“If it’s this hot now, imagine what hell must feel like!” I remember hearing this line growing up in the hot Georgia summer sun, one that always made me laugh but also reflect on how unbearably hot the outdoors felt. Moving to Providence as an adult, I thought that Rhode Island summers would be less sweltering, but given the immense asphalt and concrete around my neighborhood, and the lack of thick, lush tree canopy overhead to provide shade, summers here feel just as hot if not hotter than the ones I experienced growing up. However, there is a noticeable change being seen in Providence, as well as in other areas around New England and across the country.

It’s not simply that summers are getting hotter. There is a critical factor adding to the immense heat and increasing number of heat wave advisories striking cities. The distinct lack of adequate shade from trees, paired with the spread of asphalt as cities grow ever more urbanized, creates a deadly combination for many residents. Known as the “urban heat island effect,” the term refers to the compounded effect of paved surfaces in predominantly urban areas absorbing heat from the sun and further amplifying the average ambient temperature.

I first learned about the concept of urban heat islands when conducting research for my undergraduate senior thesis at Brown University on the history of residential segregation and environmental health disparities in Providence. One of the environmental factors that highlighted profound differences in the health of a community was tree canopy across a neighborhood. Those that had a lower proportion of tree coverage and greater proportion of paved surfaces (i.e., asphalt, concrete) faced higher ambient temperatures than those with more tree coverage. Trees are often taken for granted in our highly urbanized societies, but they provide immense benefits beyond merely providing the oxygen we breathe or adding aesthetic value to a neighborhood. They are especially vital to urban areas as they provide not only ample shade, but help lower overall ambient temperatures in an area.“There are a lot of benefits to having trees,” says Hayden McDermott, M.E.S.M. ‘22, Assistant Planner with the City of Newport, when asked about the importance of trees and tree canopy coverage. “There are mental health benefits: they encourage people to get outside, cool the area, including cars and houses, help to reduce utility costs, help cool urban microclimates, mitigate pollutants and flooding, and just make cities a better place to live.”

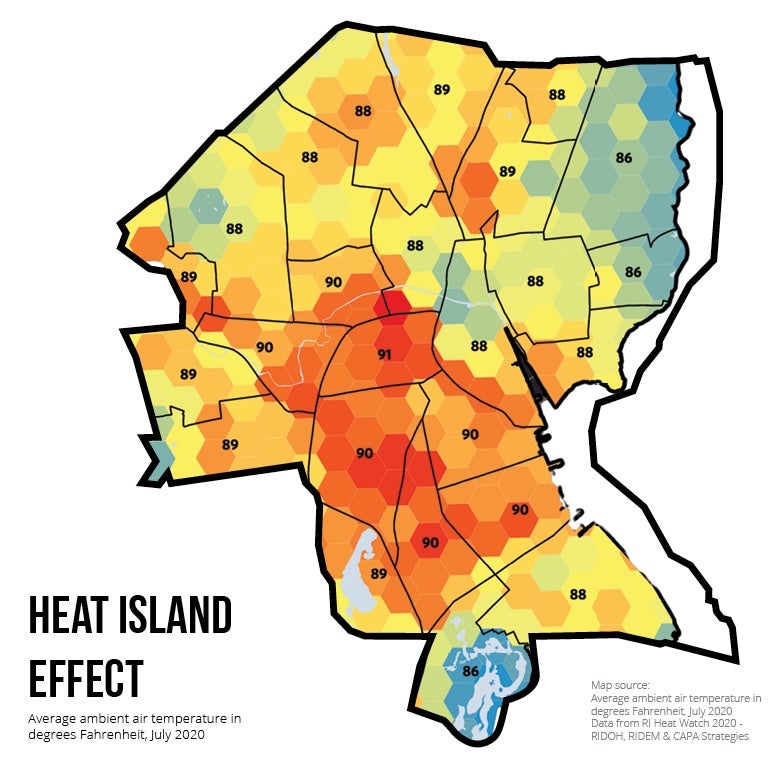

Particularly, the benefit of helping cool homes and reduce ambient temperatures within urban microclimates is something especially important in Rhode Island cities like Providence, Newport, and other areas, as rising temperatures are making summers more and more deadly in New England. These high temperatures, paired with highly urbanized areas that have mostly impervious landcover (i.e., surfaces that cannot absorb rainfall and made of artificial materials like asphalt or concrete) such as roads, parking lots, and driveways, create an environment in which heat from the sun gets trapped, resulting in higher ambient temperatures compared to areas with much less impervious cover.

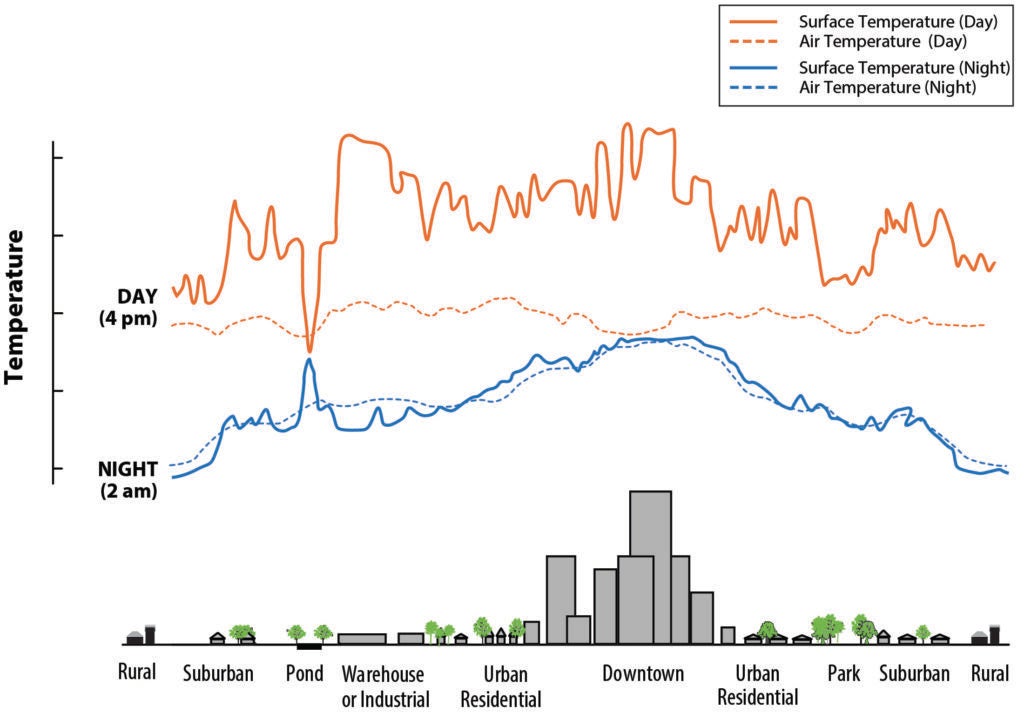

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency details this interaction on its website, noting that “structures such as buildings, roads, and other infrastructure absorb and re-emit the sun’s heat more than natural landscapes such as forests and water bodies” (EPA, ‘Learn About Heat Island Effects’).” Because of the stark difference in manmade structures like buildings and roads, most often and abundantly found within sprawling city centers and heavily developed urban neighborhoods, both absorbing and re-emitting the sun’s heat, these spaces then become “‘islands’ of higher temperatures” compared to surrounding areas like rural areas, or areas with more of its natural landscape remaining intact. These heat islands are no small, insignificant feat, as temperature differences can range from 1-7ºF. Both daytime and nighttime temperatures for urban areas tend to be 1-7ºF and 2-5ºF higher, respectively, than surrounding neighborhoods (EPA).

What is especially important to note is this increased range in outside temperatures in urban areas. According to the National Weather Service, a Heat Advisory is issued when daytime temperatures are 95°F-99°F over two consecutive days, or 100°F-104°F over a day; and an Extreme Heat Advisory is issued when daytime temperatures exceed 105ºF (National Weather Service, ‘Heat Safety’). A difference of a mere 1-6 ºF separates a heat advisory from an extreme heat warning, so areas that are facing elevated temperatures due to heavily paved surfaces absorbing and reflecting the summer heat are highly vulnerable to the impacts of such extreme heat conditions. Heat, in combination with humidity for areas like New England, can cause a range of ailments, such as sunstroke, heat cramps, exhaustion, dehydration, heat stroke, or even death. Heat advisories are a matter to take seriously, and though summers in Rhode Island may be short, they can still bring deadly heat waves. More than 2,300 people died nationwide from excessive heat in 2023, and a Rhode Island heat wave in 2024 with temperatures in the 90s led to a sharp increase in heat-related emergency room visits.

At least two heat advisories were issued for Rhode Island this summer, with temperatures exceeding 95ºF, and heat index values reaching 100ºF. It is also important to note that while other parts of the country have experienced much higher temperatures, the heat advisories reflect a deviation from the norm for a typical New England summer. Additionally, the added factor of the Ocean State’s humidity can make a 95ºF temperature feel more like 100ºF or more, posing a severe heat risk, especially to those living in areas without respite from the heat via tree shade or indoor cooling. According to NOAA’s National Centers for Environmental Information, “Rhode Island saw its second-warmest June on record and its warmest for nighttime minimum temperatures, which were 5.8°F above average” (NCEI, June 2025). Such temperature increases, paired with sustained high temperatures in summer, is not only an unpleasant experience combating the heat, but it also poses a severe health threat to those who are vulnerable to heat-related morbidity and mortality (Tong et al., 2021).

Providence is a strong example of a heat island and the impact that such environments can have on the temperature of an area. In a 2010 study conducted by researchers looking at development patterns and heat islands across 42 northeastern U.S. cities, they found that Providence not only had a highly dense development pattern (denser than Buffalo, NY, a city of similar size and environment), but also a greater heat island effect. About 83 percent of the city is densely developed, with surface temperatures found to be over 20ºF warmer than areas surrounding the city, nearly two times warmer than temperatures in Buffalo compared to surrounding areas (Voiland, 2010).

But why are urban heat islands and trees something so important for people to be aware of? This is just one piece of the larger puzzle of how individuals and communities fit into their local ecosystems. There is a delicate balance upheld within our environmental spaces, and with disruptive human activity such as urban development, these delicate ecosystems are being destroyed, stripping areas of the vast ecological benefits that were once provided, one such crucial benefit being the ability of trees in large numbers to help lower the ambient temperature within dense urban centers. “When you change the landscape, you’re changing the energy balance of the earth’s surface, and there are real consequences,” says University of Rhode Island President Marc Parlange. Having studied the environmental effects of trees on the atmospheric boundary layer – the lower part of the atmosphere where air movement across the earth’s surface occurs – President Parlange shared some of the additional benefits that trees and natural vegetation across a landscape can provide. “Trees provide friction and slow down the wind in the street, helping to reduce the pressure on buildings caused by the wind,” he says, “Under the tree, it provides cooling: not just shade, but it also creates stable boundary air, where the ground is cooler than the air.”

Though highly urbanized areas contribute to the urban heat island effect, both municipal planners and communities can combat the impacts of urban heat islands with careful planning and emphasis on nature-based solutions. Nature-based solutions are actions that help to protect, restore, conserve, and sustainably manage ecosystems, while also addressing societal challenges, thus helping both people and nature. Program director of landscape architecture and URI associate teaching professor Jane Buxton lists some of the ways that cities can tackle this challenge. “Municipalities can combat the urban heat island effect by increasing vegetation and reducing the dominance of heat-absorbing surfaces,” she says. “Nature-based solutions include planting and maintaining street trees, expanding urban forests, creating parks, and encouraging green roofs and green walls that provide shade and cooling.” Combating urban heat islands is an effort that has also seen collaborative and creative solutions by not only municipal planners, but individuals and neighborhoods as well. Buxton adds that communities can reduce heat by using reflective roofing and paving materials, planting trees throughout a neighborhood, or initiating garden programs, the latter two which provide shade and add green space to a neighborhood. “These community-based efforts show how residents can act locally while supporting broader municipal strategies,” she says.

Climate change is becoming an increasingly urgent concern that impacts our world not just on a large scale, but on smaller levels down to the microclimates that make up our neighborhoods and local environments. As temperatures increase and urbanization continues, it is imperative that city planners and other stakeholders consider more effective, nature-based solutions that can help combat the environmental changes that are inevitably going to impact where we live, work, and play. Moreover, individuals and communities have the opportunity to take action within their own neighborhoods by initiating programs that use reflective building materials, plant trees, or create green spaces. We cannot undo the vast urban development that shapes our cities, but we can seek out solutions that preserve or restore the remaining natural landscape, while improving conditions within urban neighborhoods and fostering eco-friendly collaborations.

Yvonne Wingard is a graduate student at the University of Rhode Island in the Master of Environmental Science and Management (MESM) Program, specializing in the Conservation Biology track. They are also a College of the Environment and Life Sciences (CELS) Communications Fellow, writing stories that highlight research and scholarship among faculty and students within the College.