fogarty, K., & Damashek, A. (2011). An examination of post-secondary retention and graduation among foster care youth enrolled in a four-year university. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(11), 2335-2341.

[21] Hass, M., & Graydon, K. (2009). Sources of resiliency among successful foster youth. Children and youth services review, 31(4), 457-463.

[22] Rhode Island Department of Labor and Training (2020). Educational and Employment Outcomes of Rhode Island Foster Youth. DataSpark. http://ridatahub.org/media/datamart_reports/20200807_OnePager.pdf

[23] Stobierski, T. (2020, December 14). Average Salary by Education Level: Value of a College Degree. Bachelor’s Degree Completion. Northeastern University. https://www.northeastern.edu/bachelors-completion/news/average-salary-by-education-level/#:~:text=Earning%20an%20associate%20degree%20brings,increase%20of%20more%20than%20%2426%2C000.

[24] Levesque, E. M. (2018, October 22). Improving Community College Completion Rates by Addressing Structural and Motivational Barriers. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/community-college-completion-rates-structural-and-motivational-barriers/#footnote-18.