By Betty-Jo Cugini and Peter Hanlon

In the summer of 2020, GSO Dean Bruce Corliss will take one final look out of his office window across a sweeping view of Narragansett Bay’s West Passage, and place an envelope on the top of his desk. Before he steps down from his position of eight years, GSO’s fifth dean will perhaps start a new tradition by leaving an encouraging note for the incoming sixth dean.

By any measure, Dean Corliss has had a major impact during his tenure. With a new research vessel set to arrive in 2023, a campus master plan with multiple construction projects in the works, and after bringing in numerous new faculty and staff, he leaves behind a school and campus poised for a bright future.

Dean Corliss spoke about his journey from student to dean of GSO, the changes he’s seen at the Narragansett Bay Campus and the future of both the school and oceanography.

Renewing the Bay Campus

[Aboard GSO] You’ve had an opportunity to shape GSO in the past eight years. What was the thought process in the beginning when you sat in that office and looked around: Did you have a plan or did it just start evolving as you got involved?

[Bruce Corliss] One of the charges I had was to look at the campus and try to see if we could improve the business model and operation of the campus. Initially it was just getting up to speed on what was going on here and within the university. A new ship [R/V Resolution]—that was a priority from day one, and something that I knew was going to be very important. The other priority was new faculty. We’ve hired 10 new faculty and are searching for two more. That was something I focused on from the beginning. But there were other things that came along. The NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] Cooperative Institutes, for example, those evolved over time and took seven years to work through with a large group.

What was it like when you came to GSO as dean?

I was a little shocked at the physical condition of the campus. It really was, I thought, in bad shape. There was a lot of deferred maintenance that hadn’t been done because of funding. I don’t think there’d been much pruning of the vegetation for 15 years. It was pretty overgrown.

But the maintenance people were excellent. They stepped up and they started working on the campus.

You speak about the campus and what it looked like, but what about getting people to help with the vision that you had to really elevate this campus?

Over time and conversation, particularly with the Dean’s Advisory Council, we started thinking about the needs of the campus, and in particular, Horn Laboratory. Horn had been on the university’s list for asset protection for a number of years before I got here. This is basically the annual money that comes from the state to maintain and protect university structures. Each year, it would be on the list and then as the year progressed, and money got tighter, it would drop to the bottom of the list.

So, one day [University of Rhode Island] President [David] Dooley was over here for a visit and I said ‘Do you have a couple of minutes?’ I took him over to the Horn lab. Now, he’s a biochemist out of Cal Tech so he’s quite familiar with first-rate laboratory facilities. I just said ‘Here’s the lab that our people are using.’ He was stunned. And at that point, Horn went up to the top of the list and it stayed there.

At some point I concluded we needed a master plan for the entire campus. We could have gone just for Horn replacement, but I thought it would be important to do the whole campus and include Ocean Engineering and the College of the Environment and Life Sciences as well. The key thing was to bring in all the stakeholders and I think as a result of that, we came up with a viable master plan that people have bought into.

Where do you leave that plan now, seven and a half years in?

One of the concerns that we had, in the beginning, was creating a master plan that would just sit on the shelf. But we were able to move it forward with the 2018 state bond—$70 million, of which $45 million goes here to the campus. That’s going to give us a new dock, a new marine operations building, and an ocean technology and robotics center, to be shared between Ocean Engineering and GSO. It really takes that master plan off the shelf and says okay, we’re going to move forward with this and make something happen.

From Student to Dean

We see you running around campus regularly. This is a home for you, isn’t it?

Yes. I was a student here in the ’70s, and so it is important to me for that reason. I’ve come full circle. I’m an outdoorsman, and I enjoy all sorts of outdoor activity, including running. In the middle of the winter I’m out running to get some exercise and to let folks know that I’m still kicking around. [Laughing]

What is it that really made you want to focus your career on the ocean?

I’m a seventh-generation Vermonter and when I was growing up I spent time on Lake Champlain. I went to the University of Vermont and worked on the lake for three summers. I was doing surveys of the lake and studying the sediment distribution. That started my interest in limnology and oceanography. It’s been a long-standing interest that I’ve had since I was quite young.

You were at GSO in the ’70s. What was it like back then?

It was quite different. [Laughing] It was, in comparison to the present, kind of the wild, wild west. There was a larger group of students here—over 100 students at that time. Oceanography was really in a growth phase starting in the ’60s. It was taking off with significant funding from federal agencies and new ships. The work that was being done at GSO was groundbreaking in all sorts of different areas. It was a very exciting time.

Where did you go when you left GSO?

I went to Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution as a post-doc, and then I was on the staff as an assistant and associate scientist. I loved Woods Hole but I thought it would be more attractive to be at a university and to be dealing more with students. So, I left in 1984 and went to Duke. That was the start of a 28-year career at Duke.

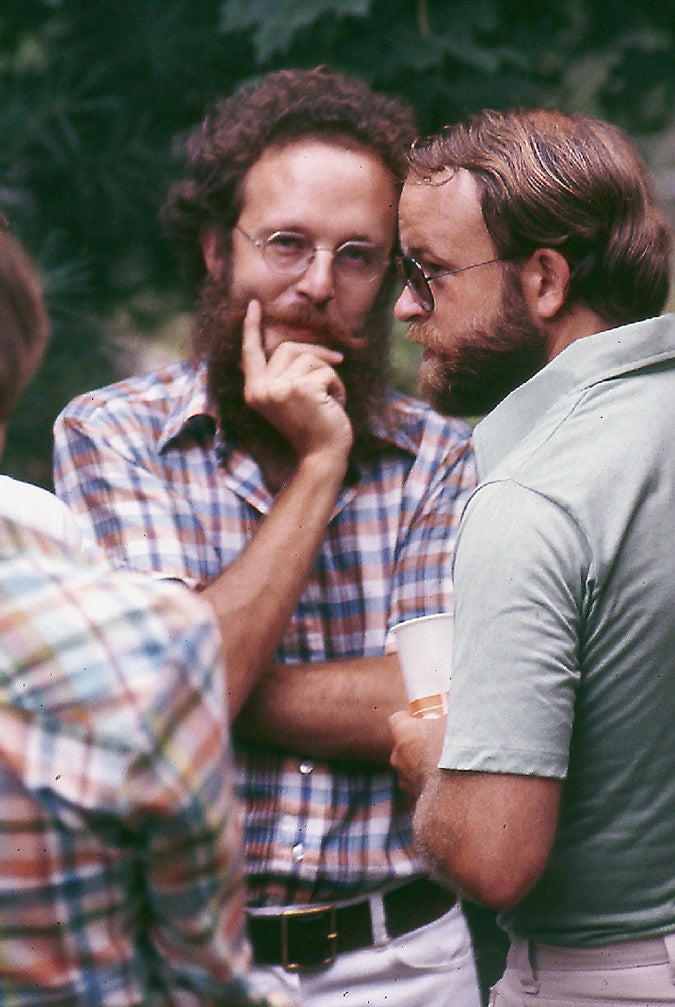

I’m not sure that I thought I would come back to GSO. In the ’70s, John Knauss was here as the founding dean, andhe influenced a number of us—Margaret Leinen [GSO Dean 1991-2000], Jim Yoder [GSO Interim Dean 2000-2001] and I were all in the same class. We were all inspired by Dean John Knauss and the wonderful things he did to create GSO.

Those are some pretty impressive classmates. Do you still keep in touch with them, and what do you talk about?

I’m actually quite close with both of them. Margaret is now director at Scripps [Institution of Oceanography], and Jim has retired as Dean from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and is back here. I see Jim on a weekly basis, and Margaret less frequently but when we get together, we talk about a range of things. They have a really great perspective on GSO and its history and have been very supportive of me and GSO.

You mentioned Margaret Leinen leading Scripps. Tell me how you’ve seen the role of women in science and oceanography change from when you started to now leaving as dean.

Women in the 1960’s at the major institutions broke through a number of barriers to do oceanography and go to sea. For example, Candace Oviatt at GSO and Betty Bunce at WHOI were among those pioneers and I greatly admired them. When I was here in the ’70s, we weren’t really conscious of the inequities because there were women in our class and they were treated as equals. Women were routinely going out on the ship at that time—we just assumed that was part of the overall activity.

Since that time, there’s been an increase in the percentage of women here, as well as in the field. And women now lead some of the oceanographic institutions—Scripps, Bigelow Laboratory, University of Washington and Oregon State University are all led by very impressive and accomplished women. One thing that has been important is that the UNOLS organization [University-National Oceanographic Laboratory System] has given quite a bit of attention over the last five to ten years to issues of equity and harassment at sea. These are issues that we have paid attention to as a community and created a better environment for women at sea.

GSO’s Research Vessel Tradition

When you were at GSO in the ’70s, R/V Trident was here.

It was a converted Army freighter that John Knauss brought over from the Pacific. She was about 180 feet, round bottom. She really rolled. It was quite a different boat from what we have now. I remember having a stateroom just forward of the galley and one could smell a mixture of food and diesel oil that would just waft through the area. It was a different environment as well. Alcohol was allowed on the boats up until seven or eight years ago. It was a much more rough and tough environment—it was a different time.

When you came back as dean, GSO had R/V Endeavor. What are your memories of it?

I was here in 1976 when Endeavor came in and was christened by Mrs. Pell, Senator Clairborne Pell’s wife. I didn’t go out on the Endeavor until 1996 when I was at Duke. I ran five short cruises and had a great experience on the ship. I was impressed with the crew and our present captain [Rhett McMunn] was on some of those cruises at that time.

Tell us about the new ship and why it’s called Resolution.

The new vessel, called a regional class research vessel, will be a very maneuverable vessel that will allow us to do all sorts of things with remotely operated vehicles and autonomous underwater vehicles. She’s being built now and starting to look like a boat—upside down, but nonetheless a boat.

The Endeavor was named by John Knauss, and he had an open competition for people to make suggestions. We did a similar sort of thing. We solicited suggestions from the campus, URI, the state, and from our consortium that we put together with Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, University of New Hampshire, and 13 other institutions. We got over 100 nominations. I put together a large committee and really tried to get a broad representation of faculty, staff, students and others, including representatives from the state. I went for Resolution, which was suggested by four individuals, because it was Captain Cook’s second vessel of exploration, with Endeavour being the first. President Dooley agreed with the recommendation, and so together we made that recommendation to the National Science Foundation. They accepted it, and I’m happy to say that it has been pretty widely appreciated.

Reflecting on the past, looking towards the future

What advice do you have for the new dean coming after you?

It will be an exciting time. The first thing that will come up is continuing the campus renovation. It requires bringing people together, and working out how we’re going to deal with these new buildings. The second thing is continuing faculty development. The people that we’ve hired have been just absolutely first-rate and they’re having, and are going to have, a huge impact, not only on the institution but on the field. I’m really excited about that. And then, just negotiating the ecosystem within the campus, URI and the state. We have had a real team approach, with the university’s support being critical; human resources, communications, the Provost’s office, facilities. That’s very important and it’s based on relationships.

You seem to be someone who tries to bring people together as much as you can. Why do you think that’s so important?

I’ve learned that being inclusive and bringing people in really helps with just about any process. At the end of the day, one person or a few people have to make decisions and you then move forward. But I think one of the essential lessons that any administrator has to learn is that he or she does not have all the best ideas.

The other thing that’s important is determining the objective and staying focused on it. There are many diversions and you have to remember: What’s your objective and how are you going to get there?

Someone who’s influenced me over the last few years is Bob Ballard. We overlapped in graduate school and at Woods Hole, I learned a great deal in terms of how to approach things and have admired him for his creativity, positive attitude and hard work throughout his career. And Jim Kennett, my former Ph.D. advisor, has also had a large influence on me and has been a strong supporter. He inspired an entire generation of paleoceanographers and I have appreciated all of his support.

Tell us how your family has influenced you.

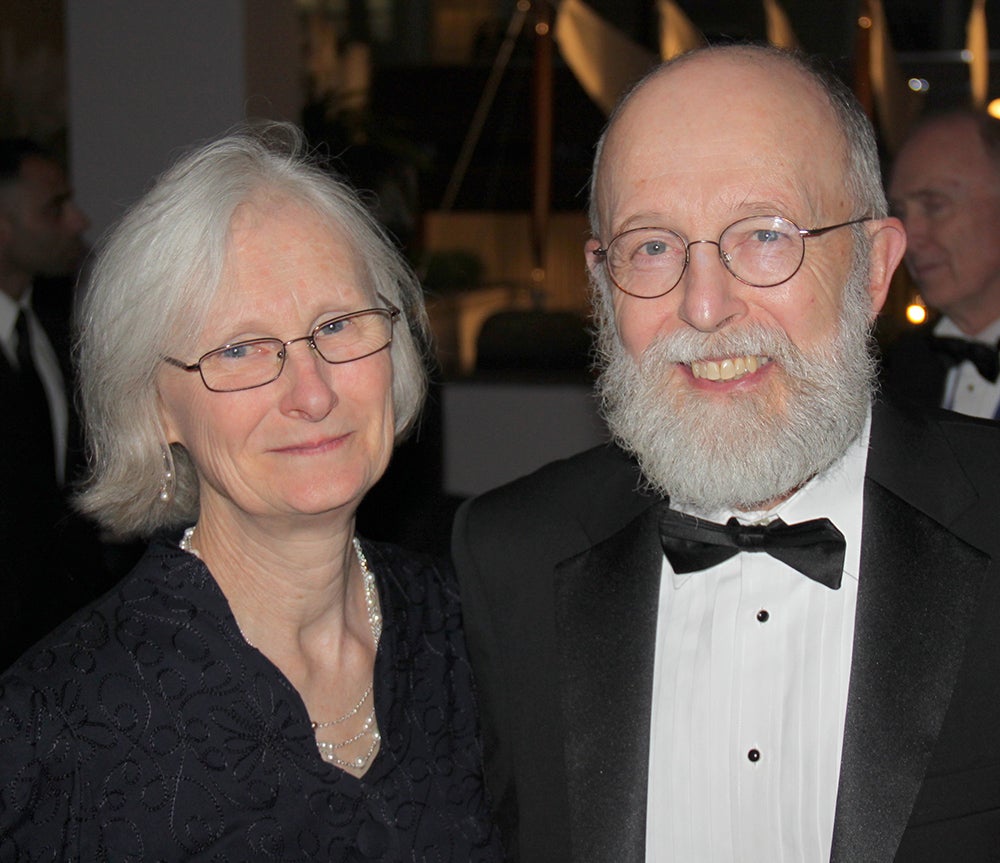

When I was first looking for this job, I was mixed about leaving Duke and coming here. At the time, I was 63 and I was asking is this really a good time to move? My wife, Terry, was very supportive and pointed out, once I took the position, that since I was an alum, I should do what I thought was best for the school. And she has given me a great deal of good advice along the way. I gave my son, Bruce, who just got his Ph.D. in biomedical engineering, all the informa-tion and he said, ‘You know what it’s going to be like at Duke. You’ve been here for a long time, no real surprises at this point. URI is going to be an adventure.’ I went back and thought about it, and three or four days later, I said ‘Okay, I’m going to GSO.’ He started arguing with me. I said ‘I hired you to be the analyst, I didn’t hire you to make the decision.’ [Laughing]

My daughter, Anna, is in fundraising and so she has given me a good perspective. Her feedback was really, really helpful. She was always encouraging me and giving me lecturers on the right way to do things.

Has it been an adventure?

Oh, absolutely. I have enjoyed coming back full circle to GSO: the challenges, the people, Endeavor and Resolution, and developing the master plan for the campus.

Scientist, administrator. The two don’t always work together.

No, there are different skills involved. When I first came here, I thought it was going to be a typical dean position, running a college and worrying about classes and so on. But, that is not the whole story here because oceanography is valued by this state. I was invited to Senator Sheldon Whitehouse’s Providence office within my first two months and Senator Jack Reed was in my office two months later. That was something that I was somewhat surprised by. And, subsequently I’ve had a lot of interaction with, and support from, both of them and their staff, also Congressman Jim Langevin. I think that’s been very important for GSO. I have greatly appreciated Governor Gina Raimondo’s support of GSO as well. I was delighted that she agreed to be the sponsor for the Resolution and will christen the ship when she comes into Narragansett Bay in 2023. My oceanographic colleagues from across the country are envious—we are fortunate to have these leaders in Rhode Island.

What will you miss the most?

I think I’ll miss the big projects, ship activities and the interaction with the people that on a day-to-day basis make up so much of the job.

But you’re not really going anywhere.

I’m going to continue as the principal investigator of the Resolution until she arrives in 2023. I’ll probably sail on Resolution when she comes up from the shipyard. That would be hard to pass up. But otherwise, I’m going to focus on other things.

What do you want to do?

I’m looking forward to fishing on the Narrow River, Ninigret Pond, Woods Hole, and Beaufort Sound in North Carolina.

Any GSO research or discoveries or projects while you were dean that you’re really proud of?

The faculty, staff and graduate students are entrepreneurial and very productive. That has been a tradition since the beginning of GSO and it’s certainly continued. What we do in the Inner Space Center with the concept of telepresence is something that’s really cutting-edge. I think it’s an important part of the future, both for GSO and in oceanography. We’ve rebuilt the Office of Marine Programs, and the Coastal Resources Center has a new director and they’re doing very great things regionally and internationally. I think there’s a variety of things that many people have accomplished that have helped the institution. There are a lot of different parts to it, and the success is due to everybody making contributions in their area. I would include our staff, including the Dean’s Office staff who really make a big difference in their support of GSO and me over the years. I’ve often thought that oceanographic institutions were different because of the capability and attitude of the staff. And I’m even more convinced of that now having spent eight years at GSO. It’s that kind of can-do attitude that you find in oceanographic institutions, such as GSO, that makes them such special places.