After the Groundhog Day celebrations and prognostications have past, mid-February is about the time news reporters start asking tick experts “How bad are ticks going to be this year?” And after the “what winter?” most of us have experienced across the eastern United States so far in 2023, speculation will likely be even more intense, with the assumption being that since [lack of] winter didn’t kill ticks off, ticks are likely to be bad this upcoming spring and summer. Right?

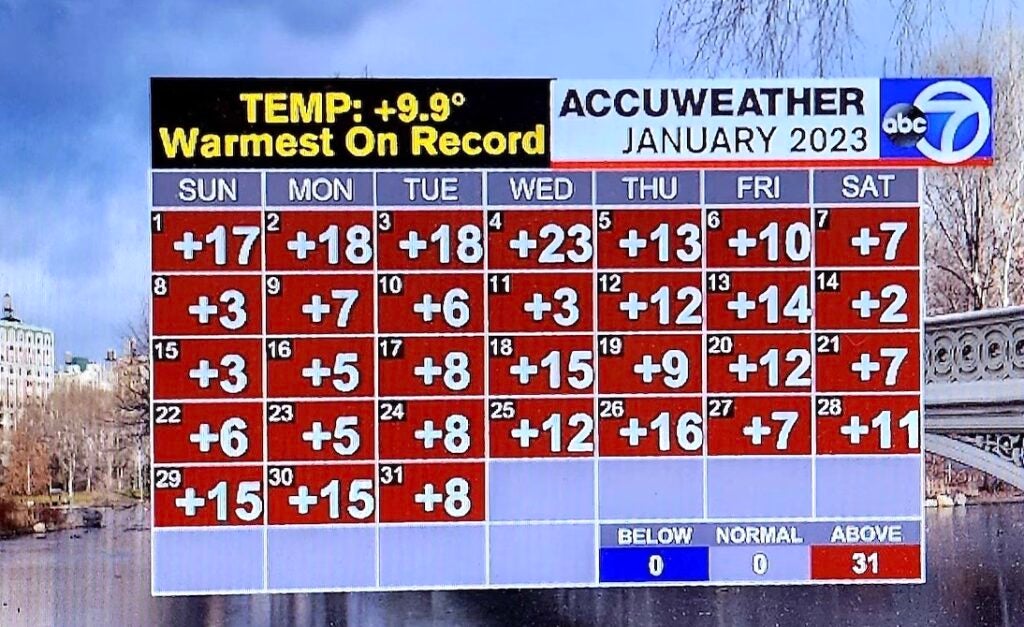

From Georgia to New England, most locations experienced one of the five warmest Januarys EVER. Warmest-ever daily records have been set. Boston’s winter has felt like Washington DC, and Washington like Atlanta. Accuweather reported that every day in January was above average temperatures in New York. Except for an 18 hr cold snap, February so far, also has been balmy. And yes, ticks ARE out and active; more specifically, adult blacklegged ticks, carriers of the Lyme disease germ are biting people and pets.

So, what do tick experts say about it? Is this weird, warm winter heading us all for a springtime and summer tickapocalypse? “No one can say right now,” agreed a recent consensus of seasoned tick scientists affiliated with the New England Center of Excellence for Vector-borne Disease (NEWVEC). Ticks have been around a long time and have figured out how to effectively survive winter. Adult stage blacklegged ticks, left over from their Fall active season, become active even in winter whenever temperatures are warm enough for them to move the muscles in their legs—usually above freezing. They’ve been active this winter quite a bit and their springtime activity usually peaks in April but could come a little earlier this year.

Then, there’s the poppyseed-sized nymphs, which typically start their springtime blood-quest in May, and one 10-year study1 showed how they start off at about the same abundance level each year, with the severity of their onslaught, and risk for Lyme disease, depending on weather patterns in early June, and not winter weather at all.

Scientists found it was the number and severity of drying conditions—they called them Tick Averse Moisture Events (TAMEs)—that was predictive of whether it would be a bad year for these ticks or not.1 TAMEs were any day when sub-82% relative humidity in the shady, leaf-covered habitat typical for this tick stage lasted longer than 8 hours. That’s when nymph ticks started to dry out–the proper term is desiccate—and die. Over the 10 year study, when June had more than 4 or 5 such TAMEs, then tick and disease risk was lower, usually about 50% lower.

The bottom line, ticks don’t die in winter, and the severity or mildness of winter weather doesn’t appear to predict spring and summer tick risk, but for blacklegged ticks, desiccating conditions in June definitely does. Still, it’s never too late (or early) to be ready for ticks. Make plans now—check our TickSmart actions for the best ways to protect yourself, your yard, and your pets against ticks.

1 Berger KA, HS Ginsberg, KD Dugas, LH Hamel, TN Mather. 2014. Parasites & Vectors 7:181-88.