By Ellen Liberman

IN 1688, Pirate William Dampier marveled at the ingenuity of a Micronesian outrigger canoe: “One cannot stop talking about their great velocity, craftsmanship and lightness, because in the whole universe I do not believe there is a thing equal to them in nimbleness and swiftness,” he wrote.

Double-prowed, single-masted, with a shunting sail, this ancient design features an asymmetrical hull shaped by adze from a single log, to balance the outrigger float, lashed with coconut fibers. Every facet of the canoe works together to harness the wind, the waves and the weight of the mariners, propelling them to fishing grounds over thousands of square miles of open ocean. It is a tool of survival, but also of cultural cohesion—as a ceremonial object, a definer of gender roles, and an entree into adulthood. Today, even as technology supplants tradition, the canoe endures as a powerful metaphor for the geography of the atoll and of Micronesian society itself, with its complex networks of matrilineal clans exercising stewardship of their lands and waters.

Who’s to say that one part of this canoe is more important than the other?John Rulmal Jr., Co-Director, One People One Reef

“The main hull is designed to carry the weight, and the outrigger takes some beating but balances the main hull. At the same time, both move in parallel, fast. Who’s to say that one part of this canoe is more important than the other?” asks John Rulmal Jr., a community organizer from the islands of Ulithi. “A canoe cannot sail successfully without each of these crucial components.”

To Set a New Course

Within this interconnectedness of a people and their environment is an ongoing collaboration among scientists and the people of Ulithi to restore and maintain the coral reefs that underpin this atoll in the vastness of the Pacific.

Since 2015, GSO Associate Professor of Oceanography Kelton McMahon has been applying his expertise in stable isotope analysis to better understand the food web and its influence on the marine ecosystem in Ultihi, as a scientist for One People, One Reef. The organization was founded a dozen years ago to develop ways to work in concert with Micronesians on sustainable conservation practices. McMahon started as a post-doc at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and when he joined the GSO faculty in 2017, he brought URI into the project.

Ours is a model built on trust with the community and that takes a while to build.… When we miss collaboration, we miss information. We miss solutions.Kelton McMahon, Associate Professor, GSO

“This was born out of community concerns over the integrity of the coral reef, which is foundational to their food system, their culture, their social structure and their system of governance,” McMahon says. “We only formed this partnership through invitation; we reject the colonial, parachute science, where the Western scientist comes in and provides all the knowledge. Ours is a model built on trust with the community and that takes a while to build.”

“The Ulithians are equal partners—co-PIs on grants and papers. They are not people to be studied or to facilitate our research. They are the researchers with us,” McMahon continues. “The classic western approach—by far the most common—is very parasitic and extractive. It’s a disservice to the community, and it’s a disservice to the science. When we miss collaboration, we miss information. We miss solutions.”

Winds from the East

The Federated States of Micronesia is a chain of 607 islands hovering over the equator across 1,800 miles in the North Pacific, just east of the Philippines. Ulithi, one of the largest atolls in the Pacific, is ringed by 40 low-lying islands in the northwestern state of Yap. In the last year of World War II, Ulithi became home to the largest U.S. naval base, at its height hosting 20,000 troops and 722 ships. Admiral Chester Nimitz had recognized its strategic value as a staging area in the Pacific theater, and in one month, the lagoon was thrumming with aircraft carriers, destroyers, fleet oilers, and repair and fabrication ships. Seabees threw up an airstrip on Falalop, pontoon piers and a complete suite of recreation facilities for the sailors on Mogmog.

The U.S. largely abandoned its mini-city after the war, and many of the traditional ways returned to Ulithi, but Western influence and money continued to wash up on the islands in the form of reparations for wartime damage, grants and aid projects. Power boats were replacing canoes for those with enough resources to buy them and keep them fueled. In the 1980s, the Ulithian community in Hawaii introduced speargun fishing to Ulithi. These new technologies made it easier to fish, closer to home, but over time upset the reefs’ ecosystem and set fish stocks into decline. A weedy coral, Montipora, was taking over, the reefs recovered more slowly from storms, and erosion was increasing as traditional management practices degraded.

This confluence of factors, says Rulmal, began to eat at the islanders’ sense of agency, and, combined with the specter of climate change and sea level rise, a certain fatalism had crept in.

“All these things are beyond your control, so the result is: Eh, why matter? Let’s use it up. We’re going to go under anyway. I don’t have to worry about all this traditional management stuff because it’s obsolete.”

A Community Acts

In 2010, Ulithian leaders, impressed by the success of the community’s collaboration with the conservation non-profit The Oceanic Society on a sea turtle preservation project, reached out for help. Nicole Crane, then an Oceanic Society senior conservation scientist with experience in reef management in Belize and Honduras, recalls her first meeting on Falalop, one of the four inhabited islands of Ulithi.

“I met with men and we sat in a circle. They told me: ‘You are here to help. What should we do?’ I was caught off guard. I said ‘I don’t know what to do. This is your reef, your food, your community. But I’m willing to work with you to understand what is happening.’ And so we embarked on this journey.”

The effort acquired a formal organization—One People One Reef (OPOR), supported by grants and private philanthropy, and co-directed by Rulmal and Crane. The first task was to listen to community members to determine their needs; the second was to better understand the reef, using a combination of western and indigenous science and community input. One finding was that the practice of spearfishing at night was taking too many parrotfishes at key points in their reproductive cycle. A favorite food of Ulithians, this colorful herbivore was also a reef cleaner.

“[Parrotfish are] an important control on the growth of algae, and we were able to show the community data—how much algae parrotfish consume, and the data on algae cover versus the population of parrotfish, in a way that was visceral and compelling,” McMahon says.

What the Ulithians came up with was a more culturally relevant marine protected area.Nicole Crane, Co-Director, One People One Reef

Armed with this information, the Ulithian community developed its own plan. Western marine protected areas and fishing closures have earned a bad reputation in some parts of the world for failing to acknowledge local communities’ dependence on this resource for survival, says Crane.

“What the Ulithians came up with was a more culturally relevant marine protected area, one that involved rotating closures and allowed community fishing,” she says. “In less than a year, the biomass of fish doubled. It was an unbelievable response. Those reefs are really resilient.”

Passing on Knowledge

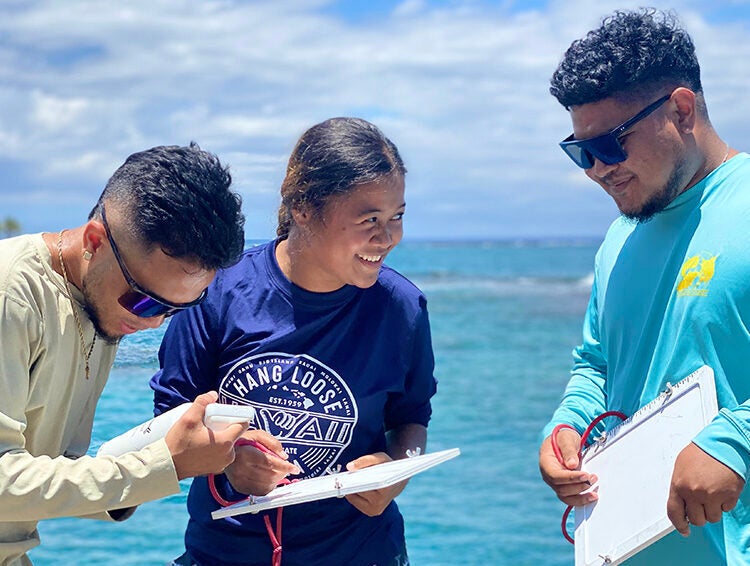

This summer, after a two-year COVID-enforced hiatus, OPOR’s Youth Action Program resumed on Kona, Hawaii, with a cultural and scientific exchange between American and Ulithian young adults. The GSO delegation included McMahon and Joshua Pi, a GSO Ph.D. student who conducted focus groups with Ulithian youth and elders to capture their views on spearfishing.

The program featured discussions and presentations on the application of indigenous and western science to marine conservation and marine management in Pacific Islands. It included a tour of the Hawaiian Marine Education and Research Center,

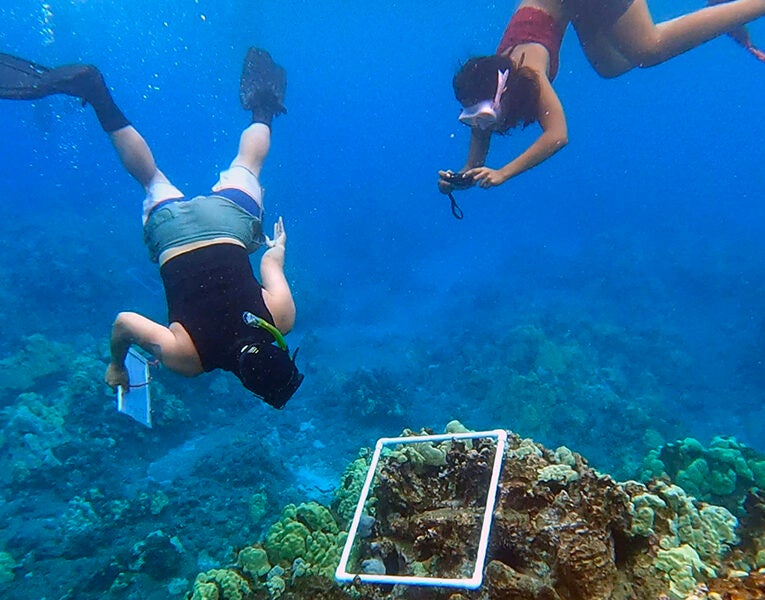

a meeting with the University of Hawaii Sea Grant, a one-day water monitoring project, and reef survey training in which participants learned how to conduct fish transects and benthic quadrat surveys.

In the second week, the students visited the Ulithian Wow Wow Park, operated by the Remathau (people of the ocean) Micronesian community on Kona, to learn native crafts, such as coconut husking and basket weaving. The exchange included a storytelling component, invigorating Ulithi’s ancient oral tradition by putting modern tools-—cell phones, GoPros and lavalier microphones—into young hands, to record interviews and songs related to reef management and the ecosystem.

Some of the biggest impacts of those two weeks seemed to lie beyond the confines of the scheduled activities. Pi described watching the boundaries between the U.S. and Ulithian students dissolve as they built connections that are ongoing today.

“There was a clear divide in the beginning between the U.S. and Micronesian students. But by the end of the two weeks, those lines were gone,” he says. “The discussions of culture and science united everyone. The research I’m doing is not possible without building those relationships where you want to understand one another. We still interact with each other on a biweekly Zoom call to get together, talk and hang out.”

Looking Ahead

Currently, Pi is organizing and analyzing the data from his focus groups for a future presentation to the Ulithian community. OPOR is mapping the reefs, with overlays of human use, to develop a tool kit local communities can use for reef diagnosis and management planning. URI is planning to go to Ulithi in January to resume data collection.

So far, this partnership has produced benefits beyond expectations.

The Ulithians have not only seen a significant increase in the fish biomass, but in hope for the future. Rulmal sees a change in attitude, with its young adults more engaged and ready to assume their responsibilities as the next generation to care for the reef.

“This initiative has proven with scientific evidence that it’s not all doomed and dead—we’ve turned these reefs around in less than a year.”

For the academic scientists, the result has been better science.

Everyone understands that neither spearguns nor power boats are going away. The centrality of the outrigger canoe in Micronesians’ daily lives may shift. But its message remains: every little piece of the whole has an important role to play; one is not more important than the other; together, we make progress.