By Meredith Haas

Running between House Committee meetings across Capitol Hill may not be the future envisioned by most graduate students when they enroll in a science program. But GSO alums say the experience, and sometimes discomfort, may be one worth considering.

“You’re [hot from running between meetings] and trying to maintain composure in a blazer and fancy shoes you’ve probably never worn before. And you don’t know where you’re going because there are hundreds of offices in gigantic buildings you’ve never been in before,” says Basia Marcks, Ph. D. ’23, describing the flurry of her first weeks in Washington D.C. as a Sea Grant Knauss Fellow earlier this year. “There’s staff and lobbyists and activists. There’s a whole mix of all different kinds of people representing different interests around the country. Some are walking with a sense of importance and mission, and others are equally as confused as I am.”

“You’re [hot from running between meetings] and trying to maintain composure in a blazer and fancy shoes you’ve probably never worn before. And you don’t know where you’re going because there are hundreds of offices in gigantic buildings you’ve never been in before,” says Basia Marcks, Ph. D. ’23, describing the flurry of her first weeks in Washington D.C. as a Sea Grant Knauss Fellow earlier this year. “There’s staff and lobbyists and activists. There’s a whole mix of all different kinds of people representing different interests around the country. Some are walking with a sense of importance and mission, and others are equally as confused as I am.”

Marcks, who recently graduated with a Ph.D. in oceanography from GSO, pursued her degree intent on becoming a professor until she realized that teaching was just a small portion of the job. Compounded by drastic changes in the political landscape, she needed other options.

“We’re trying to find what the science says, do the research, get perspectives on what people’s concerns are, and make sure that there’s a lot of avenues for public comment and education around that.”Basia Marcks, Ph.D. ’23, Current Sea Grant Knauss Fellow

“Given the Trump presidency and how politics changed heavily while I was in [school], and how restrictive finding jobs in academia was … I didn’t want to be doing a postdoc in a state that maybe doesn’t respect things I find important in my life, or for my security, health or safety,” she explains. “But I realized I could use the same skills from teaching in different ways, and the Knauss Fellowship was a cool opportunity for potentially higher impact outcomes… to help inform better policy or people who are making decisions that will impact me and a lot of other people in our day-to-day lives.”

As a fellow, Marcks has been working in the Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife and Fisheries in the House Committee on Natural Resources, which is responsible for a wide array of nature resource issues from wildlife and fisheries to energy production and Indigenous affairs.

“They’re not really areas of bipartisanship, as you can imagine. Energy and mineral development, and species protections or water use have very different advocates on either end of the spectrum,” she says. “We’re trying to find what the science says, do the research, get perspectives on what people’s concerns are, and make sure that there’s a lot of avenues for public comment and education around that.”

The Sea Grant Knauss Fellowship is a unique educational and professional opportunity for eligible graduate students across the country, who spend one year in Washington D.C. working on marine and coastal policy issues in either a legislative or executive placement. Formed in 1979, the concept of the fellowship grew out of an era when widespread interest in the oceans was just beginning to emerge.

In the wake of World War II, the importance of understanding the oceans was apparent to the U.S. Navy, and the sea was becoming recognized as an important natural environment and resource. Expansion of economic activity in the coastal zone in the 1960s, along with a drive for U.S. competitiveness in science, and growing environmental awareness highlighted the need for national policy on issues like fisheries and coastal zone management.

In the wake of World War II, the importance of understanding the oceans was apparent to the U.S. Navy, and the sea was becoming recognized as an important natural environment and resource. Expansion of economic activity in the coastal zone in the 1960s, along with a drive for U.S. competitiveness in science, and growing environmental awareness highlighted the need for national policy on issues like fisheries and coastal zone management.

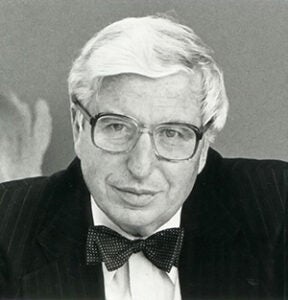

“Many of these issues concern the ocean and our need to better understand its role: changing sea-level, coastal pollution, modifying the earth’s climate, maintaining the current atmospheric chemical balance, and much more,” wrote the late Dr. John A. Knauss, namesake of the prestigious fellowship.

“Many of these issues concern the ocean and our need to better understand its role: changing sea-level, coastal pollution, modifying the earth’s climate, maintaining the current atmospheric chemical balance, and much more,” wrote the late Dr. John A. Knauss, namesake of the prestigious fellowship.

Knauss, a physical oceanographer and the founding dean of GSO, is an iconic figure within both oceanography and marine policy worlds as the co-founder of the National Sea Grant College Program, former Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere in the Department of Commerce, NOAA Administrator, president of the American Geophysical Union, and delegate to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

While the ocean has always seemed vast and untouchable, with roughly 80% still yet to be explored, our discoveries and continuing advances in technology emphasize the interconnectedness between humans and ocean processes and ecosystems. Knauss understood this and his legacy in ocean science, education and policy has transformed careers for thousands across the country over the last 43 years.

“I went to grad school planning on being a scientist and a professor,” says Whitley Saumweber, who earned his Ph.D. in oceanography from GSO in 2004. “Following the [Bush v. Gore] election, there was a lot of controversy with how science was being used or not used in policy, or was being edited… I remember a lot of us getting more fired up about that and interested in policy, and I had a few close friends do the Knauss Fellowship and was like, ‘Oh, that’s for me!’”

As a Knauss Fellow in 2005, Saumweber was placed in the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation that presides over matters concerning interstate commerce, science and technology policy and transportation. This experience, he says, helped to shape the trajectory of his career.

“My boss, [Margaret Spring], was the woman who wrote most of the important oceans legislation that came out of the early part of the century. Everything from Magnuson Stevens reauthorization, the Tsunami Warning Education Act, the first plastics law, harmful algal blooms legislation … all of this we worked on when I was there,” he says. “So I had this extraordinary experience being part of this process to create this incredible ocean legacy.”

Saumweber would go on to serve in various policy roles within the Senate and NOAA, which eventually led to serving as President Obama’s Associate Director for Ocean and Coastal Policy in the White House Council on Environmental Quality. “There was an article in The Atlantic saying how Barack Obama is the first ocean president and I take a huge amount of pride in that because they were talking about all the things that I [played a role in].”

As a clinical associate professor in the URI Department of Marine Affairs and a Senior Associate for Strategic and International Studies, where he serves as Director of the Stephenson Ocean Security Project, Saumweber says the Knauss Fellowship is a great opportunity for opening doors and maintaining connections.

Zoe Gentes, Knauss Fellow ‘16, echoes this sentiment but in light of a different career path. Gentes graduated from GSO in 2015 with a masters focused on geochemistry but knew she was drawn to communications.

“I was interested in communicating the importance of science to those who needed to hear it, which includes policymakers,” she says.

Placed in the U.S. House of Representatives member office of Sam Farr (D-Calif.), her experience within the appropriations committee provided invaluable insight into the voting process within the House and Senate. That experience also proved essential in pursuing a career in science communications. After her fellowship, she worked for various organizations from the Consortium for Ocean Leadership and the Ecological Society of America to her current role as a senior communications and marketing specialist for Battelle.

“I would not have gotten the jobs I’ve gotten without the Knauss fellowship … People know that if you have a fellowship like Knauss that you’re a hard worker. That you have what it takes to work in a fast-paced environment and produce the work. So it’s absolutely helped me.”

“If you look at the students from my generation, there’s a lot of (GSO alumni) with careers in management and policy.”Cynthia Suchman, Ph.D. ’98

Cynthia Suchman, Ph.D. ’98, (Knauss Fellow in 1999) also sought a different career path but in program management. She attributes her time at GSO and as a Knauss Fellow in helping direct the path to her current position as the Program Director for the National Science Foundation’s Biological Oceanography Program.

“I remember, as a grad student, Jim Yoder, M.S. ’74, Ph.D. ’79, former professor and associate dean at GSO, had just come back from a rotation at NASA and was talking about policy and management [when not a lot of people were] … He modeled a different way,” she says. “And if you look at the students from my generation, there’s a lot of us with careers in management and policy.”

Like Marcks, she too was placed in the House Committee of Natural Resources and gained insight into the inner workings of government by writing memos, floor statements and legislation, which required running to meetings with lobbyists and federal agency representatives.

“I think I lost 10 pounds that summer,” she laughs.

Both she and Saumbauwer did pursue their postdocs after their D.C. tenure, noting that serving as a Knauss Fellow doesn’t preclude one from going back to academia. Rather, it provides entry to the policy world and access to a network should you choose to pursue policy-making.

“It’s important to be open-minded to the opportunities as they come,” says Suchman, noting that one’s career is rarely linear. “The Knauss fellowship is the clearest pathway to make or explore the transition into policy. It’s not a final decision, but it does open a ton of doors … that shows you what another option beyond academia looks like.”