By Ellen Liberman

Earth awaits discovery.

Deep mysteries

To be revealed in time.

In 17 syllables, Margaret Leinen, Ph.D. ’80, stunned the room. In 2002, a consortium of scientists had gathered in Nagasaki to celebrate the launch of the Chikyu, the first Japanese ocean drill ship to join an international research effort to collect sediment samples from the deepest parts the planet. Leinen, as the head of the National Science Foundation’s geosciences directorate, had decided to commemorate the occasion with the spare elegance of a haiku. Leinen wove the name of the vessel and the program Chikyu Hakken (earth discovery) into the poem—and delivered it in Japanese.

James Yoder, then-NSF division director of ocean ociences and Leinen’s former URI Graduate School of Oceanography colleague, recalls a sea of dark business suits and an ambiance as formal as the milestone.

“It just blew them away that she would show up with a haiku related to ocean drilling. The looks on their faces,” Yoder says. “It was such a respectful thing to do, and to me, an example of how she would prepare for these things.”

After more than five decades of meticulous preparation in service to scientific scholarship, service and management, Margaret S. Leinen retired in May. She caps her distinguished career as director of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography at the University of California, San Diego, where she also served as vice chancellor for marine sciences and dean of the School of Marine Sciences. When she came to Scripps in 2013, she thought she would put in 10 years, but stayed to shepherd the school through a major expansion of its undergraduate program.

“I felt that I had to finish it up,” she says. “But I’ve been in university administration for 35 years. And I think it’s time for new blood. I look at the younger administrators around me, and I think they’ve got wonderful ideas.”

As an administrator, she also served as vice provost for marine and environmental initiatives and executive director of Florida Atlantic University’s Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institute, and as URI’s vice provost for marine and environmental programs, interim dean of the College of the Environment and Life Sciences, and the first woman dean of GSO.

Leinen has been a major force in shaping ocean policy in the U.S. and worldwide. She managed a $700 million budget as assistant director for geoscience at the National Science Foundation, served as a U.S. State Department ocean science envoy and co-chaired the U.N.’s Decade of Ocean Science advisory board. Leinen also led the Climate Response Fund and was chief science officer at a climate tech startup. Her leadership includes roles in major scientific organizations, board positions in ocean and science advocacy groups, and numerous honors, including election to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Leinen has been at the forefront of scientific, social, cultural, and institutional changes—from our understanding of the historical ocean, to gender shifts in science, and to major academic program transitions at some of the nation’s most prestigious oceanography schools. In the midst of these seismic developments, Leinen established a reputation as a thoughtful, unflappable, and analytical scientist, leader, colleague, and mentor.

“Whenever a problem or issue came that was controversial and complicated, Margaret was able to cut through the chaff, get to the critical part and develop good, sensible solutions with people,” says former GSO Dean Robert Duce, who tapped Leinen to be associate dean of research when he replaced Dean John Knauss in 1987. “I’ve never known anybody who has that ability as well as she does.”

Back in the Day

Leinen grew up in landlocked Joliet, Illinois. She had only seen the ocean once, from afar, when her family attended the 1963 World’s Fair in New York City. She entered the University of Illinois as a chemistry major taking classes in cavernous lecture halls, but fell in love with geology on a rainy November field trip to a strip mine.

“The faculty had brought a thermos of coffee for us. We’d be sitting on a rock with a faculty member drinking coffee. They talked to us like we were real people and I said, ‘Hey, this is what I want for science, not this crazy chemistry experience.’”

She was fascinated by the big earth processes of volcanoes and earthquakes, but eventually decided that her interests lay at the bottom of the ocean, where the sediment reveals the history of an ancient earth. In 1975, she earned a master’s degree in geological oceanography from Oregon State University.

“The idea that I could look at these sediments and say, ‘Here’s what the ocean looked like 30 million years ago’—I loved that.”

When Leinen began her studies, the ranks of women scientists were thin and women at sea were a novelty. As a chemistry undergraduate, she was one of only five females in classes of 400. The males had assigned seats, but the females were rotated to give the men experience in sitting next to a woman. Research ships lacked bathrooms for women, and the culture could be challenging. During one of her first cruises, Leinen and her fellow graduate student Kathryn Sullivan, the geologist, oceanographer, and former astronaut, were headed to the ship’s fantail to prepare the gear for dredging and coring, when the ship’s bosun stopped them at the lab’s threshold.

“He pushed us back to the doorway drew a line with chalk and said, ‘No women behind this line, because you could distract people and cause an accident.’”

Another set of cruises was to conclude ashore with a big party at a hotel. The ship captain’s wife asked Leinen and Sullivan if they had packed skirts.

“We looked at each other and said, ‘Yes, we have a skirt for the port stops.’ And she said, ‘Oh good, because we want you to serve the hors d’oeuvres at the party.’” (They didn’t.)

“Much later on, that bosun apologized,” Leinen says. “But sometimes things don’t change. In 2021, when I was selected to be the co-chair of the Decade Advisory Board, somebody told me that I was only selected because I was a woman.”

Leinen countered by striving for excellence.

“I made sure that all my grades and my research were the best,” she says. “The men were the darlings of the lab, so you kept your head down and tried to outperform them.”

Leinen spent half of her career at URI. When she arrived in 1975 to pursue her Ph.D., the graduate program was only a decade old. But the GSO campus was undergoing a rapid expansion in those years: the Marine Ecosystem Research Laboratory opened; the research vessel Endeavor arrived; and the Norman D. Watkins Laboratory, Corless Auditorium and Marine Resources Building were completed.

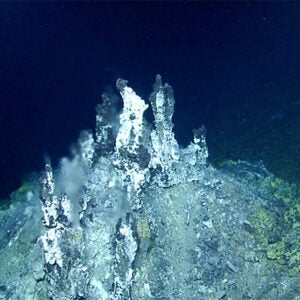

After earning her Ph.D. in 1980, Leinen began to support her research with grant money. It was a productive time; she published widely on paleoceanography, paleoclimatology, and biogeochemical cycles, carbon cycling, and their relationships to the climate history of the oceans. She accrued 24 research cruises. As a member of the Joint Global Ocean Flux program, she co-led seven in the equatorial Pacific. Her favorite was the Alvin dive to the Juan de Fuca spreading centers. She had been studying the sedimentary record of those hydrothermal vents since the 1970s. In 1984, she got the opportunity to descend 65-hundred feet in the submersible to observe and sample them.

“I had spent my entire life studying the ocean and now I was actually able to look into it, not just at the top of it, but into it,” she says “We were the first people to lay eyes on those vents. And it became clear that there was much more diversity of life around these deep-sea vents. It was amazing.”

Adept Leader in Academia

Meanwhile, Leinen ascended within GSO—from research staff to faculty member to associate dean of research. When Duce left to take a position at Texas A&M University in 1990, Leinen was selected after an international search. During her tenure as “Dean of the Deep,” GSO rose in the National Academy of Sciences rankings of oceanography programs to fifth in the nation, and increased its extramural funding by 50 percent. She expanded the size of the research faculty and developed partnerships with groups inside and outside of the university. For the first time, GSO developed a coastal management plan with the state and began collaborating with the Coastal Institute. She helped to develop GSO’s first undergraduate programs, a “blue master’s” program with the business school, and a master plan for marine and environmental programs university-wide.

Yoder says that integrating GSO into URI’s undergraduate programs showcased Leinen’s skills as problem solver.

“[President Robert L. Carothers] was pressuring GSO to transition from a research and graduate education institution to a standard faculty department. That caused tension in the faculty, and Margaret was trapped in the middle. But she was able to convince [Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs M. Beverly Swan] to adjust the accounting model to include federal grant support. That was one of the ways that she was successful in trying to keep GSO’s identity pretty much the way it was.”

Similarly, Leinen oversaw sweeping program, funding, and faculty changes at Scripps. Over her 13 years, she presided over a major diversity and equity initiative, the faculty increased by 33 percent, undergraduate enrollment nearly doubled, and new ocean, atmosphere and interdisciplinary environmental systems majors were created.

“We did it without changing the teaching requirement,” she says. “I had practice at URI.”

In addition, the Scripps endowment tripled, and the funding sources diversified among federal, state and private donors. Leinen forged stronger relationships with government officials “to really tell them what Scripps is doing for them and for their constituency—our work on sea level, algal blooms, wildfires, atmospheric rivers and the big weather patterns. We’re so proud of the institution. It’s exciting to tell people how much is going on and how impactful it is.”

Her longtime colleagues say that Leinen’s encyclopedia of accomplishments, is due, in part, to her extraordinary facility with people.

“She essentially helped to change the culture, and as we can see in the current political landscape, culture change is hard,” says Marine Chemistry and Geochemistry Professor and faculty equity advisor Lihini Aluwihare. “Her super-power is making people feel like they belong.”

Humanity in the Sciences

Duce marvels at the 25-year-old bottle of classic Macallan scotch Leinen intended to gift him as he took over the AGU’s presidency at the annual meeting in Paris. The bottle broke when the bag it was in fell off the security conveyor belt at the airport. Leinen scoured Paris for a replacement, but had to settle for another.

“You’d think I would be giving her a gift because her term was up. No, she was giving me a gift because my term was beginning.”

Richard Murray, Deputy Director at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who came to GSO to study with Leinen as a postdoctoral fellow recalls the moment that crystallized her value as mentor. The pair had submitted a proposal to the NSF, and “it just got blasted,” he recalled. “She said, ‘You get reviewed like this and you wonder why we even do this job.’ It’s one thing for a snot-nosed recent Ph.D. like me to get crappy reviews. But for an established scientist to articulate that in the presence of someone she’s supervising, it showed me that it’s okay to take a hit to the chin, pick up and move on.”

Her former NSF boss Rita Colwell praised Leinen’s ability to keep a firm grip on the science as she gained community trust during the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative to study the effects of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill.

“The first meeting had a big turn-out, and there was suspicion. They were facing contaminated fish, beaches washed with oil, and toxic fumes. Would these funds actually solve problems? Or was it going to be ethereal research?” she says. “As the work progressed, the community’s confidence was clear. Those town halls continued, but they were friendly.”

In retirement, Leinen will continue to administer her grants, to research and advocate for the ocean. More hiking and cooking international fare are also on the agenda. She’ll miss being among the first to hear about the next thrilling discovery.

“The faculty, the researchers, the postdocs and the graduate students—everybody wants you to know about their research because they’re very proud of it. There’s this constant stream of people telling you the most wonderful science and that hasn’t even been published yet.”

She leaves academia with a record of scientific advances, transformational leadership, successful mentees, and mementos—like the piece of NSF stationary with the haiku. Leinen knew she’d be required to toast the Chikyu and saw an opportunity to put her love of Japanese literature to good use. She enlisted her Japanese counterpart, Asahiko Taira, for help.

“I had done something in English, and he said, ‘Let’s turn it into Japanese.’ We translated my idea, but he made it so much better. He wrote it out in Japanese so that I could show the Japanese colleagues the haiku in Japanese. Then he phonetically wrote it, so I could say it in Japanese.”

Like so many Margaret Leinen stories, it’s about collaboration, humility, the element of surprise, and, she says “it was fun.”