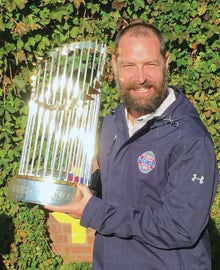

If ever there was a story about finding your own path, it belongs to Joshua Lifrak ’94. In his case, that path would lead to being part of the team that triumphed over the last great curse in U.S. sports. Here’s his take on career paths, Cubs culture, and what it’s like to approach the season after your big win.

By Pippa Jack

Josh Lifrak remembers sitting in class for his master’s in sports psychology at Ithaca College as the professor regarded his students doubtfully. “You know jobs are tough to find in this field, right?” he asked the class.

It wouldn’t have been so bad if Lifrak had been the same age as his classmates. But here’s how things had gone after Lifrak’s sociology degree at URI: some time traveling in Europe; an attempt to put down roots in Portland, Oregon; 10 years waiting tables in NYC.

There was no way that was the end-game, but finding the path forward, that was the struggle. How to reconcile the way he was with the things he was drawn to? Lifrak has always been interested in the life of the mind—his parents both held Ph.D.s in psychology from URI, so perhaps he never had much choice about that. But he is also a habitual, proud skeptic of conventional wisdom (his favorite memory from URI is of an adjunct lecturer, Russell Chabbot, who told him: “F*** the facts. Everything can be disproved sooner or later. Do your own analysis.”). He felt a deep yearning to make an impact somewhere in the world. And then there was his love of sports. He’d rowed crew at URI, gone on to mountain-bike and rock climb in those amorphous post-college years. He liked to push himself. And it was during one such bike ride, a really bad one, that he came to a central realization: His performance? It was all in his head.

“That’s when I knew I wanted to get back into sports,” he says. “But on the soft skills side.”

He didn’t have the right degree to get into a sports psychology program, so he took 20 credits at Brooklyn College, then applied to Ithaca. The whole time, he kept hearing the same thing: It’s nice you’re here, but employment rates stink. He was undeterred (those pesky facts). “One of the things I never took advantage of in Rhode Island was an internship,” Lifrak says. “At Ithaca, I knew I was going to have to get some real-world experience or no one was going to hire me. The college sports program at the Dill School always needed help, so I got a job there and immediately started devising my own mental skills program.”

He used the foundations of sports psychology: confidence, energy management, how you talk to yourself, focus and awareness. “You use your mind as a weapon to help you be successful,” he explains. The three biggest tools: affirmation, visualization, meditation.

Except, you couldn’t talk to the average college athlete about meditation back then. “Now, with all the research coming out, everyone is on board, everyone has a meditation app on their phone,” he says. “Many major sports franchises now have a yoga and breathing instructor embedded with the team. But back then, we had to steal a term from the military: tactical breathing. It sounded tough.”

The experience paid off at graduation, when he landed a job at the International Management Group (IMG) Academy in Florida. A specialized prep school and elite-athlete training center, it was one of the few workplaces for someone who wanted to do what Lifrak does. “You meet everyone at that place, they all just come through,” he says. “They paid me like I needed to pay them to work for them. They knew there weren’t many jobs. But it was a launching point.”

For nine years, he gave 15 to 20 lectures a week, for 37 weeks a year.

“It was like getting a Ph.D. in presentations,” he says. “But it was great because you had to come up with new stuff each week. You had to almost be an artist, and that’s something they talk about there a lot: the art and the science. A good practitioner has the scientific background to know what things to do, and the artistry to meld it all together and work through the cracks.”

In between lectures, “I would go work with a group of 15-year-old tennis players, then straight to an Olympic medalist, then to work with kids who were going to be in the NBA in two years. It’s a really unique and crazy place.”

The exposure helped him narrow his goals. There was something about working with baseball players. “The game sets itself up really well for mental skills development,” Lifrak says. “There’s the one-on-one competition in it, and the fact that the bat is round so the failure rate is really high. So there you are, and you’re having to deal with failure all the time, and the game stops and starts—not like hockey or something that’s fluid and keeps your mind from wandering. In baseball, something happens, then nothing, nothing, nothing. How do you train your mind to stay on it?”

So Lifrak felt he had something to offer the players. And, importantly, they tended to be open to it. “The guys are out there on the field, alone, and they come into the dugout and they immediately start talking because they’ve got so much going on in their head,” he says. “They tend not to have filters. And that’s great, because guys who are guarded are tough clients.”

When it was time to leave IMG, Lifrak started making calls—at least eight former coworkers were in professional baseball. He interviewed with the Cleveland Indians, and didn’t get the job. “Fit matters when you’re looking to join an institution, and I didn’t fit there,” he says. But the Indians admin liked him, and they knew something Lifrak didn’t: that the Chicago Cubs were hiring. “They called the Cubs on my behalf and said, ‘Listen, we found your guy,’” Lifrak recounts with wonder. “I walked into my office and there was a little light blinking and it was the Cubs calling me in for an interview.”

When Lifrak saw the young team assembled at his interview, it felt right. And then there was the century-plus Curse of the Billy Goat. It attracted him—he wanted to be there when they beat it. He wanted to see that fan base, unrivaled perhaps by any other except that of the Boston Red Sox, go wild, the city electrified.

It was August 2014, and the Cubs were in last place. Lifrak went straight onto Wrigley Field his first day and the game was sold out. “There was this energy to it,” he says. “I remember thinking the team was going to be really good in a year or two.”

Get In The Game

Whether getting ready for a weekend run or a sales presentation, Lifrak gives this quick tip for how to get in the right mindset:

“Get ready to be ready.”

Sounds simple, but “you have to get yourself grounded,” he says. “For a few days before, take a minute or two to meditate—there are hundreds of apps—and visualize what’s going to happen and how you’re going to handle it. See it happening, and tell yourself you’re confident, smart, professional. That way when you get to the event, you can stay in the moment.”

Lifrak says the phrase “Get ready to be ready,” by the way, is one he first learned from Cubs Hall of Famer second baseman Ryne Sandberg.

Maddon “just thought about everything a little differently,” Lifrak says. “The ingredients were there, and this chef came and mixed everything up and made a four-star meal.”

Manager Joe Maddon came on board the same season, and the next year, the Cubs won 95 games and went to the National League Championship Series. It had a lot to do with how Maddon “just thought about everything a little differently,” Lifrak says. “The ingredients were there, and this chef came and mixed everything up and made a four-star meal.”

Manager Joe Maddon came on board the same season, and the next year, the Cubs won 95 games and went to the National League Championship Series. It had a lot to do with how Maddon “just thought about everything a little differently,” Lifrak says. “The ingredients were there, and this chef came and mixed everything up and made a four-star meal.”

But there was a cloud. In the past, every time the organization had got close to success, something bad had happened. The curse made them feel they were up against the impossible. It almost had the weight of a fact.

Lifrak and his team set out to change all that: “When we came in, there wasn’t a true understanding of what it was to be a Cub. Sociology had trained me to look at people in groups, at the collective. From the minor leagues on up, we pushed the idea of culture.”

They co-opted the term ‘That’s Cub,’ which for decades had been far from a compliment. “We wanted to be great people first, and great baseball players second,” Lifrak says. “So every time someone did something above and beyond, even if it was a player picking up a discarded cup, we would say, ‘That’s Cub right there.’”

Cub itself became an acronym, standing for courage, urgency, and belief. “Courage to do the right thing, urgency to do it right now, and belief that you’re going to get it done.”

The team bought in. The next season, they won 103 games and then the World Series, breaking the 108-year curse. Some five million people showed up for the parade—the seventh largest gathering in human history. It was pure triumph.

In the aftermath, the organization hit some bumps. “We all got pulled in a lot of different directions,” Lifrak says. “I’m behind the scenes and even I felt it—speaking engagements, too much time away from family. I can’t imagine how the players felt.”

This season—Lifrak talked to us over the summer—the players were still finding their feet, and the slogan that had been their inside-baseball byword was suddenly everywhere. “Our marketing team used That’s Cub this year,” Lifrak says. But as far as the team goes, “I’m not hyper concerned,” Lifrak says. “We won our way. It was about togetherness, playing the game the right way, blue-collar hustling, everything that Chicago is about. We blew what was possible out of the water. If we trust our ability and work hard, more great things will happen.” •

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus