It’s early afternoon, and Richard Fazzio is in the den of his Woonsocket three-decker visiting with one of his best friends, Tim Gray ’89. They catch up: How’s your health? Pretty good for an old man. Are you eating? Sort of. Any tomatoes this year? Hope so.

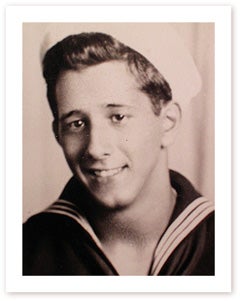

The two met years ago when Gray interviewed Fazzio for a documentary about veterans of World War II. Fazzio was a Navy coxswain who piloted a landing craft onto the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, the historic invasion of France that began the liberation of Nazi-occupied Europe. Gray still checks up on the 90-year-old at least once a month.

As it often does, the conversation turns to those seconds after Fazzio’s boat landed at Omaha Beach in the early morning hours of June 6, 1944. Fazzio begins: It was pitch-black. The sea roiled. German flak whistled by. Soldiers made the sign of the cross. The hull touched the sandy bottom, and the ramp went down.

Then Fazzio stops, lowers his head and weeps. He can’t go on. The images are too horrific. All 35 soldiers on his boat died, moments after they stormed the shore.

“It’s that one scene,’’ says Fazzio. “I can’t get it out of my mind. How do you talk about guys dying?’’

“It’s OK,’’ says Gray. “You’re allowed to cry after what you went through. No shame in that.’’

In the last decade, Gray has made 15 World War II documentaries about the men and women who risked their lives for freedom. Preserving their memories and recognizing their sacrifice is his life’s work. Along the way, he’s also become their friend.

Of the 16 million veterans who fought in the war, only 1.2 million are left, with 800 dying every day. Gray wants to reach the survivors before it’s too late, and he just might—through his nonprofit, The World War II Foundation, the only organization in the country that, with private contributions, makes films about the veterans and donates the movies to American Public Television and its PBS affiliates.

“I want to get to all the surviving World War II veterans before they’re gone,’’ says Gray, 48, of South Kingstown. “There’s a short window left. Each of these films is a gut-wrenching struggle to raise money for. Getting donations to make the films is the tough part. That’s what keeps me up at night.’’

The war has been his passion since he picked up a World War II encyclopedia as a kid. On his 10th birthday, he had one request: cassettes of Edward R. Murrow’s broadcasts from the German blitz of London. “The stories were about courage and sacrifice, good versus evil. I was hooked.’’ After cutting his teeth in sports reporting at the University of Rhode Island, where he studied journalism, he went on to a successful career as a sports anchor, ending up in his dream job at Channel 10 in Providence.

But his fascination with the war never wavered. In 2004, he decided it was time for a change. He left sports and took a leap into filmmaking, teaming up with seasoned photojournalist Jim Karpeichik. The first documentary, D-Day: The Price of Freedom, won two Emmys, and the duo was on its way. Today, the films are among the top five most requested programs by PBS affiliates nationally.

“This is the best thing I’ve ever done in my life,’’ says Gray. “We’re in the look-at-me, selfie generation. The World War II generation was taught to be humble and do its job without complaining. These guys saved the world, and didn’t ask anything in return. I want future generations to know about them.’’

Many do, thanks to Gray. Former Red Sox pitcher Curt Schilling, actor Tom Hanks, director Steven Spielberg, FedEx Chairman Fred Smith and Patriots coach Bill Belichick, whose father fought in World War II, are among the contributors. Gray even sends his films to Belichick to be screened before donating them to PBS. The actor Dan Aykroyd narrated one of the films, and filmmaker Ken Burns sent Gray a note praising his work.

What distinguishes Gray is his respect and compassion for the veterans. He takes them back to their former battlefields, in Europe and the Pacific, interviewing them while they walk the Normandy beaches or sit in an old French church with pews still stained with soldiers’ blood. The trips are both painful and uplifting—and always heart wrenching.

Fazzio had to be coaxed to return. After the war, he never talked about his experience, even though he was wounded and the recipient of a Purple Heart. Returning to Normandy, he says, “cleared his mind.’’ French schoolchildren hugged and kissed him. He signed his name on the bar at Le Roosevelt, a restaurant that hosts visiting veterans; and he walked the beach where he saw men barely out of high school get their faces blown off more than 70 years ago.

“Wasn’t the beach beautiful that day, Tim,’’ says Fazzio.

“Yes Richard,’’ says Gray. “It was.’’

Gray took Donald McCarthy, of Warwick, back too. McCarthy was a 20-year-old soldier in the 29th Infantry Division on D-Day and almost drowned when his craft tipped over. Clinging to a dead soldier floating in the blood-red water, McCarthy managed to swim to shore, but his joy at being alive was short-lived. German gunners hiding in the bluffs opened fire. Men fell around him. McCarthy froze in fear, then heard the call of his commander: “29, forward! Get off the beach!” Dodging bullets, he crawled for hours on his belly to a hilltop church, where he prayed with the rosary beads in his pocket.

He’s 91 now and walks with a cane. He still has the helmet he wore in battle, and touches it every day, his lucky charm. At Normandy last year, with Gray by his side, McCarthy stood in the exact spot where he landed years ago and watched a golden sun rise above the English Channel. This time, the sand was soft, and the water was calm, glistening. “I had to put my feet on the beach again,’’ he says. “One last time.’’•

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus