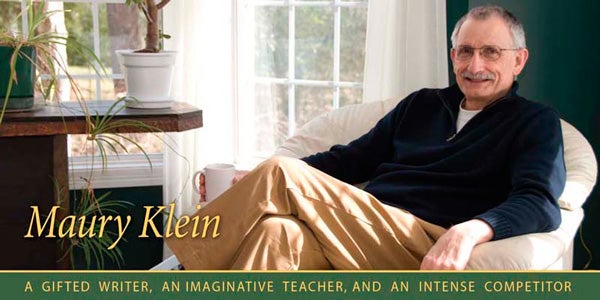

Maury Klein: A Gifted Writer, an Imaginative Teacher, and an Intense Competitor

Nearly 44 years after he began teaching history at the University of Rhode Island, Maury Klein retired at the end of the 2007 fall semester. From teaching, that is. Klein has hardly retired.

The author of 13 books on various aspects of 19th century American history, including three nominated for the Pulitzer Prize, Klein recently finished a large scale book about the steam and electrical revolutions, entitled The Powermakers, which will be published next fall. Another book under contract will follow about the Union Pacific Railroad, about which he has written two volumes. He has a proposal in for a third book, and likely won’t stop after that.

“I’m finally free to write,” Klein says. “It’s what I always wanted to do. I really didn’t know how I would earn a living writing. I figured if I taught history, it’s all there.”

Most of Klein’s students would remember him as an American history scholar and a tough grader. But he is much more than that. An actor who once appeared with the nationally acclaimed Trinity Repertory Company and a persistent athlete, he has balanced the isolation of writing with physically active and interactive “hobbies.”

“I think of Maury as a gifted writer, an imaginative teacher, and an intense competitor,” says History Department colleague Michael Honhart. “I saw Maury’s competitive side when I played softball with him 20 years ago. It doesn’t take much imagination to see the same competitive spirit at work in everything Maury does.”

Klein underwent heart surgery several years ago and works out in a gym three times a week. He still plays softball in the recreation league in South Kingstown in the summers, basketball in a 50-and-over league on Sunday mornings, and pickup games with faculty colleagues twice a week.

“I’ve known Maury for almost 40 years,” says Political Science Professor Alfred Killilea. “The thing about Maury is that he is so witty that he makes the most literary complaints on the court. The referees usually don’t realize he’s complaining.

“When he plays, he has a stigmata about him,” Killilea says half-jokingly. “He sweats on his T-shirt in the shape of Mickey Mouse.”

Good-natured teasing aside, Killilea recalls Klein giving “marvelous lectures” in a summer class he team taught with him on the Watergate scandal in the ’70s. “Students often speak appreciably about Maury’s classes,” Killilea said, “and they must mean it because he is a notoriously hard grader.”

Klein confirms the reputation and complains that since the ’60s and ’70s standards have lagged and student readiness has suffered. “Some of it has to do with the country changing to a visual society over the past 50 years,” he says. “It has destroyed the language and the complexity of ideas that reading and writing allow. As a result, in too many cases, professors give grades to students simply because they did the right thing. I don’t grade as hard as I once did, but I think I grade harder than most.”

Recognized by the University for his teaching and scholarly research, Klein took innovative approaches with several classes including one where a parent of every student in the class also took the course. For another class he invented “The Entrepeneur Game,” where students took the roles of business people, bankers, lawyers, and government officials.

In his early years at URI Klein also devoted himself to institutional activities and committees through the Faculty Senate, but he stopped most of that by the mid-’70s to spend more time writing. The irony of his writing career is that he never intended to become an expert in 19th century history. “I didn’t want to be pigeonholed, so I taught everything I could think of even though I did my Ph.D. dissertation on a Civil War general because I was studying [at Emory University] with a prominent Civil War historian,” he said. “The dissertation became my second book. But most of what I wrote about later was accidental.”

It began to evolve when Klein met a noted historian who suggested he apply for the Newcomen Fellowship at the Harvard Business School. “Surprisingly, I got it, so I spent a year at Harvard, which led to my book on the railroad. After that I got a call from MacMillan asking me to do a volume for a series they were publishing. All of a sudden I was a railroad expert.”

Klein’s knowledge of railroad history and the magnates who drove rail development has attracted national attention. He has appeared in numerous historical documentaries and is often quoted in related works. The Providence Journal, in a recent editorial, referred to Klein as “one of the lesser known treasures of the Ocean State,” citing Klein’s writing about the development of the American economy, a subject that resulted in his best known work, a biography of the financier Jay Gould. The book depicts Gould in a more rounded fashion than as the stereotypical evil, bloodthirsty villain of high finance.

The Life and Legend of Jay Gould became a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. It also inspired Klein to further investigate the “robber barons,” whom he generally describes as extraordinary men who took the risks that built 20th century American economic power. While that is not the popular perception of the likes of Gould, Rockefeller, Carnegie, Harriman, and others, Klein says it is the accurate one.

Along his accidental path, Klein also served for a time as chair of the Theatre Department. Theatre professor Judith Swift, who worked with him on stage and off at URI and off campus, says of him: “Maury is undoubtedly one of the most prolific scholars at URI. I was privileged to work with him on a number of projects. I always found these experiences to be an opportunity to learn a great deal about authenticity and integrity in research.”

Reflecting on his career, Klein sees some irony in having taught at URI for over four decades and having lived in Rhode Island for all of that time. As a child his family moved around the country frequently, and the longest he lived in one place was two-and-a-half years. “I think that’s why I pursued writing, which is a solitary practice,” he said. “But I also needed physical interaction, which is where the athletics come in. I never played on a school team as a kid, but I would miss it now if I didn’t do it.”

He won’t miss his writing; we can expect several more books from the retired professor.

By John Pantalone ’71

Photo By Nora Lewis

Home

Home Browse

Browse Close

Close Events

Events Maps

Maps Email

Email Brightspace

Brightspace eCampus

eCampus