By Michael Blanding

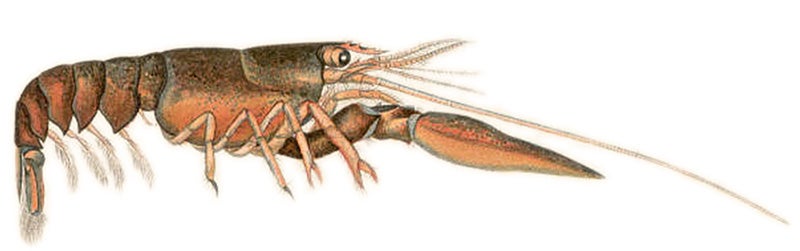

Lobster is a mainstay of many a Rhode Island shore dinner, as it is throughout New England. The local story of lobsters and their crab cousins in Narragansett Bay, however, has been one of constant ups and downs. During the 1960s, crustaceans were few and far between in the bay. Then climate change started warming the seawater, leading to the northern exodus of winter flounder and other bottom-dwelling fish that liked to munch on juvenile lobsters and crabs. The population exploded, reaching a peak in the 1990s.

“Some called it the crabification of Narragansett Bay,” says Professor of Oceanography Candace Oviatt, Ph.D. ’67. “Suddenly, we had a ton of crabs in the bay.” And where you have crabs, she says, you have lobsters. “They go together.” The boom was great news for the southern New England lobster fishery, opening up new territory for trapping. But just as suddenly as the lobsters came, they started to disappear, dwindling to almost zero today. The question is why? Was it the effect of the continued warming of the seawater impacting lobster survival? Was it new predators moving into the neighborhood? Or was it something else entirely?

New research by Oviatt and Kristin Huizenga, Ph.D. ’22, undertook several novel experiments to get to the murky bottom of the problem, publishing their findings in a new paper in Marine Ecology Progress Series, “Inshore juvenile lobsters threatened by warming waters and migratory fish predators in southern New England.” “We can think of the direct effects of temperature, like can their bodies handle these changes,” Huizenga explains—higher temperatures, for example, have been correlated with higher rates of epizootic shell disease. “But there are also indirect effects of temperature in the way it changes interactions with other species.”

In particular, Oviatt and Huizenga suspected the predatory influence of scup, a migratory schooling fish that has become more common in Narragansett Bay due to higher temperatures and more stringent fishing regulations, as well as black sea bass, which has recently extended its range northward. A third potential culprit are invasive Asian shore crabs, which might displace them from the cobble they like to hide in and might also eat lobster if given the chance. “It was exciting to be able to work on something with such a critical impact for lobster fisheries, which is such a major part of New England,” says Huizenga, who based her doctoral thesis on the research.

She and Oviatt began by placing juvenile lobsters inside individual containers in one of three temperature treatments inside the Ann Gall Durbin Aquarium. (If left to roam free inside, they could attack and kill one another—the reason for the rubber bands around their claws at the supermarket.) In one treatment they mimicked the ambient temperature of the bay, which ranges seasonally between 20 and 22 degrees Celsius (68 to 72 degrees Fahrenheit); in the other two, they tested temperatures three degrees cooler to imitate the bay’s previous temperature, and three degrees warmer to reflect the potential effect of continued warming.

It’s the younger stages of species that tend to suffer, and that ultimately determines the adult population.Professor Candace Oviatt

The researchers used juvenile lobsters, sourced from the Sound School of Aquaculture in New Haven, Conn., since they are both more susceptible to the impact of temperature and less able to flee warmer water—as well as being more apt to be eaten by fish. “It’s the younger stages of species that tend to suffer,” Oviatt says, “and that ultimately determines the adult population.” When they left the lobsters in the temperature treatments for 12 weeks, however, almost all of them survived the challenge, even those in the warmest tanks. In fact, of the more than 150 lobsters in the experiment, only three died, all in the coldest tank.

their experiments at the mesocosm facility.

“I was surprised,” Huizenga says. “I was expecting to see more deaths—especially in the three-degrees-warmer treatment.” On the other hand, the researchers did find that the lobsters in the warmest tank did not grow as large as those in the cooler tanks, despite offering them the same amount of food. Those lobsters also tended to be more lethargic, leading to less of an appetite, which could have affected growth. “Usually when you go to feed them, they bring their claws out and do a little dance,” Huizenga says. “But the ones in the hot treatments didn’t dance very much or ask for more food, showing signs of physiological stress.” While higher temperatures alone doesn’t seem to explain the decline of lobster in the bay, Huizenga and Oviatt speculate, they could lead to less healthy lobsters overall. “They don’t die from temperatures, but they do get weaker and don’t grow as quickly, which can make them more susceptible to the myriad predators moving into the bay.”

To better examine the impact of those predators, the researchers set up several mesocosms, meter-wide in-ground containers filled with seawater from the GSO’s coastline. Along the two-meter deep bottoms, they placed boxes full of juvenile lobsters with plenty of cobble substrate for them to hide in. They then placed predators in the water to see how they’d react. In the first set of experiments, they used nine mesocosms total, placing no scup, two scup or four scup into three mesocosms each. In a second set of experiments, they again set up nine mesocosms, leaving three mesocosms empty of predators, and placing two black sea bass or four Asian shore crabs in three each of the remaining environments.

The researchers dialed back the amount of food they gave the fish, to keep them a little hungry. “We didn’t want them to be too stuffed,” Huizenga says. “This way, they are incentivized to go after the food sources that are running around.” And go after them they did. In the scup experiments, it didn’t matter how many fish were in the mesocosm—they decimated the lobsters, eating an average of two-thirds of the lobsters in the environment. The black sea bass also seemed to enjoy lobster dinner; in those mesocosms, lobsters were twice as likely to die when the fish were present. Only the lobsters paired with the Asian shore crabs seemed protected from slaughter. They survived about as well as the lobsters without predators.

Oviatt and Huizenga speculate that Asian shore crabs may not have had enough of a chance to invade the cobble habitats inside the boxes, since the lobsters were placed inside several days before the crabs were introduced; or perhaps, lobster just isn’t to the crabs’ taste. As for the fish, both species seem likely to have contributed to the sharp decline of lobsters in Narragansett Bay. The researchers bolstered this finding by examining the guts of scup and black sea bass caught in the bay. In the majority of them, they discovered several species of crabs, including rock crabs and Jonah crabs, which inhabit the same territory as lobster, showing that the fish do indeed seem to be hunting in those areas.

In a surprisingly few of the fish bellies, they found remnants of lobster as well. “It could just be that we no longer have a strong lobster population here, so the fish are eating what they can get,” says Huizenga. In other words, the fish have already decimated the lobsters so much that there aren’t many left to eat. “The fish are very effective predators in cleaning up post-larval and juvenile lobsters,” Oviatt says. “I am amazed that there are lobsters left in the bay with that many fish predators around.”

In another set of experiments that have yet to be published, however, Huizenga points to yet another possibility for the dearth of lobsters: babies aren’t making their way into Narragansett Bay in the first place. Again, the phenomenon seems to stem from climate change, which has impacted currents in the Atlantic, shifting warmer waters influenced by the Gulf Stream up onto the continental shelf, and cutting off colder water from the Labrador Current. That could, in turn, lead lobsters to stay in the deeper water farther from shore, so their young don’t reach the bay.

Huizenga tested that theory with a number of net tows in the bay, as well as traps which catch lobster larvae and other plankton at night, so they can be counted in the morning. “I basically found that we are getting very few larvae in Narragansett Bay, so we wouldn’t get a lot of juvenile lobsters either,” she says. Records from the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, seem to corroborate this, showing a decline of adult lobsters first, followed by larvae, and then juveniles.

It could just be that we no longer have a strong lobster population here, so the fish are eating what they can get.Kristin Huizenga, Ph.D. ’22

The real story of the decline of the lobster population may be due to all of these factors working in tandem—including less lobsters making their way to the bay in the first place, and those that do become weaker and more likely to be eaten by predators. “Predation would trim down the population drastically, but it wouldn’t eliminate it,” Oviatt says. “But if there were no new lobsters coming in, that could be the final straw.

Ultimately, the combined pressures on the lobster population explain the decline, the researchers say, leaving questions of what with little that can be done to counteract the loss. “I think this boom we had in the 90s, when the lobster fishery was very strong, was kind of unique,” says Huizenga. “We could have climatic fluxes that could change things a little bit, but if we continue on this warming trajectory, this will be a very difficult habitat for lobsters.” That doesn’t mean that Rhode Islanders will have to forgo their lobster rolls or boiled lobster dinners. The fisheries in northern New England and Canada remain strong. But it does mean that when they bite into their buttery meal, it will be less and less likely to have come from Rhode Island.