The secrets she tried to spare her American children came back to haunt Mai Donohue ’02 as her children left the nest. Then it all came flooding out: her father’s murder; her abusive teen marriage; the son she left behind.

By Pippa Jack

“We grew up learning in parables,” says Maeve Donohue.

Her mother, Mary Mai Donohue, a homemaker and later educator, a taker-in of lost and parentless children, a fantastic cook and a stalwart member of the Barrington, R.I., community, just talks that way. It’s a holdover from her childhood in Vietnam. “Spoiled kids are like fat little birds,” she would tell Maeve and her brothers and sisters. “They can’t take care of themselves when they fall out of the nest, and the cat gets them.”

The six Barrington siblings, all born within seven years of each other in the 1970s, all a striking mix of their tiny Vietnamese mother and their tall Irish Catholic father, Brian, flourished in the public schools in leafy, sleepy Barrington. The town had welcomed the interracial family after they’d been turned away by towns in Brian’s native Massachusetts. The kids—four girls, two boys, athletic and smart—got along fine with their mostly white schoolmates. Sure, their family was a little different—for one thing, they took in refugee teens from Vietnam for a year at a time, a cause the community rallied around, dropping off mattresses and clothes to their modest three-bedroom home, which would be stuffed to the rafters with well-regimented children. Their mother deployed her cooking skills like a weapon, offering then-exotic Vietnamese dishes like banh mi to community fundraisers, along with her pitch-perfect pizza and Portuguese sweet bread. In her accented English, despite her fifth-grade education, she kept them in line and kept their homework on track. When it started to challenge her, she studied for her GED at night, keeping pace with their education.

But there was so much she didn’t tell them.

How she didn’t go by Mary because it wasn’t her real name—it was the name on the paperwork she’d bought to escape Vietnam. How in the 1950s, when she was very young, her wealthy grandfather’s political ambitions and religious beliefs had attracted the enmity of the local Viet Minh who ran her small village, Thong An Ninh in central Vietnam, a place torn between north and south in the violent decades that spanned the French and American Vietnam Wars. How her grandfather, father and uncles had been taken from the house one night and executed. How her mother had struggled to raise her four children, selling off land to pay for their educations—funds that ran out for Mai at only 11, since her younger brother’s education took precedence. How she had rebelled against her repressive rural upbringing, how her desperate mother had married her off to an abusive man who left her for dead on the side of the road. How, still just a teenager, she fled with her baby son, Anh, and they starved on the streets of Saigon.

How she was the Bad Luck Girl.

Brian had decided from the start that those were Mai’s secrets, and he’d support her whenever she was ready to tell them. But Mai (her name’s pronounced “My,” although she’ll never correct you) had found it impossible to reconcile her two worlds. She wanted to protect her well-adjusted, successful American children—who attended colleges like Stanford, Smith and Brown and may never have been rich, but had never known arbitrary violence or wondered when they would next eat—from the bad luck that had followed her for so long. Mai’s mother told her that she had lingered in the womb and almost killed her in childbirth, that she had been “born into the world under a cloud of bad curses, a bad luck girl.” That name had been the parable of her early life. She wouldn’t let it follow her here.

But as the kids left for college, she felt herself being left behind. Things came to a head as her two eldest daughters, Maura and Maeve, drove cross-country to Seattle one summer, and Mai wondered if a boyfriend was secretly going to accompany them. “Before they left, we had a huge fight,” Mai recounts. At some point, Maura wondered aloud what Mai knew about having a hard life.

So it was that Mai found herself suddenly telling her whole life story, for the first time, to one of her children.

Maura, a professional dancer and choreographer, wrote her first signature dance out of that experience. It’s called When You’re Old Enough, and the first time Mai saw it, she wept. “I realized that in not telling my children, I’d lived a lie for many years,” Mai says. “Always the memory of my lost child was like a knife in my heart, but the lie didn’t make the pain any better.”

The family rallied. Maura was the first to reach out to Anh, who had moved to the United States and joined the Navy by then; he and his wife and children are part of all their lives now.

And Mai, in characteristic fashion, made some bold moves—three, in quick succession. She went back to Vietnam for the first time, visited her mother and saw her siblings, now reconciled from the political differences that had torn their family apart, like so many others in Vietnam. She started working in the Barrington School’s Alternate Learning Program, teaching cooking to troubled teens, a connection that meant yet more children would end up taking shelter with the Donohues for a week or a year.

And she went back to school.

“I used to take my brother’s homework and use it to practice letters and math with my fingertip in the dirt of our back yard, after my mother told me I couldn’t go to school any more,” Mai says. “I always wanted an education. And as my kids went to college, I realized I wanted to be able to use the language that they and my husband used, be in the same world as them.”

It took her seven years to earn her associate’s degree in general studies from the Community College of Rhode Island. Another five to get her bachelor’s in human studies from URI, cum laude.

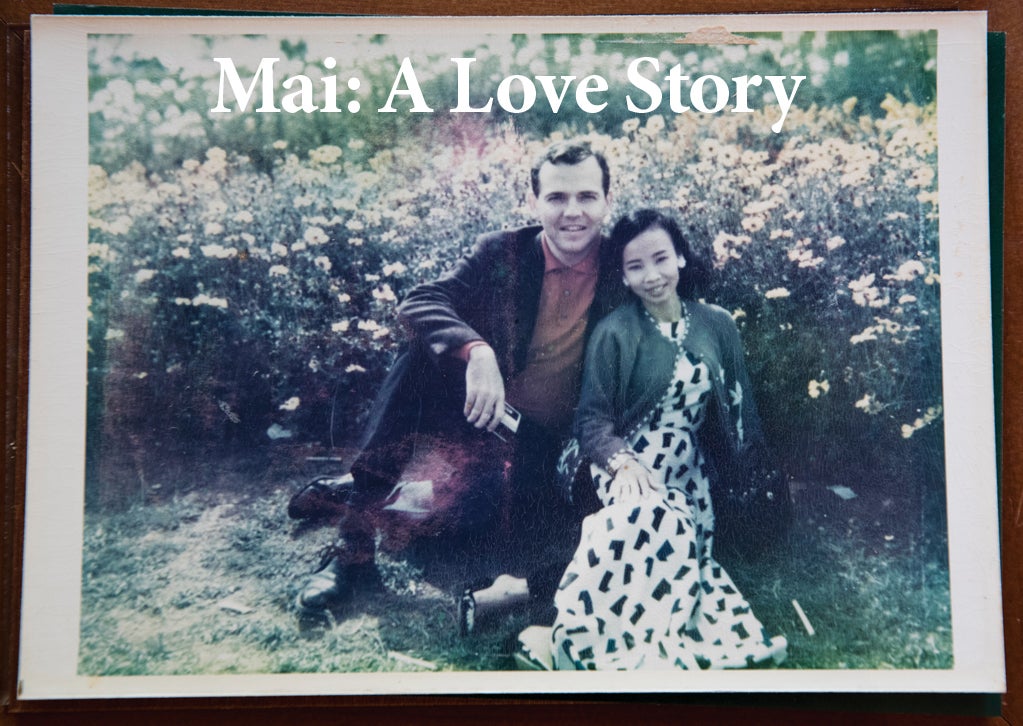

Those degrees each represent a story in their own right, and Mai is quick to say how grateful she is to both schools for helping her fulfill her life-long dream of a college education. But perhaps Brian put it best in a 2009 PBS documentary about his luminous wife, titled Mai: A Lesson In Courage, Passion, and Hope: “Mai’s graduations are triumphs,” he says, “triumphs of the spirit.”

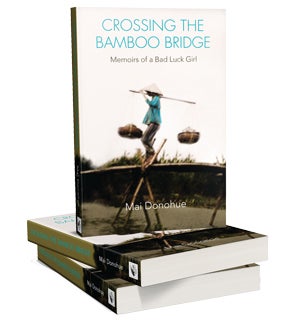

It was from Mai’s college experience that her book was born. It began as a class essay, and 25 years later, in September 2016, was printed by Stillwater River Press. It has so far sold close to 2,000 copies locally and on Amazon.

Crossing the Bamboo Bridge: Memoirs of a Bad Luck Girl chronicles Mai’s life up until she left Vietnam. It’s a way to come to terms with her younger self, the rebellious survivor who’s still a big part of Mai; and it’s a page-turner. There’s more there of Mai’s story: How she left baby Anh in her mother’s care while she tried to make a living in Saigon, where she ended up hiding out from the Viet Cong by nannying on an American base. How she began to teach herself English from the scraps of paper thrown away in the wastebasket of a bar she cleaned. How her abusive husband took Anh from her mother, and she despaired of ever seeing him again. How she figured out a method for working the wartime black market in dollars. How she met a tall Navy officer with the heart of a poet, who planned to be a priest, and told him her whole life story the day they met. How he would go on to give up everything, including his Naval commission, so they could be married.

“I always say Brian loves God, his country, and the Navy,” says Mai, “but he loves me more.”

She still cries when she talks about her early life, but she says that’s ok. There’s been a lot of healing, and there’s a lot more cohesiveness. Maura got married on the family farm in Vietnam, a place the Donohues, pitching in with their Vietnamese cousins, now help maintain. People live all over, but the warm months bring a constant parade of family back to Barrington’s Hampden Meadows neighborhood, where Mai’s grandkids remind their parents that her food is better than theirs.

She gives a lot of talks, after which audience members often come up to her to tell her how touched they are by her story, and how it inspires them to tell their own. And she’s planning more books. Sometimes she says the next one will be a memoir of her early years in the U.S.—the racism she and Brian encountered, the bewilderment she felt in U.S. supermarkets and during her first doctor’s visit, the time Brian was out of work one year and the electricity got shut off, but she made sure the houseful of kids never went hungry. How she and Anh found and forgave each other.

Other times, she says the next book will be fiction, based on her experiences with the Vietnamese underworld. But she’s probably furthest along with her cookbook. The working title is, wonderfully, Mai Goodness (that’s also the name of her website).

One thing is sure: Whatever she sets her mind to, she’ll accomplish. This bad luck girl makes her own luck. •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus