URI researchers determine how much hurricane-driven ocean currents modify surface waves and why it happens

February 9, 2026

Using advanced computer simulations, researchers from the URI GSO have concluded how and why strong ocean currents modify surface waves.

“Our primary finding is that hurricane-generated ocean currents can substantially reduce both the height and the dominant period of hurricane waves,” said Isaac Ginis, professor of oceanography. “The magnitude of wave reduction depends strongly on how accurately ocean currents are predicted. This highlights the importance of using fully coupled wave-ocean models when forecasting hurricane waves.”

Ginis conducted the research with GSO Professor Tetsu Hara and Angelos Papandreou, who earned his Ph.D. in oceanography from URI in December 2025. Their results were published in a peer-reviewed article in the Journal of Physical Oceanography in January 2026.

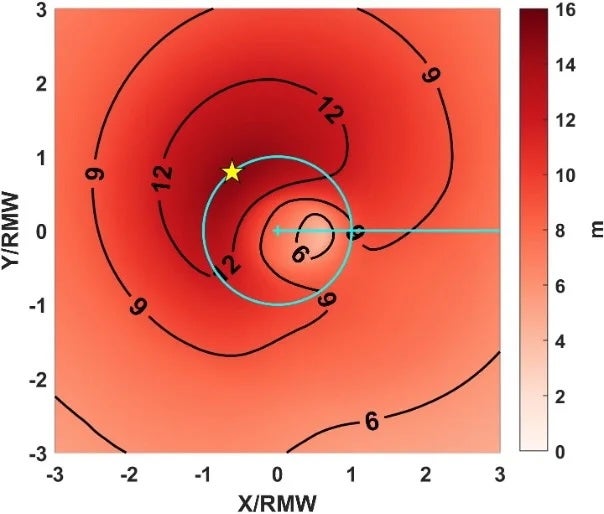

According to Ginis, waves are most strongly reduced by currents on the front right of the storm, where winds, waves and currents are typically strongest.

“On the front-right side of a hurricane, storm-driven currents move in the same direction as the waves,” said Ginis. “This causes the waves to travel more quickly through the high-wind region. Because the waves spend less time being energized by the wind, they do not grow as large as they otherwise would.”

The team’s computer simulations included hurricanes of different sizes, strengths, and forward speeds. Depending on the hurricane characteristics, the simulations revealed that the maximum significant wave height—the average height of the highest one-third of waves—can be reduced by 0.4-2.2 meters, or roughly 1-7 feet, and the dominant wave period can be shortened by about 0.3-1.5 seconds.

“While wave height often gets the most attention, wave period is also a key factor in determining how waves affect offshore or nearshore structures, such as oil platforms,” said Ginis.

The simulations required a powerful computer, so the researchers remotely accessed URI’s high-performance computing nodes installed at the Massachusetts Green High Performance Computing Center in Holyoke, Massachusetts. URI formed a partnership with the computing center in 2021.

Ginis is hopeful that the team’s research, which was funded by the National Oceanographic Partnership Program/Office of Naval Research, will be adopted by weather services to more accurately predict waves during hurricanes.

The professor will have an opportunity to discuss potential operational implementation of the team’s findings with NOAA scientists and hurricane forecasters at the American Meteorological Society Conference on Hurricanes and Tropical Meteorology in San Diego on March 30.

“This work has strong potential for operational use because we use the same wave and ocean models—WAVEWATCH III and MOM6—that are already part of the National Weather Service’s HAFS hurricane forecast system,” said Ginis. “Our findings could be incorporated without major changes to existing forecasting tools. Our group has a long history of working with NOAA scientists, and results from our previous studies have already been implemented in operational hurricane models.”